-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

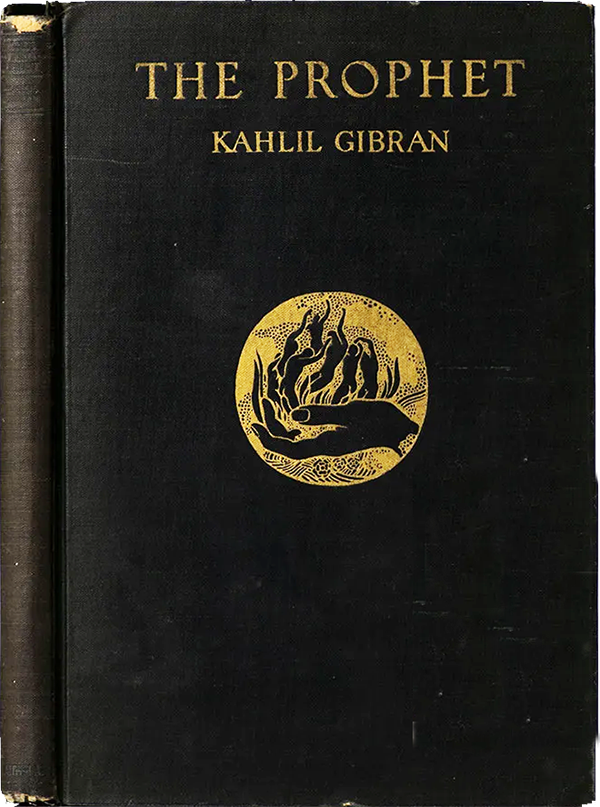

First published in 1923, The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran blends philosophy and mysticism, inspiring millions worldwide with its timeless messages.

Read More

First published in 1923, The Prophet remains a global classic, sharing Gibran’s timeless wisdom on love, life, and the human spirit across generations.

Read More

For over ten years, our small team has lovingly built the world's most comprehensive website —thousands of pages of rare works and discoveries, freely shared.

Now we need your help to sustain it. A modest subscription gives full access while preserving this treasure for future generations.

Subscribe Today - and help us keep Gibran's wisdom alive.