by Philippe Maryssael, retired translator and terminologist.

Arlon, Belgium, 2 November 2019.

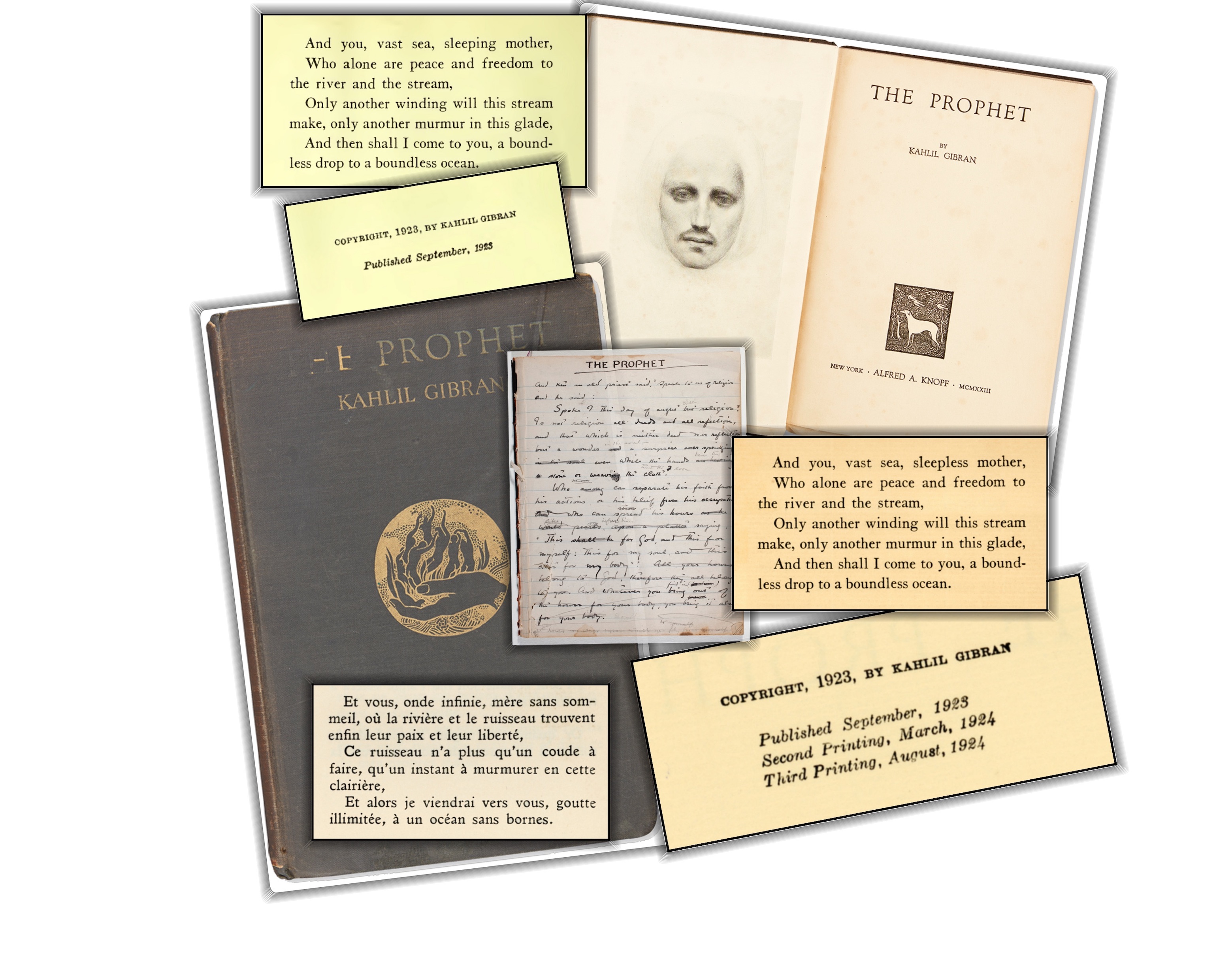

“And you, vast sea, sleeping mother”: a short, six-word sentence at the top of page 10 of the first edition of Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, published in 1923, was later changed to “And you, vast sea, sleepless mother.”

The aim of this paper is to try and provide answers to the following questions: when did the change occur?, why did Kahlil Gibran ask his publisher, Alfred Knopf, to change his text?, and who could have influenced Gibran to change it?

Also considered in this paper is the question of the versions of the text that were used by the men and women who, over time, translated Gibran’s masterpiece into French. Other translation languages are analysed as well, viz. Dutch (and Afrikaans), and Italian.

Keywords - Kahlil Gibran, Prophet, sleeping, sleepless, translation, French, Dutch, Afrikaans, Italian

On 23 September 1923, the New York-based publishing house that was founded in 1915 by Alfred Abraham Knopf and his wife Blanche Knopf published The Prophet, Kahlil Gibran’s third book in English. That book became Gibran’s true masterpiece. In the course of the ninety-five years between September 1923 and the end of 2018, Knopf (and subsequently the Penguin Random publishing house that acquired Knopf’s publishing house in 1960) released no fewer than 188 uninterrupted printings of the book. According to some sources, a mere 1,159 copies of The Prophet sold in the first year. Sales would then double with every subsequent year, eventually reaching the 240,000 mark in 1965. The Prophet became one of Knopf’s most successful books1, with total sales figures for the English book estimated at over ten million copies in the United States alone.

Working together for several years, Francesco Medici, a renowned Italianist who translated several of Gibran’s works into Italian, including Il Profeta in 2005, and Glen Kalem, an Australian filmmaker and Kahlil Gibran scholar who enthusiastically maintains the Kahlil Gibran Collective website2, have irrefutably established that, to this day, Gibran’s masterpiece received no fewer than one hundred eleven translations in different languages and/or countries of the world ever since it was first published3. On 1 January 2019, after ninety-five years of copyright protection under United States law, the text of The Prophet eventually entered the public domain4. The number of publications of the book in English has since been rocketing skywards, with more and more translations being identified on a regular basis.

But, way back on 23 September 1923, Kahlil Gibran held in his hands the first copy of his third book in English and, a few days later, on 2 October, Mary Haskell, Gibran’s closest friend and benefactress, who meticulously helped him to correct and improve his text, received by post her own copy that Gibran had sent her. On that very day, as quoted in Virginia Hilu’s book Beloved Prophet, Mary Haskell wrote Kahlil Gibran the following letter:

Clarkesville, Georgia October 2, 1923

Beloved Kahlil,

The Prophet came today, and it did more than realize my hopes. For it seemed in its compacted form to open further new doors of desire and imagination in me, and to create about itself the universe in nimbus, so that I read it as at the centre of all things. The format is excellent, and lets the ideas and the verse flow quite unhampered. The pictures make my heart jump when I see them. They are beautifully done. I like the book altogether in style.

And the text is more beautiful, nearer, more revealing, more marvellous in conveying Reality and in sweetening consciousness—than ever. The English, the style, the wording, the music—is exquisite, Kahlil—just sheerly beautiful. Bless you, bless you, bless you, for saying it all, and for being such a worker that you bring that inner life into form and expression—for having the energy and the patience of fire and air and water and rock.

This book will be held as one of the treasures of English literature. And in our darkness we will open it to find ourselves again and the heaven and earth within ourselves. Generations will not exhaust it, but instead, generation after generation will find in the book what they would fain be—and it will be better loved as men grow riper and riper.

It is the most loving book ever written. And it is because you are the greatest lover, who ever wrote. But you know, Kahlil, that the same thing happens finally, whether a tree is burned up in flame, or falls silently in the woods. That flame of life in you is met by the multiplied lesser warmth of the many many who care for you. And you are starting a conflagration! More will love you as years go by, long long after your body is dust. They will find you in your work. For you are in it as visibly as God is.

Goodbye, and God bless you most dearly, beloved Kahlil, and sing through your mouth more and more of his songs and yours.

Love from Mary5

In Gibran’s lifetime, as many as twenty-five printings of The Prophet were published by Knopf:

1. Published 23 September 1923

2. Second Printing, March 1924

3. Third Printing, August 1924

4. Fourth Printing, January 1925

5. Fifth Printing, May 1925

6. Sixth Printing, September 1925

7. Seventh Printing, December 1925

8. Eighth Printing, February 1926

9. Ninth Printing, October 1926

10. Tenth Printing, December 1926

11. Eleventh Printing, April 1927

12. Twelfth Printing, July 1927

13. Thirteenth Printing, December 1927

14. Fourteenth Printing, January 1928

15. Fifteenth Printing, March 1928

16. Sixteenth Printing, October 1928

17. Seventeenth Printing, December 1928

18. Eighteenth Printing, February 1929

19. Nineteenth Printing, July 1929

20.Twentieth Printing, September 1929

21.Twenty-first Printing, December 1929

22.Twenty-second Printing, March 1930

23.Twenty-third Printing, July 1930

24.Twenty-fourth Printing, October 1930

25. Twenty-fifth Printing, February 1931

26. Twenty-sixth Printing, October 1931 (first posthumous printing)

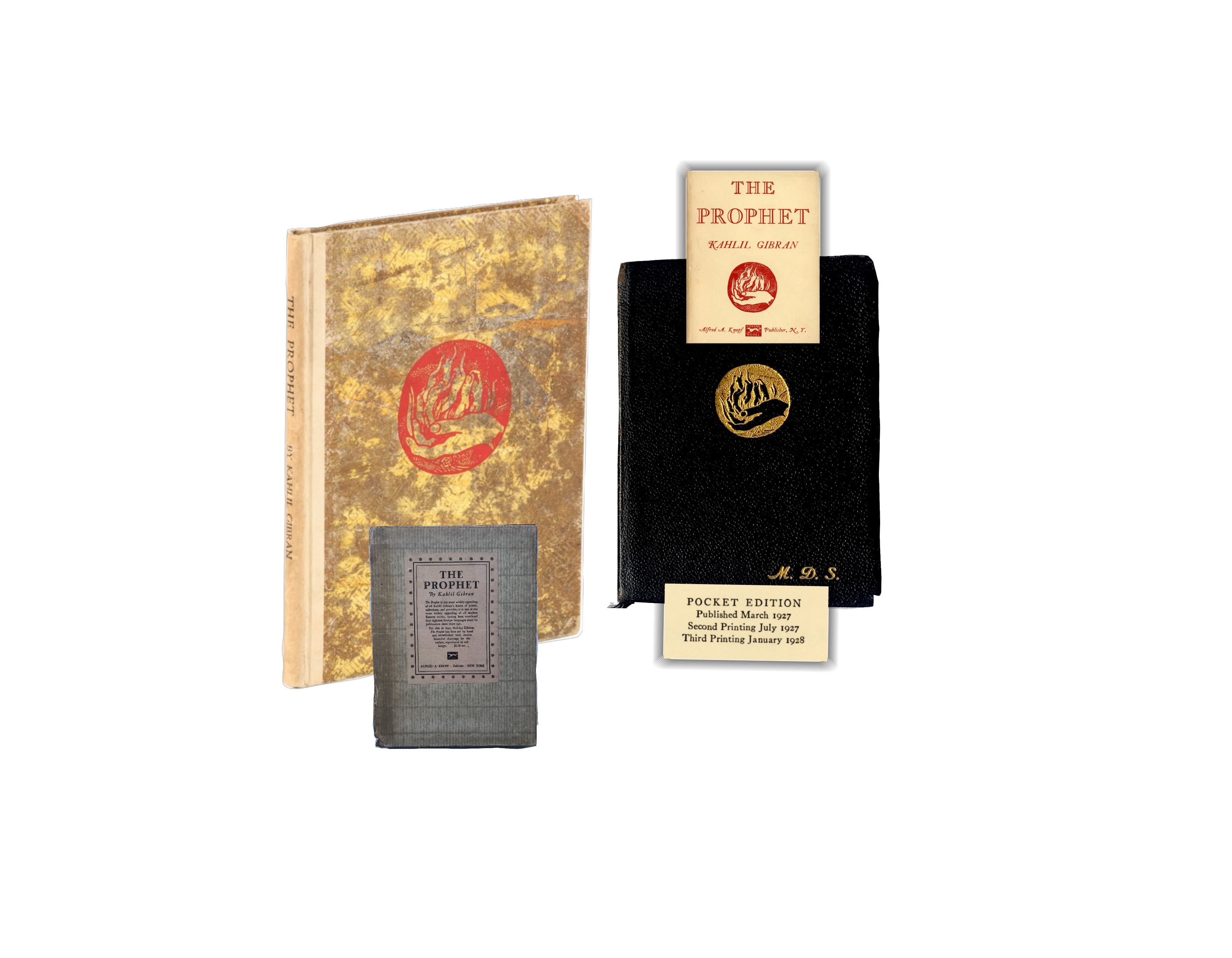

In addition to the book’s standard edition (15.5 cm x 22 cm), Knopf also published two other formats: a special, holiday deluxe edition in a slipcase (21 cm x 27.5 cm) and a pocket edition (11.5 cm x 14.5 cm).

Of the deluxe edition, only one printing was published in Gibran’s lifetime. It was in November 1926, the second dating posthumously from October 1938. Of the pocket edition, seven printings were published in Gibran’s lifetime, namely:

Of the deluxe edition, only one printing was published in Gibran’s lifetime. It was in November 1926, the second dating posthumously from October 1938. Of the pocket edition, seven printings were published in Gibran’s lifetime, namely:

1. First published March 1927

2. Second Printing, July 1927

3. Third Printing, January 1928

4. Fourth Printing, September 1928

5. Fifth Printing, July 1929

6. Sixth Printing, January 1930

7. Seventh Printing, September 1930

8. Eighth Printing, July 1931 (first posthumous printing)

As far as early translations are concerned, the very first foreign-language version of The Prophet was published in Munich, Germany, in 1925, under the German title Der Prophet, translated by Baron Georg-Eduard von Stietencron (1888-1974). Only 800 numbered copies of his translation are known to have been printed.6

In 1926, two other translations were published, first in Arabic by a young clergyman, the Lebanese-born Antonios Bashir7 (1889-1966), who later became the Orthodox Archbishop of New York and the Metropolitan of All North America, the ruling bishop of the North American archdiocese of the Church of Antioch. His translation, under the title al-Nabī, was published in Cairo.8

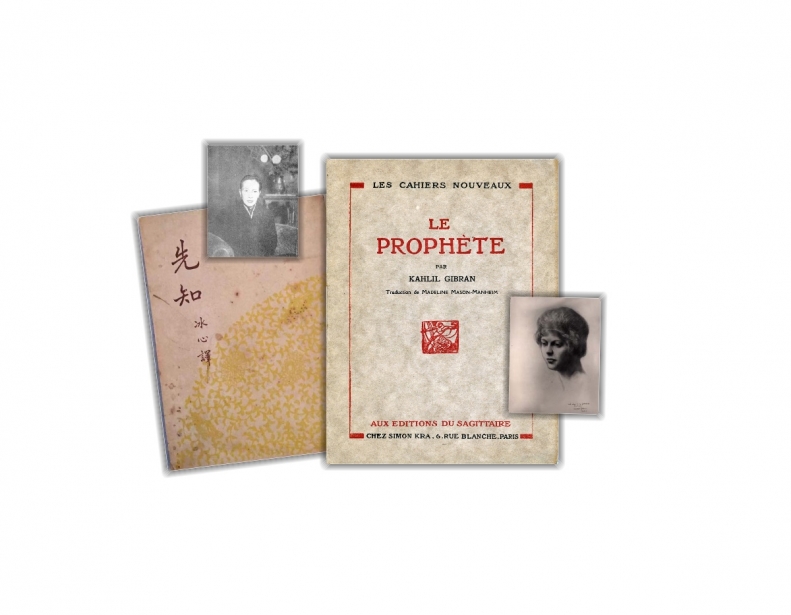

The other translation that was published that same year was in French, under the title Le Prophète. The book was translated by a young, then 18-year old, American poet named Madeline Mason (1908-1990). Only 750 numbered copies of Le Prophète were printed, of which 25 copies on Japon paper (from no. 1 to no. 25) and 725 on Vélin de Rives paper (from no. 26 to no. 750). Madeline Mason spent much of her childhood and teenage years in England and France where her parents had homes, hence her excellent command of the French language. In the early 1920s, Gibran drew a pencil portrait of her, and they became close friends. One year before Le Prophète was published in Paris, Madeline Mason had her first collection of poems published in London under the title Hill Fragments, with reproductions of five drawings by Gibran.9

The fourth translation of The Prophet to have ever been published was the Dutch version. Under the title De Profeet, it came out in The Hague, The Netherlands, in 1927. The translator was Liesbeth Christina Valckenier-Suringar (1901-1956), a social worker and teacher from Amsterdam.10

Later came the translations in Yiddish as Der novi by Isaac Horowitz in 1929, in Chinese as Xiānzhī by Bing Xin in 1931, and in Italian as Il Profeta by Eirene Niosi-Risos (a.k.a. Antonia Irene Risos) in 1936.11

From the first printing of The Prophet up to the third, the latter being part of our personal collection, the short sentence at the top of page 10 reads as follows: “And you, vast sea, sleeping mother.” To our surprise, when we acquired the 12th printing, we came upon the same sentence and realised that it was not quite the same sentence indeed: “And you, vast sea, sleeping mother” had become “And you, vast sea, sleepless mother.” The first deluxe edition of November 1926 and the first pocket edition of March 1927 both contain the updated sentence.

So, betwixt August 1924 (3rd printing of the standard edition) and November 1926 (deluxe edition), something had happened that made Gibran want to change that very sentence. Madeline Mason’s Le Prophète (1926) contains the following translation: “Et vous, onde infinie, mère sans sommeil” (literally: “And you, boundless waters, sleepless mother”). Considering that Madeline and Gibran were close friends, and that he was proficient in French12, we may assume with a fairly high degree of certainty that the two of them reviewed her French translation together. Most probably, Madeline translated The Prophet in the course of 1924 and 1925, during the same period her collection of poems was completed and prepared for publication. At that time, she must have interacted closely with Gibran for the selection of the drawings that he let her use as illustrations in Hill Fragments.

So, betwixt August 1924 (3rd printing of the standard edition) and November 1926 (deluxe edition), something had happened that made Gibran want to change that very sentence. Madeline Mason’s Le Prophète (1926) contains the following translation: “Et vous, onde infinie, mère sans sommeil” (literally: “And you, boundless waters, sleepless mother”). Considering that Madeline and Gibran were close friends, and that he was proficient in French12, we may assume with a fairly high degree of certainty that the two of them reviewed her French translation together. Most probably, Madeline translated The Prophet in the course of 1924 and 1925, during the same period her collection of poems was completed and prepared for publication. At that time, she must have interacted closely with Gibran for the selection of the drawings that he let her use as illustrations in Hill Fragments.

Could it be that one of Madeline’s poems from Hill Fragments triggered in Gibran’s mind the change from “sleeping mother” to “sleepless mother”? That is a hypothesis that we believe to be highly plausible. Unfortunately, it cannot be confirmed because neither of the protagonists is alive today. From Hill Fragments, one poem is titled “The Ocean”. It clearly refers to the restlessness, or sleeplessness, of the ocean, or sea, that knows no pause...

THE OCEAN

O thou restless one,

What mighty urge is in thy bosom

That nor night nor day

Thy striving knoweth pause?

Thou toilest ever to outreach thy bounds; Thou movest onward,

Though the shroud of Night

Lie heavy on thy breast;

And in the golden sun

Thou leapest merrily

To distant goals.

Earth fain would stay thee.

0, thou art merciless:

Thou woundest her

Until the bonds are rent

That hold thee.

And yet thou lovest her well.

But in thy longing for thine own fulfilment Is thy passion,

And though thou bringest treasures

And with tender sighing

Layest them before her,

Yet art thou ever distant,

Lonely, unapproachable.

0 thou restless one,

What mighty urge is in thy bosom

As down the timeless aisles of Space

Thou criest evermore: “Beyond! Beyond!”13

We recently managed to acquire the 4th printing of the standard edition, and the sentence at the top of page 10 reads: “And you, vast sea, sleepless mother”. We can now narrow down the period of time during which Gibran decided on the change: between August 1924 (3rd printing) and January 1925 (4th printing), i.e. during the second half of the year 1924, one year after the publication of the first edition (September 1923).

In Gibran’s body of writings, we have managed to identify two texts that refer to the restless or sleepless sea. The first, titled “Revelation”, is from the collection of poems, under the title Prose Poems, that was published by Knopf in 1934, with a foreword by Barbara Young. It was translated from the Arabic by Andrew Ghareeb. The Arabic version of the poem first appeared in Al-Funoon in March 1916, whilst its English version appeared for the first time in the Syrian World in June 1931.

REVELATION

When the night waxed deep and slumber cast its cloak upon the face of the earth,

I left my bed and sought the sea, saying to myself:

"The sea never sleeps, and the wakefulness of the sea brings comfort to a sleepless soul."

When I reached the shore, the mist had already descended from the mountain tops

And covered the world as a veil adorns the face of a maiden.

There I stood gazing at the waves, listening to their singing, and considering the power that lies behind them—

The power that travels with the storm, and rages with the volcano, that smiles with smiling flowers and makes melody with murmuring brooks.

After a while I turned, and lo,

I beheld three figures sitting upon a rock near by,

And I saw that the mist veiled them, and yet it veiled them not.

Slowly I walked toward the rock whereon they sat, drawn by some power which I know not.

A few paces off I stood and gazed upon them, for there was magic in the place

Which crystallized my purpose and bestirred my fancy.

And at that moment one of the three arose, and with a voice that seemed to come from the sea depths he said:

“Life without love is like a tree without blossoms or fruit.

And love without beauty is like flowers without fragrance, and fruit without seeds.

Life, Love, and Beauty are three entities in one self, free and boundless,

Which know neither change nor separation.”

This he said, and sat again in his place.

Then the second figure arose, and with a voice like the roar of rushing waters he said:

“Life without rebellion is like the seasons without a spring.

And rebellion without right is like spring in an arid and barren desert.

Life, Rebellion, and Right are three entities in one self,

And in them is neither change nor separation.”

This he said, and sat again in his place.

Then the third figure arose, and spoke with a voice like the peal of the thunder, saying:

“Life without freedom is like a body without a spirit.

And freedom without thought is like a spirit confounded.

Life, Freedom, and Thought are three entities in one eternal self,

Which neither vanish nor pass away.”

Then the three arose and with voices of majesty and awe they spoke:

“Love and all that it begets,

Rebellion and all that it creates,

Freedom and all that it generates,

These three are aspects of God...

And God is the infinite mind of the finite and conscious world.”

Then silence followed, filled with the stirring of invisible wings and the tremor of the ethereal bodies.

And I closed my eyes, listening to the echo of the saying which I heard.

When I opened my eyes, I beheld naught but the sea hidden beneath a blanket of mist;

And I moved closer toward that rock

And I beheld naught but a pillar of incense rising unto the sky.14

The second text in which Gibran wrote of the restless sea is his epic poem The Earth Gods, which was published on 14 March 1931, just a few weeks before he passed away on 10 April.

THE EARTH GODS

When the night of the twelfth æon fell,

And silence, the high tide of the night, swallowed the hills,

The three earth-born gods, the Master Titans of life,

Appeared upon the mountains.

Rivers ran about their feet;

The mist floated across their breasts,

And their heads rose in majesty above the world.

Then they spoke, and like distant thunder

Their voices rolled over the plains.

(...)

FIRST GOD

Weary is my spirit of all there is.

I would not move a hand to create a world

Nor to erase one.

I would not live could I but die,

For the weight of æons is upon me,

And the ceaseless moan of the seas exhausts my sleep.

Could I but lose the primal aim

And vanish like a wasted sun;

Could I but strip my divinity of its purpose

And breathe my immortality into space,

And be no more;

Could I but be consumed and pass from time’s memory

Into the emptiness of nowhere!15

Confusion also arose from the fact that the British publisher of The Prophet, the London-based William Heinemann Ltd publishing house, failed to align their publications with the version of Gibran’s masterpiece that was published in New York. Indeed, they first published The Prophet in January 1926, one full year after Knopf published the 4th printing of the book with the updated sentence. The Heinemann version contained the original sentence “And you, vast sea, sleeping mother”. The text has remained unchanged until recently: suffice it to consult their 8th printing of November 1935 and their 23rd printing of 1962, and the Penguin Books paperback edition of 1992.

The situation regarding the change eventually got clarified once and for all in the ultimate, world-wide edition of 2019 by Penguin Books, which includes a foreword by Rupi Kaur, an Indian-born Canadian poetess, visual artist and illustrator. At last, at long last, the sea-mother has forevermore become sleepless.

Forevermore? Well, not exactly... In 2011, Macmillan Collector’s Library (Pan Macmillan) published a gilt-edged pocket-size version of The Prophet that contains the original, first-edition sentence. And in early 2019, a lavish, leather-clad, slipcase-protected deluxe edition of The Prophet with exquisite, high-quality coloured reproductions of Gibran’s original drawings and paintings was published by the London-based publishing house The Folio Society Ltd, also reproducing the text in its original version, thus keeping the sentence “And you, vast sea, sleeping mother”.

By comparing numerous translations of The Prophet into French, Dutch (and Afrikaans, a South-African language very close to Dutch), and Italian, we have identified that the translators used either the original version of the text or the updated version as their references while rendering the book in their respective languages.

Twenty-three French translations of The Prophet have been consulted. They are presented chronologically:

For the Dutch and Afrikaans languages, the following editions have been consulted:

For the Italian language, the editions at our disposal are the following:

We have established without any possible doubt that the original text at the top of page 10 of The Prophet, as it was published for the first time in New York on 23 September 1923, was changed from “And you, vast sea, sleeping mother” to “And you, vast sea, sleepless mother” from the 4th printing of January 1925 onwards. We have also identified that, contrary to the updated American version, the British version of the text was not updated until fairly recently.

Based on our investigation into the versions, it can be established that the definitive version of Gibran’s masterpiece should be the one with the updated sentence “And you, vast sea, sleepless mother,” and this, irrespective of the fact that recent editions by other publishing houses than Knopf or Heinemann, or the ones that bought them up, contain the original, non-updated version.

It can be assumed fairly reasonably, although it cannot be proven with absolute certainty, that, in the course of their interactions within the scope of Madeline Mason and Kahlil Gibran reviewing the former’s translation of The Prophet into French on the one hand, and within the scope of the selection of Kahlil Gibran’s drawings used as illustrations for Madeline Mason’s Hill Fragments on the other hand, the change from “sleeping mother” to “sleepless mothers” may have been influenced by a poem from Hill Fragments. However, two texts from Gibran’s body of works refer to the sea being restless, sleepless or ceaseless in it moaning. One of the two identified texts dates back from years before the publication of The Prophet, at least in the original Arabic language, whilst the other was published at a later date.

As for the consulted translations of the text into French, Dutch (and Afrikaans), and Italian, the translators used either the original American version, or the updated American version, or—probably for some of them—the non-updated British version.

Looking into the future, further research could be conducted internationally, on a much larger scale, with a view to identifying, for all available translations of The Prophet, the versions upon which the translators based their translations.

Philippe Maryssael was born in Brussels, Belgium, in 1962. He studied translation in Brussels in the early 1980s. He later studied terminology and terminotics, the set of techniques involving the use of computer software in conducting terminology research on vast text corpora and deploying terminology database and translation memory solutions in support of the translation business.

His first job was as a bank clerk in Brussels. After a couple of years, he became a professional translator and terminology pioneer in the insurance and financial sectors before he moved to Luxembourg and joined a European financial institution as a translator-reviser, terminologist and computer-aided translation and terminology tools specialist. There, after a decade, he changed the course of his career and became a business process manager involved in paving the way to the institution-wide dissemination of business process optimisation and re-engineering practices.

In July 2017, he decided to retire. The time was right for him to indulge in his life-long interest in the writings of Kahlil Gibran. He started collecting first editions of the books that Gibran wrote in English. He also started comparing the numerous French translations of his works. The natural next step was his intention to provide personal translations of Gibran’s English books into French and to have them published. His first published work came out at the end of 2018: The Fol, a bilingual presentation of the text of The Madman and his new translation, with an in-depth analysis of Gibran’s use of the English language and a study of several themes across his entire body of books.

More information on Philippe Maryssael and his translation projects can be found on his personal website at http://www.maryssael.eu/en/.

1 More detailed information about the Knopf publishing house can be found on the Wikipedia website at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_A._Knopf.

2 Founded, supported and managed by dedicated researchers, scholars and biographers of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell, the KGC’s aim is to further the scholarship of Kahlil Gibran’s life, work and legacy. KGC members will partake in active international programs, events and publications that will further this cause, and in the foreseeable future create forums, such as conferences, speakers programs and film. The site will also serve as a unique and important resource for researchers, admirers and scholars of Gibran, with regular news and media announcements, including online publications from various global institutes concerning essays judged to be of interest. The KGC has also made available for the first time the complete Digital Archive of Kahlil Gibran’s literary works. The scope of Gibran’s studies is vast, ranging from topics related to the dialogue of civilizations, interfaith reconciliation, human rights, environmental sustainability, and the spiritual and ethical foundations for a global society. As Gibran’s work increases in influence in the world and continues being translated into new languages such as Hindi, Chinese, and Papiamentu, the KGC will aim at highlighting and celebrating those findings. The Kahlil Gibran Collective website can be visited at https://www.kahlilgibran.com/.

3 KALEM Glen, The Prophet Translated, The Kahlil Gibran Collective, 2019 (https://www.kahlilgibran.com/29- the-prophet-translated-2.html) and subsequent articles

4 KALEM Glen, End of the Copyright Road for The Prophet, The Kahlil Gibran Collective, 2019 (https://www.kahlilgibran.com/45-the-prophet-enters-the-public-domain.html)

5 HILU Virginia, Beloved Prophet, pages 416-417

6 MEDICI Francesco, Gibran’s The Prophet in All the Languages of the World, speech at the 5th International Gibran Conference that took place at the Arab World Institute in Paris on 3 October 2019

7 Information on Antonios Bashir can be found on the OrthodoxWiki website, a free-content encyclopaedia and information centre for Orthodox Christianity, at https://orthodoxwiki.org/Anthony_(Bashir)_of_New_York.

8 MEDICI Francesco, Gibran’s The Prophet in All the Languages of the World 9 Ibidem.

10 Ibidem.

11 Ibidem.

12 We know for a fact that Gibran learnt French at Collège de la Sagesse (currently the Sagesse University — http://www.uls.edu.lb/) in Beirut. Between 20 October 1989 and 13 July 1901, he studied there, perfecting his command of the Arabic language, learning French and discovering Arabic poets and thinkers, as well as Sufism. He was awarded a first prize in poetry. (based on NAJJAR Alexandre et alii, Œuvres complètes, page 921 and NAJJAR Alexandre, Gibran, pages 56-61)

13 MASON-MANHEIM Madeline, Hill Fragments, page 14

14 GIBRAN Kahlil, Prose Poems, pages 12-15

15 GIBRAN Kahlil, The Earth Gods, pages 3 & 5-6

GIBRAN Kahlil, The Prophet, The Folio Society Ltd, London, 2019 (leather-clad deluxe edition in slipcase), vii & 99 pages

GIBRAN Kahlil, The Prophet, William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1926 (8th printing of November 1935), 118 pages

GIBRAN Kahlil, The Prophet, William Heinemann Ltd, London, 1926 (23rd printing of 1962), 118 pages

GIBRAN Khalil, Il Profeta (translation of 2015 by Andrea Montemagni), Edizioni Clandestine, Lavis (Trento), 2017, 94 pages, ISBN 978-88-6596-645-7

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (traduction de 1993 par Jean-Pierre Dahdah), Éditions du Rocher (Alphée), Paris, 1993 (2005), 208 pages, ISBN 978-2-7538-0037-5

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation de 1990 by Marc de Smedt), Éditions Albin Michel, Paris, 2004, 143 pages, ISBN 978-2-226-03922-8

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 1956 by Camille Aboussouan), Éditions Casterman, Tournai, 1977 (hardcover edition on Van Gelder Zonen watermarked paper), 105 pages, ISBN 2-203-23140-8

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 1982 by Antoine Ghattas Karam), Éditions Actes Sud, Paris, 1991, 105 pages, ISBN 2-7274-0201-5

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 1985 by Michaël la Chance), Éditions Athena / Idégraf, Suisse, 1985, 92 pages

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 1992 by Anne Wade Minkowski), Éditions Gallimard, Paris, 2003, 111 pages, ISBN 978-2-07-038480-2

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 1992 by Salah Stétié) in Œuvres complètes, Éditions Robert Laffont, Paris, 2006 (reprinted in 2014), 953 pages, ISBN 978-2-221-10503-0

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 1994 by Guillaume Villeneuve) followed by Le Jardin du Prophète and Le Sable et l’Écume, Éditions du Chêne, Paris, 2010, 287 pages, ISBN 978-2-81230-176-6

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 1998 by Salah Stétié, drawings by Gabriel Lefebvre), Éditions La Renaissance du Livre (Collection Littérature illustrée), Bruxelles, 2008, 117 pages, ISBN 978-2-5070-0009-7

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 1999 by Bernard Dubant, with an introduction and annotations by Suhell Bushrui), Guy Trédaniel Éditeur, Paris, 1999, 59pages, ISBN 2-84445-115-2

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 1999 by Cécile Brunet-Mansour et Rania Mansour) in Enfants du Prophète : Œuvre anglaise, Éditions Al-Bouraq, Beyrouth, 1999, 735 pages, ISBN 2-84161-062-4

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 2006 by Pierre Ripert), Éditions de la Seine, Paris, 2006, 59 pages, ISBN 978-2-743-45806-5

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 2008 by Jean-Christophe Benoist), Bibliowiki, s.l., s.d. (https://biblio.wiki/wiki/Le_Prophète)

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 2008 by Nicola Hahn, with Mīkhā’īl Nu‘aymah’s Arabic translation), Éditions Bachari, Paris, 2008, 127 pages, ISBN 978-2-913678-50-7

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 2010 by Philippe Morgaut), Éditions Marabout, Paris, 2010, 91 pages, ISBN 978-2-501-06552-8

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 2012 by Didier Sénécal), Éditions Pocket, Paris, 2014, 94 pages, ISBN 978-2-266-22329-4

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète (translation of 2016 by Philippe Morgaut), Éditions Marabout, Paris, 2016, 143 pages, ISBN 978-2-501-10991-8

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète, (translation of 1983 by Paul Kinnet), Les Éditions de la Mortagne, Boucherville (Québec), 1994, 108 pages, ISBN 978-2-89074-055-2

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète, (translation of 1993 by Janine Lévy) Librairie Générale de France / Éditions du Chêne, Paris, 1997, 99 pages, ISBN 978-2-851-08834-5

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète, (translation of 2008 by Omayma Arnouk el-Ayoubi), Éditions Érick Bonnier, Paris, 2015, 91 pages, ISBN 978-2-3676-0032-1

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète, (translation of 2012 by Salah Stétié), Naufal, Beyrouth, 2012, 159 pages, ISBN 978-9953-26-188-1

GIBRAN Khalil, Le Prophète, Le Jardin du Prophète, La Mort du Prophète (translation of 2013 by Anne Juni, with calligraphies by Mohammed Idali), Éditions La Part Commune, Rennes, 2013, 204 pages, ISBN 978-2-84418-258-6

GIBRAN Khalil, Œuvres complètes (presented by Alexandre Najjar), Éditions Robert Laffont, Paris, 2006 (reprinted in 2014), 953 pages, ISBN 978-2-221-10503-0

HILU Virginia, Beloved Prophet — The Love Letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell and her Private Journal, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1972 (fourth printing, November 1974), 450 pages, ISBN 0-394-43298-3

MASON-MANHEIM Madeline, Hill Fragments, Cecil Palmer, London, 1925 (1st edition), xvi & 59 pages

NAJJAR Alexandre, Gibran, L’Orient des Livres, Beyrouth, 2012, 235 pages, ISBN 978-9953-0-2550-6