by Francesco Medici

All rights Reserved © Francesco Medici

“Speak to us of Beauty”...

...is the simple exhortation used by an anonymous poet to address Almustafa, the main character in the celebrated poème en prose by Kahlil Gibran titled The Prophet. What is beauty? It is said that at one time the same question was asked to the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, who answered: “I have always been charmed and possessed by it. I have often attempted to use words to communicate what beauty is, yet I have always failed. Beauty is an experience that cannot be expressed.”

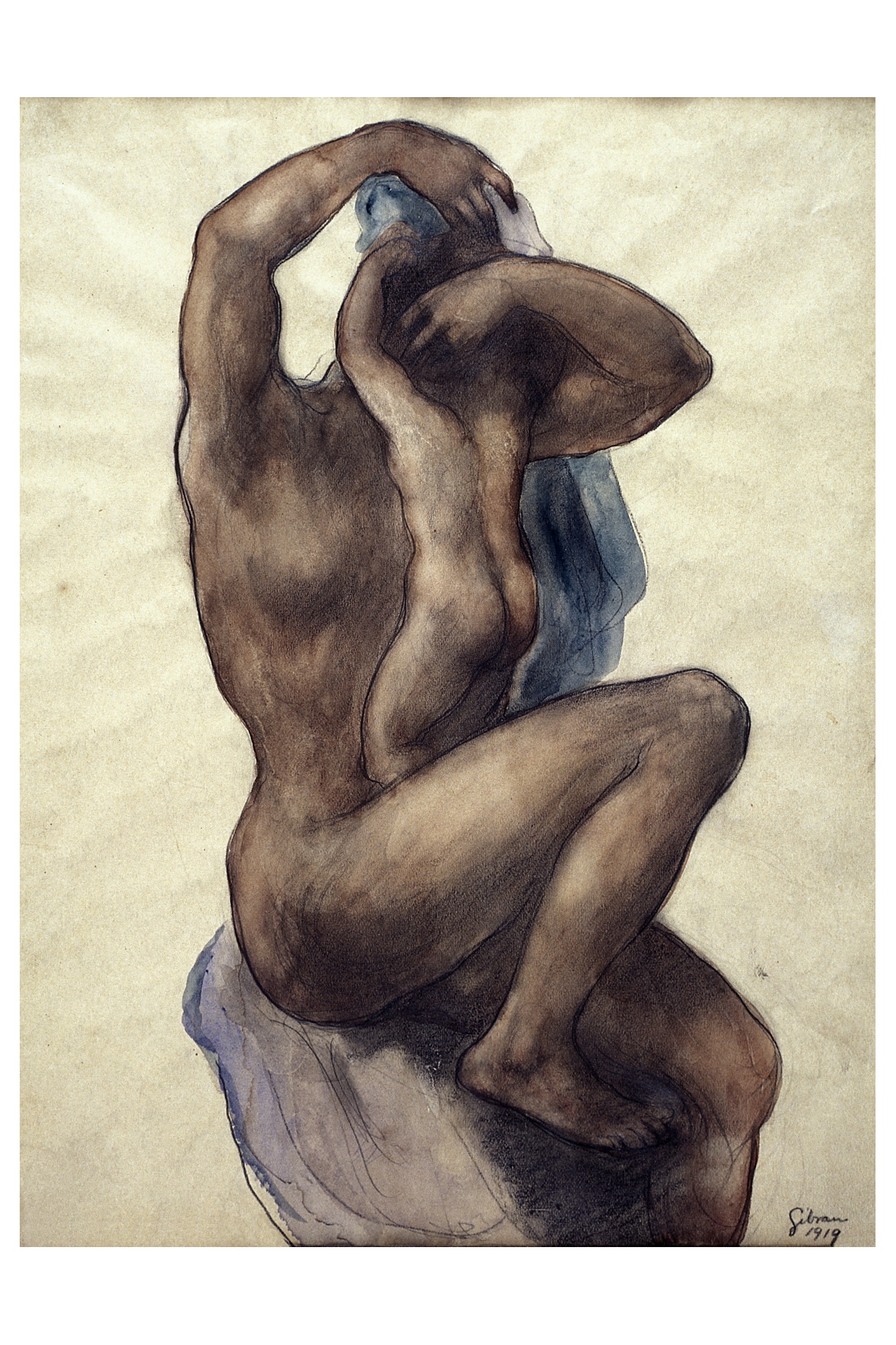

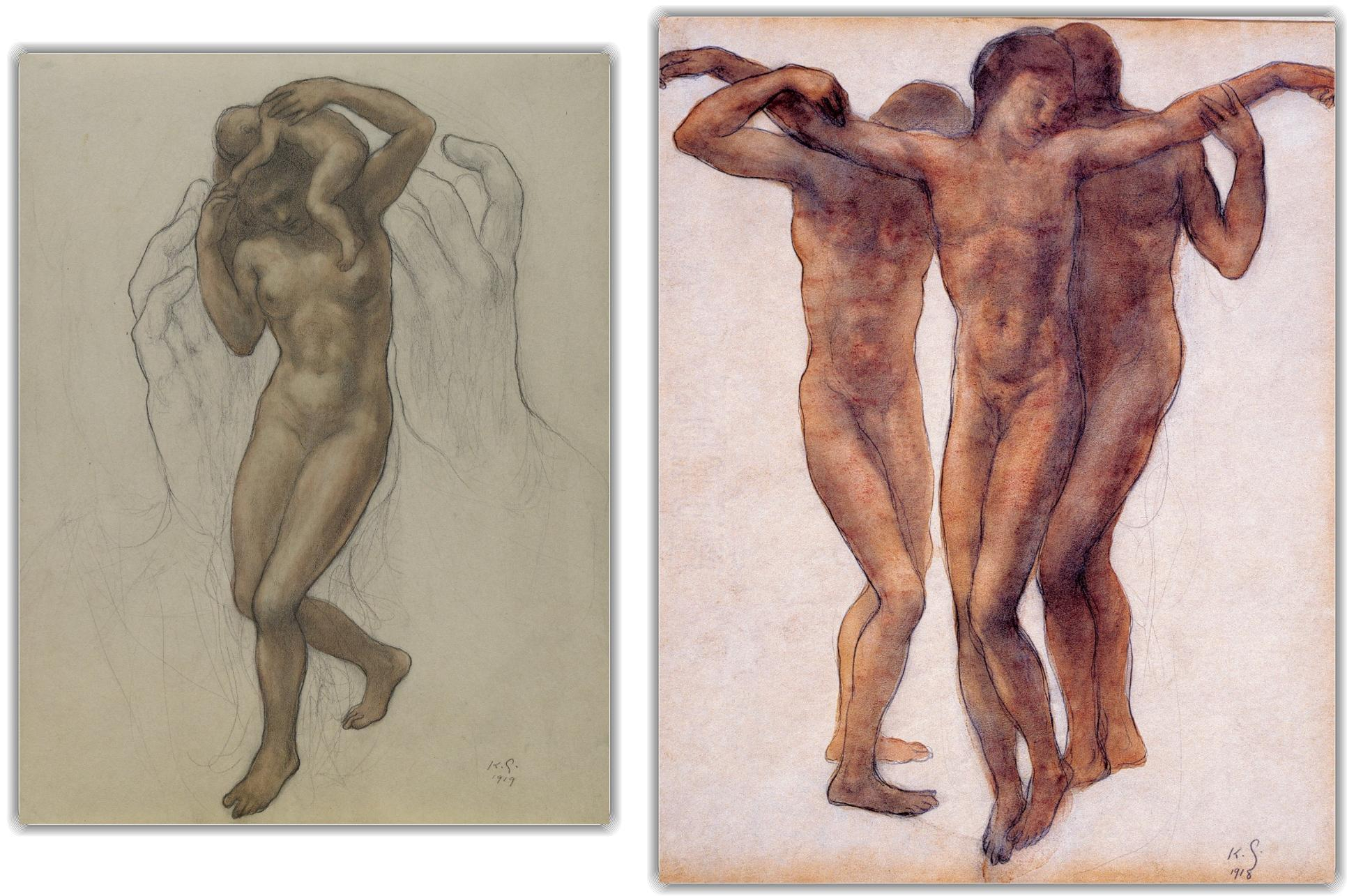

When, in 1919, Twenty Drawings appeared in bookshops in New York, Gibran’s devoted readers were disoriented by it, and the critics’ comments were lukewarm. Although the original editions of his literary works were all embellished by splendid illustrations, this was the first volume published during the life of the author – it would also be the last of its kind – to exclusively contain a selection of his paintings. Still today, there are very few who know that Gibran in addition to being a great writer, was also an extraordinarily talented painter. He studied at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and trained with some of the major artists of the beginning of the last century, including Auguste Rodin, who it is said defined him as “the William Blake of the twentieth century.” In 1908, Gibran was even awarded the silver medal at the Salon du Printemps.

From early childhood, when he was dazzled by the intuitions of Leonardo and Michelangelo (he must have been aware of Michelangelo’s Prisoners when he painted Woman with Garment), the artist endlessly used pencil, palette and color to produce hundreds of drawings and paintings, to the extent that his last wish before dying was that someone sees to gathering and displaying all of his work so that people could admire and “perhaps even love” it. His paintings and drawings are currently exhibited in some of the most important galleries and museums the world over, that include the Metropolitan in New York, and exhibitions of his work are regularly held in America, the Middle East and Europe.

But before being an artist of the pen and of the paintbrush, Gibran was a mystic, and it is for this reason that the instruments used by the critics, whether literary or of the arts, have often proved to be inadequate in approaching his creative genius. Furthermore, scholars have only rarely been concerned with the study of his figurative production, considering it to be a subordinate or minor form of expression as compared to his poetry. And yet, his painting so deeply harmonizes with his writing that it is impossible to conceive of one without the other.

Close to Islam and to Eastern religions, Gibran grew up in a family of Maronite faith (that is, Christian with Eastern rites), but would later develop a syncretic credo that was totally personal and original, and by many defined “Gibranism.” Art and poetry for Gibran were never an intellectual exercise, rather, they were a spiritual one, a means of elevating man to a knowledge of the divine. In Gibran, artistic-poetic inspiration becomes a revelation, an epiphany of God: “Art is a step from nature towards the Infinite,” it is a bridge between matter and spirit. Pictorial art is the contemplation of human beauty, the manifestation of sensitive perfection, perceived in its nakedness – the nude being practically the only subject in Gibran’s painting – proof of the immanent reality of the Creator present in his creatures.

Beauty, as may be read in the eponymic sermon of The Prophet, must be “way and guide” in the existence of each one of us. Better still, it coincides with life itself – because “where beauty is, there are all things.” It is, thus, the arbiter and the essence of Gibran’s art, an art that becomes a mystical-aesthetic experience, a pathway to the original and absolute, ineffable and eschatological truths of man. When Gibran creates, he is inspired by a deep love for and acknowledgement of beauty, and this allows him to express his universal message to all of humanity. The translucent purity of his paintings leads towards a more sacred place, the heart itself of the human being, because “every picture is a portrait, a self-portrait.” Gibran the artist, hence, is situated at the crossroads between East and West, without necessarily belonging to either one, between symbolists and visionaries, between classicists and romantics, and it is precisely in the fusion of these opposing tendencies, in the reconciliation of opposites, that he comes to surpass schools, faiths and traditions.

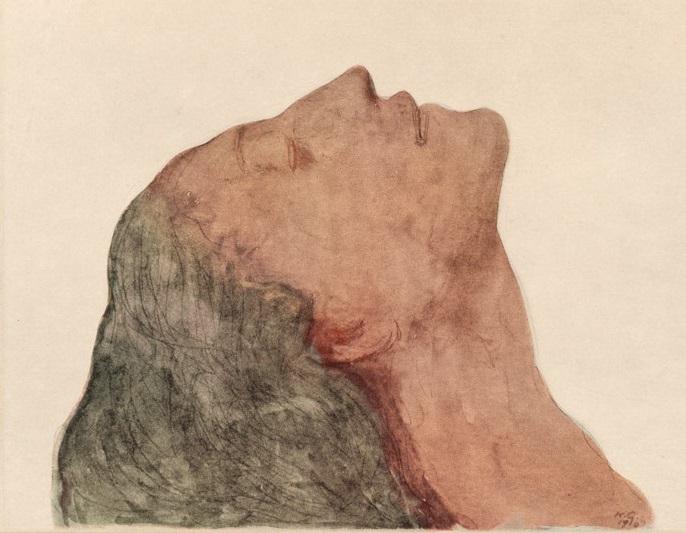

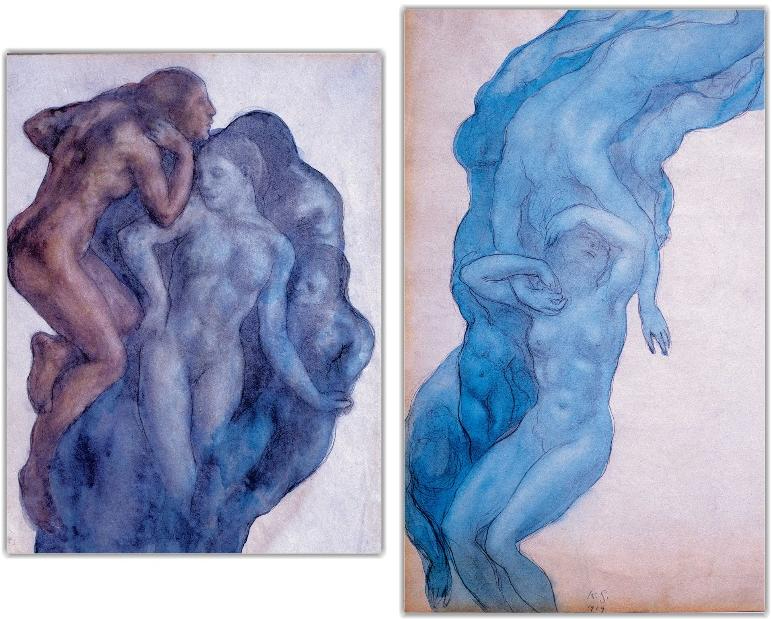

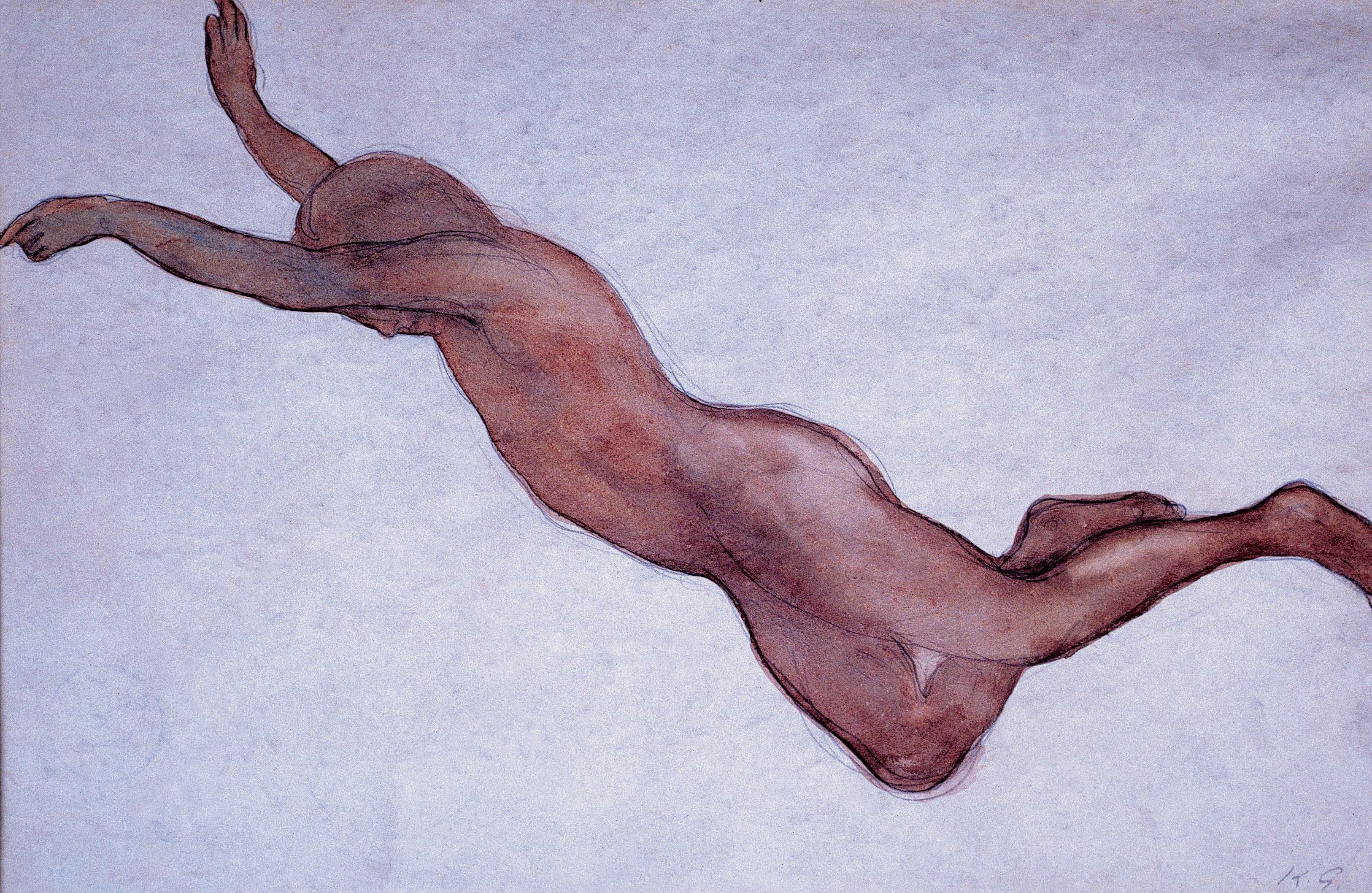

Twenty Drawings, with a prefatory essay by Alice Raphael previously published in the prestigious American journal “The Seven Arts” in 1917, is a collection of watercolors that represent the human form as an image and personification of Beauty, an icon of Life, an emanation of the Eternal. The backgrounds appear to be indistinct or populated by vague figures that are merely sketched, ectoplasmic, like the glimmer of dreams. Gibran’s creatures – even those portrayed in works that attempt to obtain a sculptural vigour – are weightless, they have no musculature, and are nearly volatile, delivered into a dimension that is atemporal, other-worldly, beyond the heavens, because they belong to the author’s unconscious.

Or, better yet, to the collective unconscious, to “our world of vision,” because “we are creatures of form and color.”The Spirit is expressed and communicated in the inner vision of human life, made of light and aesthetic contours. The pencil, at times, joins the paintbrush in order to perfect and emphasize a subject, the gradation of the color being extremely delicate (livelier red and blue hues are rarely seen); at first, it appears that only a minimal amount of color has been used, but we gradually realize that it is really all color, diffused imperceptibly, yet sufficient to provide shape to the forms.

Gibran was defined as a “visionary,” but he did not consider himself a visionary, at least, no more than anyone else: “To see the vision is but to open our eyes.” The practice of the visionary, in fact, initiates from what is real, from the known visible, in order to attain the unknown invisible. By antithesis, the theme of blindness frequently recurs in the artist’s literary and pictorial production, and it is used in an ambivalent sense. There are those who, far from the spiritual light, live unknowing of any awareness (“blind-hearted”), and those who, instead, have developed a perception of and a direct relationship with the divine and its manifestations without being distracted by maya, by the illusion of the phenomenal world.

Gibran was defined as a “visionary,” but he did not consider himself a visionary, at least, no more than anyone else: “To see the vision is but to open our eyes.” The practice of the visionary, in fact, initiates from what is real, from the known visible, in order to attain the unknown invisible. By antithesis, the theme of blindness frequently recurs in the artist’s literary and pictorial production, and it is used in an ambivalent sense. There are those who, far from the spiritual light, live unknowing of any awareness (“blind-hearted”), and those who, instead, have developed a perception of and a direct relationship with the divine and its manifestations without being distracted by maya, by the illusion of the phenomenal world.

In the Koran it is God himself, described as “light of the heavens and the earth,” who invites men to “lower their eyes” (24,30), to use their spiritual eyes to look away from habitual deception and from the falseness of things of the senses. This is the motif in the dark portrait of a man titled The Blind. Those who are able to perceive the inner sphere of their being, the “Greater Self” – that is, God in man, based on the fundamental conception of the Sufi (Islamic mystics) – are illuminated. They may then close their eyes to each and every imperfect thing in contemplation of God, who is extraneous to each and every imperfection: true beauty is “an image you see though you close your eyes.”

look away from habitual deception and from the falseness of things of the senses. This is the motif in the dark portrait of a man titled The Blind. Those who are able to perceive the inner sphere of their being, the “Greater Self” – that is, God in man, based on the fundamental conception of the Sufi (Islamic mystics) – are illuminated. They may then close their eyes to each and every imperfect thing in contemplation of God, who is extraneous to each and every imperfection: true beauty is “an image you see though you close your eyes.”

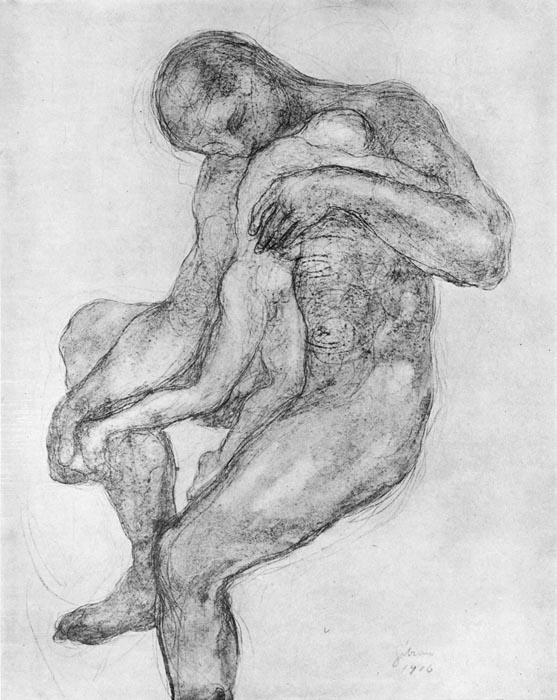

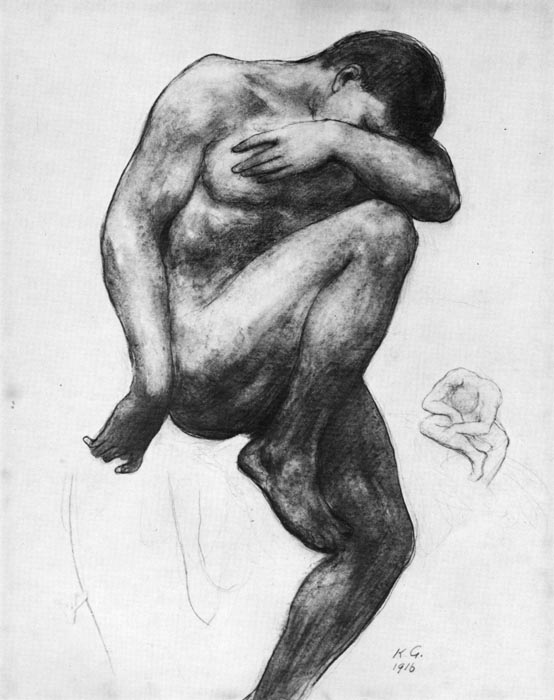

Mother and Child is also a portrayal of the Sufi principle of “Greater Self”. The smaller nature of man is upheld by the greater one (whose semblance is maternal, because Gibran sustained a feminine ideal of the divine). The “Greater Self”, God, is very close – “closer to man than the jugular vein itself” (Kor. 50,16) – but although he desires Him, he does not see Him, because the face of this divine being appears before him covered with a veil. It is again the beauty that represents absolute good, the God that is hidden in the intimacy of man, our common original reality: “beauty is life when life unveils her holy face.” The search for beauty thus means inclining to God because it represents the divine image in the world; but the ascetic tension in man is held back by that part of him that is worldly and temporal:

“There’s something big in me and I can’t get it out it’s a silent greater self, sitting and watching a smaller me do all sorts of things. All the things I do seem false to me; they are not what I want to say. I am always conscious of a birth that is to be. It’s just as if for years a child wanted to be born and couldn’t be born. You are always waiting, and you are always in birth pain. Yet there is no birth.” Beauty is the medium, “beauty is a path that leads to self self-slain”, to our deepest being. Only by filtering human existence through the icon of beauty are we able to perceive divine essence.

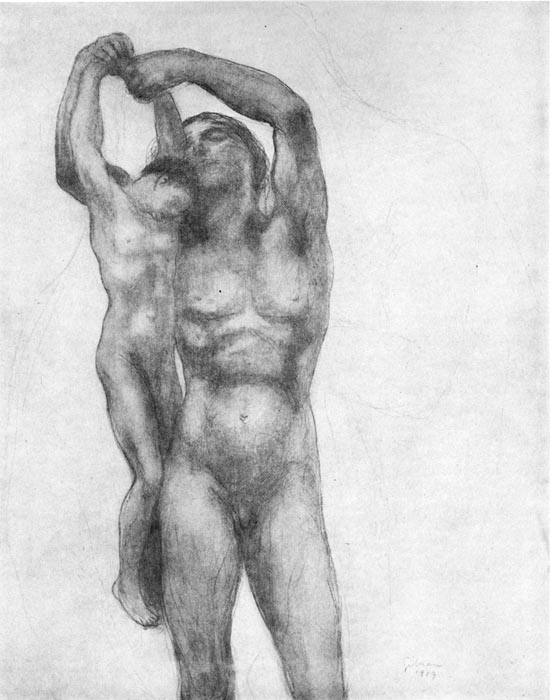

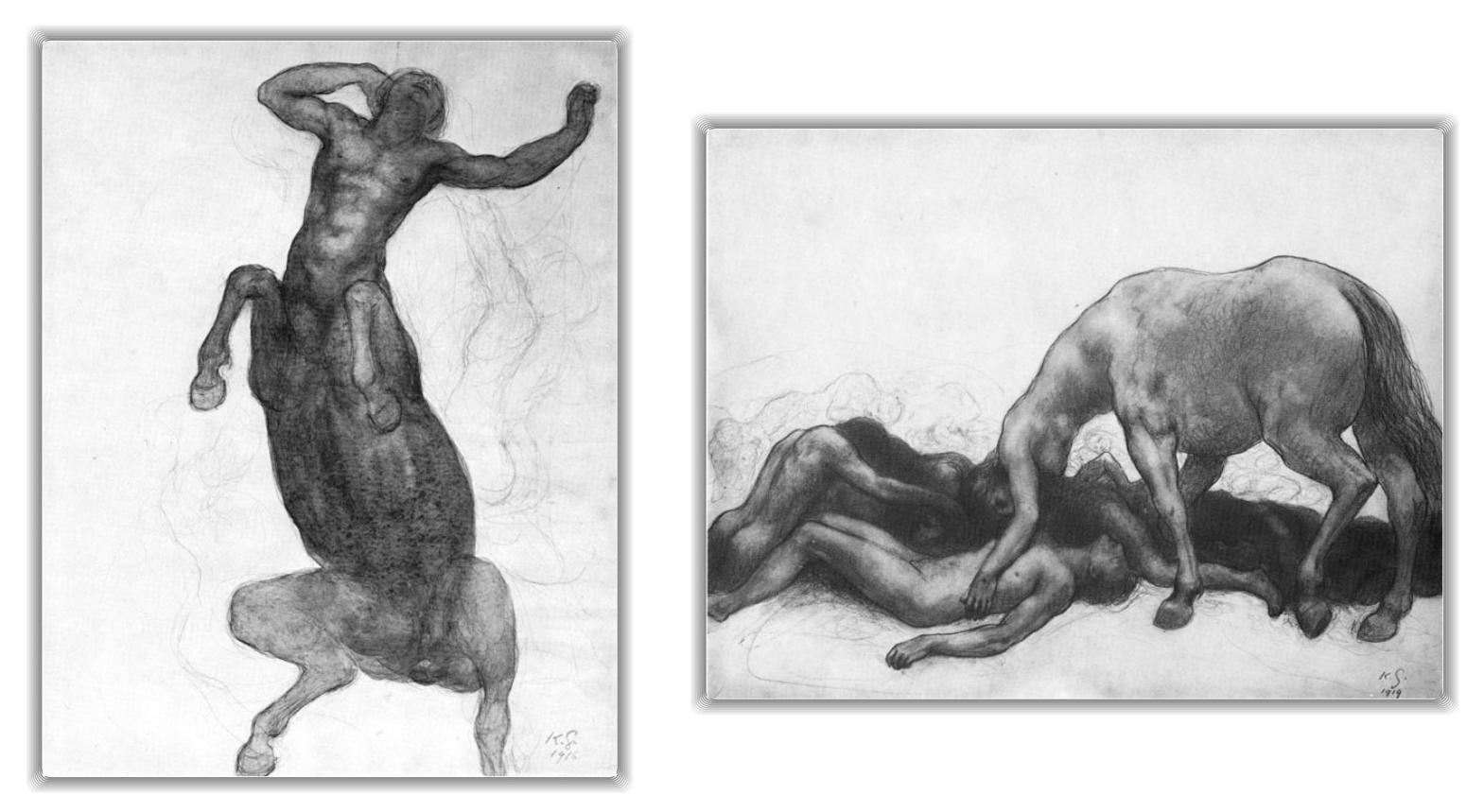

The motif of man’s struggle or his encounter with brute nature is represented by Gibran in his series of centaurs, a subject clearly derived from Michelangelo and Rodin.  The individual is portrayed in his dual nature: although indissolubly bound to worldly existence (his hooves are well-set in the ground), the human bust of the fabled creature is arched and his arms are outstretched towards the sky, as he attempts to raise himself from his beastly condition. It is the drama of the soul, whose impulses often remain miserably frustrated by corporeal nature. In Centaur and Child, it is a woman who is portrayed in her duality, in the desperate, compassionate, vain, lacerating act of keeping the innocence of the newborn child from the lowly, obscure material world (dunya), a place of affliction, where she herself is inevitably a prisoner. But through his portrayal of delicate and graceful centaurs, Gibran’s purpose is also that of examining the mysterious relationship between the microcosm of man and the macrocosm. Man, although conscious of being intimately related to the creation and to its cosmic developments, is incapable of defining his place in the universe and his belonging to God.

The individual is portrayed in his dual nature: although indissolubly bound to worldly existence (his hooves are well-set in the ground), the human bust of the fabled creature is arched and his arms are outstretched towards the sky, as he attempts to raise himself from his beastly condition. It is the drama of the soul, whose impulses often remain miserably frustrated by corporeal nature. In Centaur and Child, it is a woman who is portrayed in her duality, in the desperate, compassionate, vain, lacerating act of keeping the innocence of the newborn child from the lowly, obscure material world (dunya), a place of affliction, where she herself is inevitably a prisoner. But through his portrayal of delicate and graceful centaurs, Gibran’s purpose is also that of examining the mysterious relationship between the microcosm of man and the macrocosm. Man, although conscious of being intimately related to the creation and to its cosmic developments, is incapable of defining his place in the universe and his belonging to God.

It would be the purpose of Gibran’s art to attempt to express precisely that unity responsible for the close relationship between man and nature, regaining each fragmentary element of existence in order to lead man back to God. This is the theory developed by the Sufi of the wahdat al-wujud (the unity of Being and of Existence) based on which God is the only true being, and all else is nothing but a manifestation of the multiplicity of divine oneness. What derives from this is that the only way for man to feel accomplished, as he participates in the same existence of all things created and present in nature, is for him to be recomprehended in his Creator. For Gibran, art must not imitate nature, rather, its purpose is to unveil its mysteries: “Art is born when the artist’s secret vision coincides with the manifestation of nature in the search for new forms. ” the Waterfall, The Rock, The Mountain, hence, are works that reveal human bodies grouped together to assume the form that is suggested in the titles: “I want this exhibit to be just the human form in its relation to other forms – trees, rocks – other forms of life – that peculiar wiry something.” Moreover, for Gibran, people must necessarily once again learn “the chastity of the nude,” because the body, enclosing within itself beauty and freedom, is the truest and noblest symbol of life itself: “I always draw the bodies naked because life is naked. If I draw a mountain as a heap of human forms or paint a waterfall in the shape of tumbling human bodies, it is because I see in the mountain a heap of living things, and in the waterfall a precipitate current of life.” The stone, like man, is also a part of creation: “You and the stone are one. There is a difference only in heartbeats. Your heart beats a little faster.” In the work titled The Rock, it is a symbol of strength and solidness, bodies are grouped to delineate the contours of a closed fist, thus symbolizing the immortality of existence, its eternity.

of existence in order to lead man back to God. This is the theory developed by the Sufi of the wahdat al-wujud (the unity of Being and of Existence) based on which God is the only true being, and all else is nothing but a manifestation of the multiplicity of divine oneness. What derives from this is that the only way for man to feel accomplished, as he participates in the same existence of all things created and present in nature, is for him to be recomprehended in his Creator. For Gibran, art must not imitate nature, rather, its purpose is to unveil its mysteries: “Art is born when the artist’s secret vision coincides with the manifestation of nature in the search for new forms. ” the Waterfall, The Rock, The Mountain, hence, are works that reveal human bodies grouped together to assume the form that is suggested in the titles: “I want this exhibit to be just the human form in its relation to other forms – trees, rocks – other forms of life – that peculiar wiry something.” Moreover, for Gibran, people must necessarily once again learn “the chastity of the nude,” because the body, enclosing within itself beauty and freedom, is the truest and noblest symbol of life itself: “I always draw the bodies naked because life is naked. If I draw a mountain as a heap of human forms or paint a waterfall in the shape of tumbling human bodies, it is because I see in the mountain a heap of living things, and in the waterfall a precipitate current of life.” The stone, like man, is also a part of creation: “You and the stone are one. There is a difference only in heartbeats. Your heart beats a little faster.” In the work titled The Rock, it is a symbol of strength and solidness, bodies are grouped to delineate the contours of a closed fist, thus symbolizing the immortality of existence, its eternity.

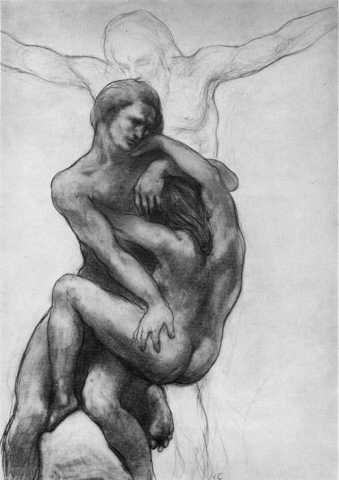

“Beauty is eternity gazing at itself in the mirror. But you are eternity and you are the mirror.” It is the divine Spirit that asks man to live according to beauty, the uniting principle of being. Existence, permeated by joy and pain, by matter and spirit, may contemplate the face of eternity by looking at its own reflection in the mirror of beauty. To the common man who confuses beauty with his unrequited desires, Gibran says that “beauty is not a need but an ecstasy.” Only he who, like Buddha, transcends every desire, observing through the eyes of the spirit from the highest peaks of awareness, is capable of understanding the meaning of beauty that cannot be reduced to a corporeal sensation, and that disconcerts the mind. Beauty lies, precisely, in ecstasy, in the mind’s emerging from itself, and that in so doing abandons each and every sensitive and intellectual experience in the achievement of a state of communion and identification with the divine.  Flight, which seems to refer to the myth of Icarus, perhaps alludes to the failure of he who is convinced that God may be understood through intellect alone. Or perhaps it is simply the portrayal of the joyous and innate tension in each individual that accompanies a return to God, rather, a becoming God. For the Christian Gibran, the incarnation of the Sufi ideal of the “Perfect Man” (al-Insan al-Kamil), that is, he who has obtained the highest level of proximity to God, is Jesus, the beloved “Master of Light”, the unequalled myth of aesthetic and spiritual beauty, unwavering proof of the absolute presence of God before man. In the artist’s opinion, the crucifixion is the highest expression of the greatness of Christ, an event that signifies freedom from matter, the sole cause of suffering man’s longing for the infinite. Crucified portrays two human figures that hold on to a third figure, and proves in exemplary fashion how the traditional image of Christ between the two thieves may also be used in a symbolic sense – there are no explicit religious elements such as the cross, blood or nails to be seen here (The Triangle is equally allusive, as it seems to represent a sacred deposition).

Flight, which seems to refer to the myth of Icarus, perhaps alludes to the failure of he who is convinced that God may be understood through intellect alone. Or perhaps it is simply the portrayal of the joyous and innate tension in each individual that accompanies a return to God, rather, a becoming God. For the Christian Gibran, the incarnation of the Sufi ideal of the “Perfect Man” (al-Insan al-Kamil), that is, he who has obtained the highest level of proximity to God, is Jesus, the beloved “Master of Light”, the unequalled myth of aesthetic and spiritual beauty, unwavering proof of the absolute presence of God before man. In the artist’s opinion, the crucifixion is the highest expression of the greatness of Christ, an event that signifies freedom from matter, the sole cause of suffering man’s longing for the infinite. Crucified portrays two human figures that hold on to a third figure, and proves in exemplary fashion how the traditional image of Christ between the two thieves may also be used in a symbolic sense – there are no explicit religious elements such as the cross, blood or nails to be seen here (The Triangle is equally allusive, as it seems to represent a sacred deposition).

That which the artist means to express is again the inner strife of every human being – two loves that are distinct but of equal intensity, two contrasting natures, thus representing extreme suffering, agony. In the words of Gibran’s friend and biographer Mikhail Naimy: “What greater pain can there be than the pain of love becoming a cross to the lover? On the other hand, what joy can be greater than the joy of Love leading to the cross, and from the pains of the cross to the bliss and emancipation of Love triumphant?”. In short, beauty for Gibran is “a heart inflamed and a soul enchanted,” the sole path that leads to truth. But the path and the destination do not diverge; in the end, the path itself becomes a destination. The first step taken is also the last.

Bibliography

Kahlil Gibran, Twenty Drawings, New York: Knopf, 1919:

Alice Raphael, The Art of Kahlil Gibran, The Seven Arts, March, 1917, pp. 531-534: