-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

By Francesco Medici

all rights reserved copyright © 2023

In the month of May 1903, Ameen Goryeb (Amīn al-Ġurayyib, 1880-1971), editor and owner of «al-Mohajer» (‘The Emigrant’), a daily Arabic newspaper published in New York, visited the city of Boston. Among the people who received him was the young Kahlil Gibran (Ǧubrān Ḫalīl Ǧubrān, 1883-1931), who captured the journalist’s regard with his kind manner and intelligence. The following day, Gibran invited Ameen to his home. He showed him his paintings and presented him with an old notebook in which he had set down his thoughts and meditations. When Ameen saw the paintings and read the poems in the notebook, he realized he had discovered a genius artist, poet, and philosopher.

Thrilled by his discovery, the journalist offered Gibran a position as a columnist on «al-Mohajer». Thus, Ameen Goryeb extracted Gibran from his retreat in Boston and introduced him to his Arabic readers. «This newspaper is very fortunate» wrote Goryeb in one of his editorials, «to be able to present to the Arabic-speaking world the first literary fruit of a young artist whose drawings are admired by the American public. This young man is Ǧubrān Ḫalīl Ǧubrān of Bišarrī [Bcharré], the famous city of the braves. We publish this essay without comments under the caption of Dam‘ah wa Ibtisāmah [A Tear and a Smile], leaving it up to the readers to judge it according to their tastes.»[1] This was the first time that Gibran saw his name in print.

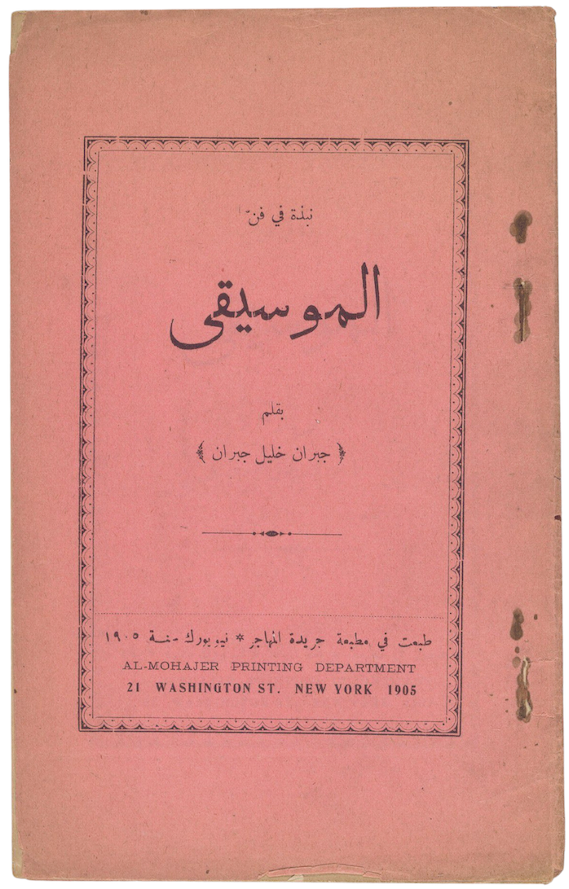

It was Ameen Goryeb himself, through «al-Mohajer» printing department, who published Gibran’s first book, Nubḏah fī Fann al-Mūsīqá (A Short Treatise on the Art of Music), also known simply as al-Mūsīqá (The Music).[2] Published in 1905 in New York, this essay of about 20 pages marks the author’s debut into the world of letters. Despite its title, the treatise is more a prosaic ode to music than an objective dissertation on it. As such, it tells us more about Gibran, the emotional, than its subject. The Gibran it reveals is a flowery sentimentalist who, saturated with a vague nostalgic sadness, sees in music a floating sister spirit, an ethereal embodiment of all that a nostalgic heart is not and yet yearns to be.

In truth, the opinions of critics and scholars were and are not very gratifying with the book. For example, Suheil B. Bushrui (Suhayl Badī‘ Bušrū’ī, 1929-2015) wrote that «al-Mūsīqá, as a work of art, betrayed all the characteristics of neophyte apprenticeship. There was no lack of passion, but the fire of his imagination was dampened by an ornate style, a languid tone, and uncertain rhythm.»[3] According to the famous Lebanese poet Khalil S. Hawi (Ḫalīl Salīm Ḥāwī, 1919-1982), Gibran’s «descriptions of music are so vague that we could as well apply them to poetry, love or any other subject which can excite emotion in the heart.»[4]

In his book, Gibran begins by likening music to the sound of the voice and speech of his beloved woman (probably, the American poet and dramatist Josephine Preston Peabody [1874-1922]). Then, the poetic essay focuses on the divine sources of music, its history and its role in the civilizations of the past – ancient Chaldean, Egyptian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Hebrew, Assyrian, and Indian cultures. It continues describing and paying special homage to four maqāmāt (maqām is the system of melodic modes used in traditional Persian, Arabic, Turkish and Andalusian music). Ultimately, the author calls upon listeners to glorify Orpheus, David, Beethoven, Wagner, and Mozart, and especially urges his fellow Syrians to remember the great musical traditions embodied in the Arab composers (Ibrāhīm al-Mawṣilī [742-804], Isḥāq al-Mawṣilī [767-850], Šākir al-Ḥalabī and ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī [1841-1901]).

Among Gibran’s books, al-Mūsīqá is undoubtedly the least known, the least studied, and also the least translated. For my part, I had always wanted to have a complete Italian translation of it because al-Mūsīqá – for its sublime poetic style and evocative power – can be considered, in a certain sense, as a prelude to Gibran’s masterpiece, The Prophet. Unfortunately, I could not translate it by myself for two main reasons: my inadequate knowledge of Arabic and my total ignorance of technical aspects of both Western and Eastern classical music.

On a spring day in 2020, during the lockdown, in Italy as in Lebanon, I got a digital copy of the first original edition of the book, and precisely the copy that the author gave and dedicated to his American patroness Mary Haskell. It was then that I made a great discovery: on the frontispiece, I noticed the word ‘Musica’, handwritten by Gibran himself in Italian! It is not surprising that Gibran knew that Italian word. At that time, in New York, Little Syria and Little Italy had close relationships. In addition, Italian music, in general, and Neapolitan music, in particular, were very popular, also among Arab Americans.

I took that word – ‘Musica’ – as a sign of destiny. So, I had the idea to contact two dear Lebanese friends of mine to help me with my translation project: Dr. Maya El Hajj (Notre Dame University-Louaize, Lebanon), as an expert in translation and Arab American literature, and Mrs. Nadine Najem, as a poet, translator, musician and musicologist – both of them perfectly fluent in the Italian language. When they were translating the text, I was working on an introductory essay (as a Gibran scholar, I had a fairly accurate knowledge of both the contents of the book – also thanks to some translations, complete, or only partial, in English and French –, and of the precise circumstances under which it was composed). Then, I revised Dr. El Hajj and Mrs. Najem’s fine Italian version of the text while they were committed to translating or, better, to rewriting my introduction into Arabic – our shared intention was to have a bilingual critical book.

La musica[5] is not only the first Italian translation of Nubḏah fī Fann al-Mūsīqá but also a philological way to return to Arabic-speaking readers the work as well as Gibran conceived and composed it. All this took a lot of hard work, but today we can see and share with you the precious fruits of our collaboration, of this our profitable experience. Finally, our book, released by the Sicilian publishing house Mesogea, in collaboration with EduLibano and EduBeyond, and under the high patronage of the Embassy of Lebanon in Rome, the International Centre for Human Sciences-UNESCO Byblos, the Notre Dame University-Louaize, the Italian Cultural Institute, the Gibran National Committee, and the Gibran Museum, is really a bridge, or, to quote Gibran’s The Prophet, an example of “love made visible”, between Italy and Lebanon.

*This article is based on a discourse delivered by Francesco Medici at the International Conference "Language and Translation: Cross-Cultural Contexts," held at Notre Dame University-Louaize in Zouk Mosbeh, Lebanon, on March 22, 2023.

[1] Kahlil Gibran: A Self-Portrait, translated from the Arabic and edited by Anthony R. Ferris, New York: The Citadel Press, 1959, p. 21 (cf. Amīn al-Ġurayyib, Ǧubrān Ḫalīl Ǧubrān, «al-Ḥāris», 8, 1931, pp. 689-704).

[2] Ǧubrān Ḫalīl Ǧubrān, Nubḏah fī Fann al-Mūsīqá, New York: Maṭbaʻat Ǧarīdat al-Muhāǧir, 1905. (https://www.kahlilgibran.com/archives/written-works/115-nubdhah-fi-fann-al-musiqa-the-music-new-york-ma-ba-at-jaridat-al-muhajir-1905-pocket-edition/file.html)

[3] Suheil Bushrui & Joe Jenkins, Kahlil Gibran: Man and Poet. A New Biography, Oxford-Boston: Oneworld, 1998, p. 72.

[4] Khalil S. Hawi, Kahlil Gibran: His Background, Character and Works, Beirut: American University of Beirut, 1963, p. 245.

[5] Kahlil Gibran, La musica / Nubḏah fī Fann al-Mūsīqá, edited and translated by Francesco Medici, Dr. Maya El Hajj, Nadine Najem, foreword by Dr. Paolo Branca, Messina (Italy): Mesogea, 2023.