-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

by Francesco Medici

all rights reserved Francesco Medici Copyright 2024 ©

The Ottoman Empire entered World War I as one of the Central Powers (together with the German and the Austro-Hungarian Empires) with a surprise attack on Russia’s Black Sea coast on October 29, 1914, which prompted Tsar Nicholas II (1868-1918) and his allies of the Entente – Great Britain and France – to declare war on the Sublime Porte in November. Allied forces blockaded the Eastern Mediterranean coastal ports in order to strangle the economy and weaken the Ottoman war effort. In response to that, Djemal Pasha (Ahmet Cemâl Paşa, 1872-1922), commander of the Turkish Fourth Army and Governor of Syria, convinced that an uprising among local Arabs – of Christian faith, in particular – was imminent, deliberately barred crops from entering from the neighboring Syrian hinterland to Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, a semi-autonomous subdivision of the Ottoman Empire which had been created after 1861 as a homeland for the Maronite Christians under European diplomatic pressure.

In September 1915, Ali Munif Bey (Ali Münif Yeğenağa, 1874-1950), one of the senior officials of the Ottoman Ministry of Interior, was appointed as administrator of Mount Lebanon. He devoted his works to the abolition of the Mount Lebanon regime and its privileges so, during his administration (1915-1917), many leading Arabs were tortured and executed, and notable families were deported. In addition, since March of 1915, a natural disaster befell Mount Lebanon: dense locust swarms stripped areas of the Levant of almost all vegetation, and this infestation seriously compromised the already-depleted food supply of the region. Djemal’s policies did nothing to alleviate the suffering of the defenseless people. Among the consequences of such a convergence of political and environmental factors there was the so-called Great Famine of Mount Lebanon, which, between 1915 and 1918, would lead to the deaths of nearly half of its inhabitants from hunger and disease.[1]

By the summer of 1915 the Lebanese community in America started receiving the first confused and fragmentary grave news about what was happening to their families and friends in their cities and villages overseas:

“An army of beggars appeared in Beirut, and the sight of emaciated men, women, and children ransacking garbage cans or eating the dead carcasses of animals became commonplace. Others too weak to continue the struggle died in the streets. Meanwhile, the entire land became plagued by disease. House flies spread typhoid, body-lice typhus, rats bubonic plague, mosquitoes malaria, and swarms of locusts veiled the sun. During this terrible period, some 100,000 people […] died.”[2]

In those agonizing days, Kahlil Gibran (Ǧubrān Ḫalīl Ǧubrān, 1883-1931) was on vacation with her sister Marianna (Maryānā Ḫalīl Ǧubrān, 1855-1972) and some visiting relatives. They had found a small cottage in Jerusalem Road, Cohasset, a seaside village twenty-five miles south of Boston. On September 10, 1915, he wrote a letter to his friend and patroness, Mary Elizabeth Haskell (1873-1964) to decline a dinner invitation from her by providing the following reasons:

“I am leaving this place in an hour or so for New York. Last night I received a telegram and this morning a letter, both urging me to go and attend to a Syrian affair in which I promised to take part […]. The poor people of Syria are suffering very much and we are trying here to help as much as we could. It is so hard for me to say ‘no’ to a thing of this sort.”[3]

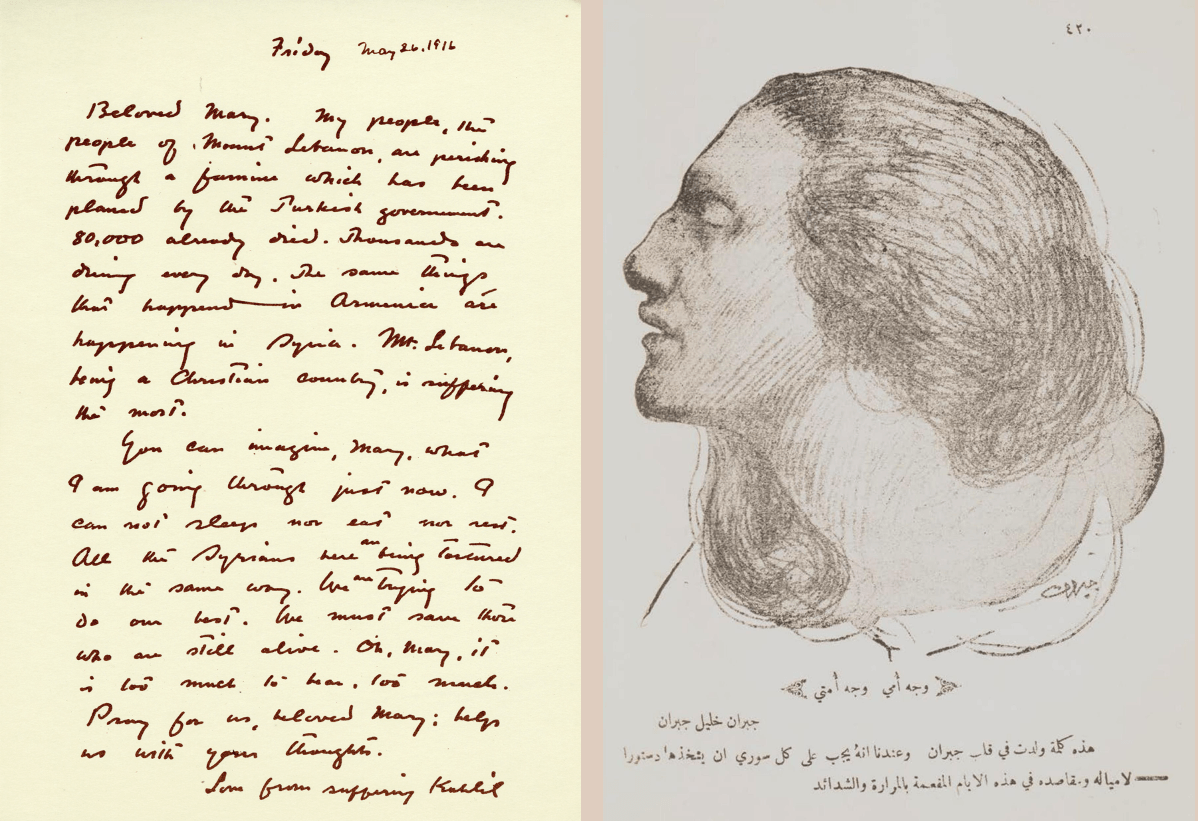

In the following months, the number of victims of the famine that was sweeping his homeland was continuously increasing, and also communications between Mount Lebanon and the rest of the world had become cut off. Gibran began sending small sums of money to Syria and promised to contribute the royalties from his latest book, Dam‘ah wa Ibtisāmah (A Tear and a Smile),[4] to the effort. In the spring of 1916, he found himself being drawn into soliciting funds for his beleaguered country. By now, he was conscious that such a disaster had been planned by the Ottoman government and that the same atrocities that had befallen the Christian population in Armenia – when over a million people had been massacred by Turkish troops – were now occurring in the predominantly Christian area of Mount Lebanon. On May 26, 1916, he wrote to Mary Haskell:

“My people, the people of Mount Lebanon, are perishing through a famine which has been planned by the Turkish government. 80,000 already died. Thousands are dying every day. The same things that happened in Armenia are happening in Syria. Mt. Lebanon, being a Christian country, is suffering the most. You can imagine, Mary, what I am going through just now. I cannot sleep nor eat or rest. All the Syrians here are being tortured in the same way. We are trying to do our best. We must save those who are still alive. Oh, Mary, it is too much to bear, too much. Pray for us, beloved Mary; help us with your thoughts.”[5]

On reading of the genocide in Mount Lebanon, Mary sent him a generous check for four hundred dollars. Kahlil, thinking the amount of the donation too extravagant from an American citizen, on May 29 wrote her back:

“I want the Syrians here to feel that they must unite and help themselves before others can help them. Of course, the Syrians alone cannot save Mt. Lebanon, but they must organize, and then this country [USA], this kind and mighty country, will save Mt. Lebanon as she has saved other countries.”[6]

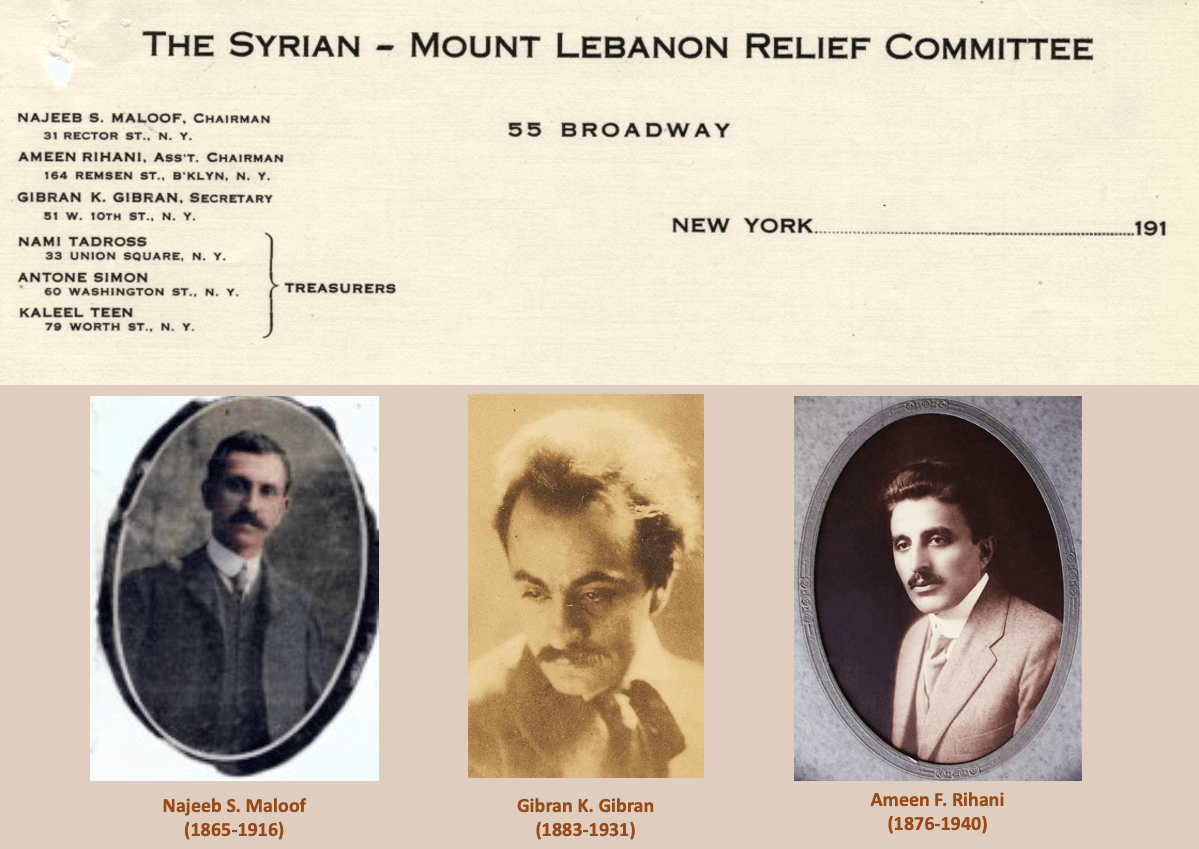

The Syrian-Mount Lebanon Relief Committee was formed in early June 1916 in Brooklyn, New York, under the chairmanship of Najeeb Shaheen Maloof (Naǧīb Šāhīn Ma‘lūf, 1865-1916), a lace importer, and the assistant chairmanship of the famous writer and poet Ameen Rihani (Amīn Fāris al-Rīḥānī, 1876-1940), for the purpose of raising funds in the USA to combat the famine in the region. The treasurers were Nami T. Tadross (Ni‘mah Tādrus), Antone Simon (Anṭūn Sam‘ān) and Kaleel Teen (Ḫalīl al-Tīn). Appointed as its secretary, Gibran was now an official spokesperson. On June 11, he communicated to Mary that piece of news:

“We have organized, and a relief committee has been formed, and we shall all do our best. And they elected me secretary of the committee: that means that I shall have no personal life, no work of my own and no rest during this summer. I know, Mary, that it is a great responsibility, both physical and mental, but I must shoulder it to the very end, no matter how great it is. Great tragedies enlarge the heart and create the desire to serve and to be selfless. I have never been given the chance to serve my people in a work of this sort. I am glad I can serve a little and I feel that God will help me. And I do not know what is going to happen to me tomorrow or the day after. I shall simply trust myself to life. It is more than probable that I shall have to travel through the country [USA] and talk to the Syrians. We must get the machine going first in New York and then in other places. […] Now, Mary, I am going to Brooklyn to work with two young men whom I have taken as secretaries. I shall have to find a third soon.”[7]

On June 14, to Mary who was asking him how and if she could be of any help to his work, although she was «an American who does not know Arabic», he replied:

“Thank you, beloved Mary, thank you. I am thanking you now on behalf of all my people. But there is nothing for you to do, Mary. The work of the committee is going well now – and we have a large number of men and women doing all sorts of things. And you have already done more than enough. The hardest work before us now is to get all the Syrians to cooperate with the people of Mount Lebanon – and then to have the Turkish government permit foodstuff to get into the country. We can manage that through the American government.”[8]

The committee soon agreed with Gibran that the Sublime Porte had deliberately provoked that human tragedy because many Syrian leaders were supporting the Allies in the war. They believed that «the only real hope […] lay in the American government using its good offices to alleviate the famine which was beginning to take on biblical proportions». On June 29, Gibran told Mary he had contacted the State Department in Washington. «However, in his heart he held out little hope, knowing that the Americans, in the dark year of 1916, had little time for his homeland».[9]

“Beloved Mary. Things are going on very well and money is coming in all the time. Of course, it will take some time and a good deal of patience to make all the Syrians of North America work together with united efforts for one thing – and only one thing. But the most difficult thing before us is getting foodstuffs into Mount Lebanon. We are quite certain now that the Turkish government wishes to starve our people because some of our leaders there are with the Allies in thought and spirit. The American government is the only power in the world that could help us. I wrote to the State Department in Washington and received an answer which assured me that this government is really using its good offices to alleviate the conditions in Syria. But you know how things are in Washington just now. Too many world problems and too many difficulties are being solved. I have given, in your name, $150 to the Relief Committee. It is the largest contribution from an American so far. The Arabian revolt is indeed a wonderful thing. No one outside of Arabia knows how successful it is and how far it will go. But the fact that there is a movement is a great and mighty thing, a thing which I have dreamt of and worked for during the past ten years. If the Arabs received help from the Allies, they would not only create a kingdom, but they would give something to the world. I know, Mary, the reality that lies in the Arabic soul. The Arabs cannot organize without the help of Europe, but the Arabs have a vision of Life which no other race possesses.”[10]

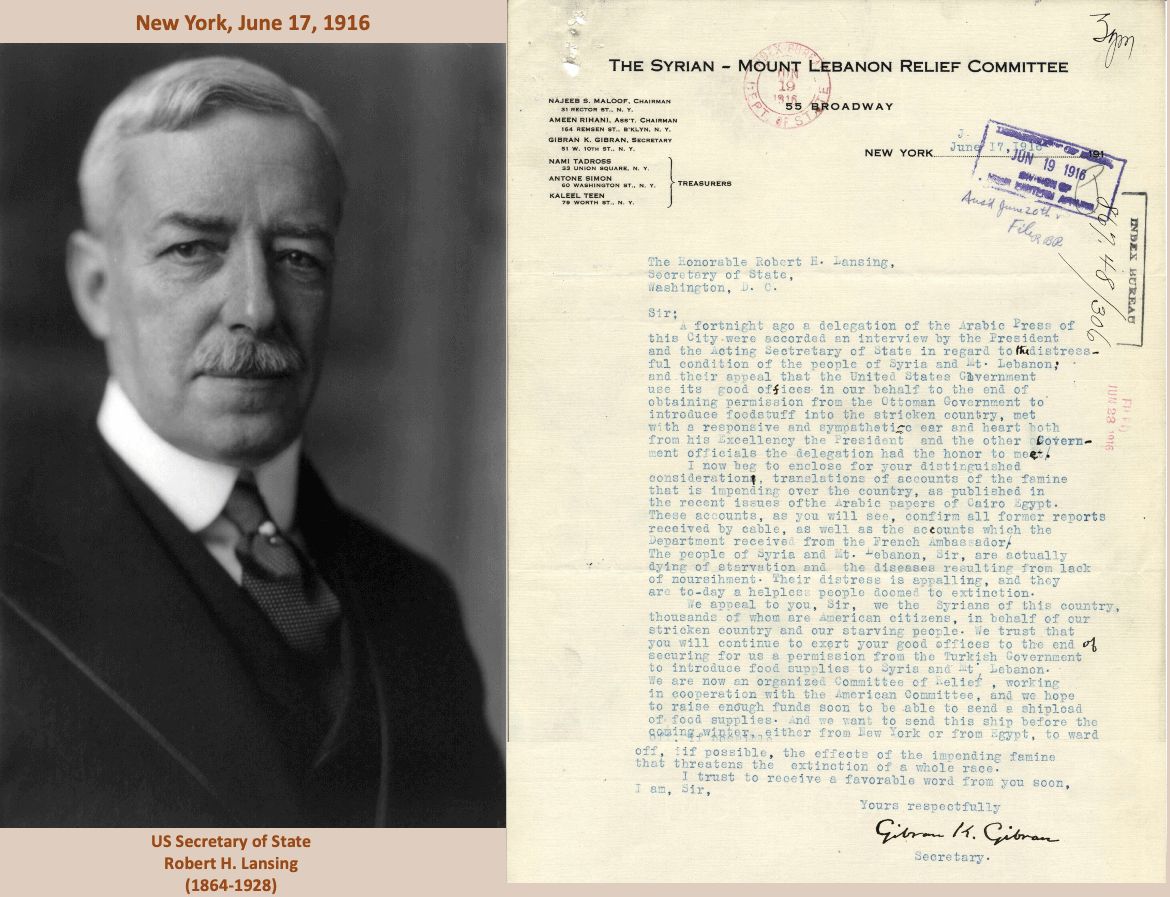

Gibran was referencing the following hitherto unpublished appeal he had written on June 17 to the appointed US Secretary of State Robert H. Lansing (1864-1928):

***

The Syrian-Mount Lebanon Relief Committee

55 Broadway

Najeeb S. Maloof, Chairman

31 Rector St., N.Y.

Ameen Rihani, Ass’t. Chairman

164 Remsen St., B’klyn, N.Y.

Gibran K. Gibran, Secretary

51 W. 10th St., N.Y.

Treasures:

Nami Tadross

33 Union Square, N.Y.

Antone Simon

60 Washington St., N.Y.

Kaleel Teen

79 Worth St., N.Y.

New York, June 17, 1916

The Honorable Robert H. Lansing,

Secretary of State,

Washington, D.C.

Sir;

A fortnight ago a delegation of the Arabic Press of this City were accorded an interview by the President and the Acting Secretary of State in regard to the distressful condition of the people of Syria and Mt. Lebanon, and their appeal that the United States Government use its good offices in our behalf to the end of obtaining permission from the Ottoman Government to introduce foodstuff into the stricken country, met with a responsive and sympathetic ear and heart both from his Excellency the President and the other Government officials the delegation had the honor to meet.

I now beg to enclose for your distinguished consideration, translations of accounts of the famine that is impending over the country, as published in the recent issues of the Arabic papers of Cairo, Egypt. These accounts, as you will see, confirm all former reports received by cable, as well as the accounts which the Department received from the French Ambassador.

The people of Syria and Mt. Lebanon, Sir, are actually dying of starvation and the diseases resulting from lack of nourishment. Their distress is appalling, and they are to-day a helpless people doomed to extinction.

We appeal to you, Sir, we the Syrians of this country, thousands of whom are American citizens, in behalf of our stricken country and our starving people. We trust that you will continue to exert your good offices to the end of securing for us a permission from the Turkish Government to introduce food supplies to Syria and Mt. Lebanon.

We are now an organized Committee of Relief, working in cooperation with the American Committee, and we hope to raise enough funds soon to be able to send a shipload of food supplies. And we want to send this ship before the coming winter, either from New York or from Egypt, to ward off, if possible, the effects of the impending famine that threatens the extinction of a whole race.

I trust to receive a favorable word from you soon, I am, Sir,

Yours respectfully

Gibran K. Gibran

Secretary.

***

With «the American Committee», Gibran meant the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief, which also adopted the cause of the starving in Mount Lebanon in addition to its increasing concern for the condition of Armenians in Ottoman Anatolia. Founded the year before at the behest of US ambassador to the Ottoman Empire Henry Morgenthau (1856-1946) and with the help of then-President Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) with the purpose of soliciting donations from the American public, the organization included in its leadership and board members eminent religious and educational figures, such as: Harvard University’s president Charles W. Elliot (1834-1926); Protestant missionary James L. Barton (1855-1936); Samuel Train Dutton (1849-1919), professor at Teachers College, Columbia University, and also a trustee of the American College for Girls at Constantinople; businessman, investor, and philanthropist Cleveland H. Dodge (1860-1926), whose son, Bayard, a scholar of Islam, would become the president of the American University of Beirut (AUB), then known as the Syrian Protestant College.

Gibran’s letter to Lansing was accompanied by translations of three anonymous first-hand accounts of the effects of the famine:

***

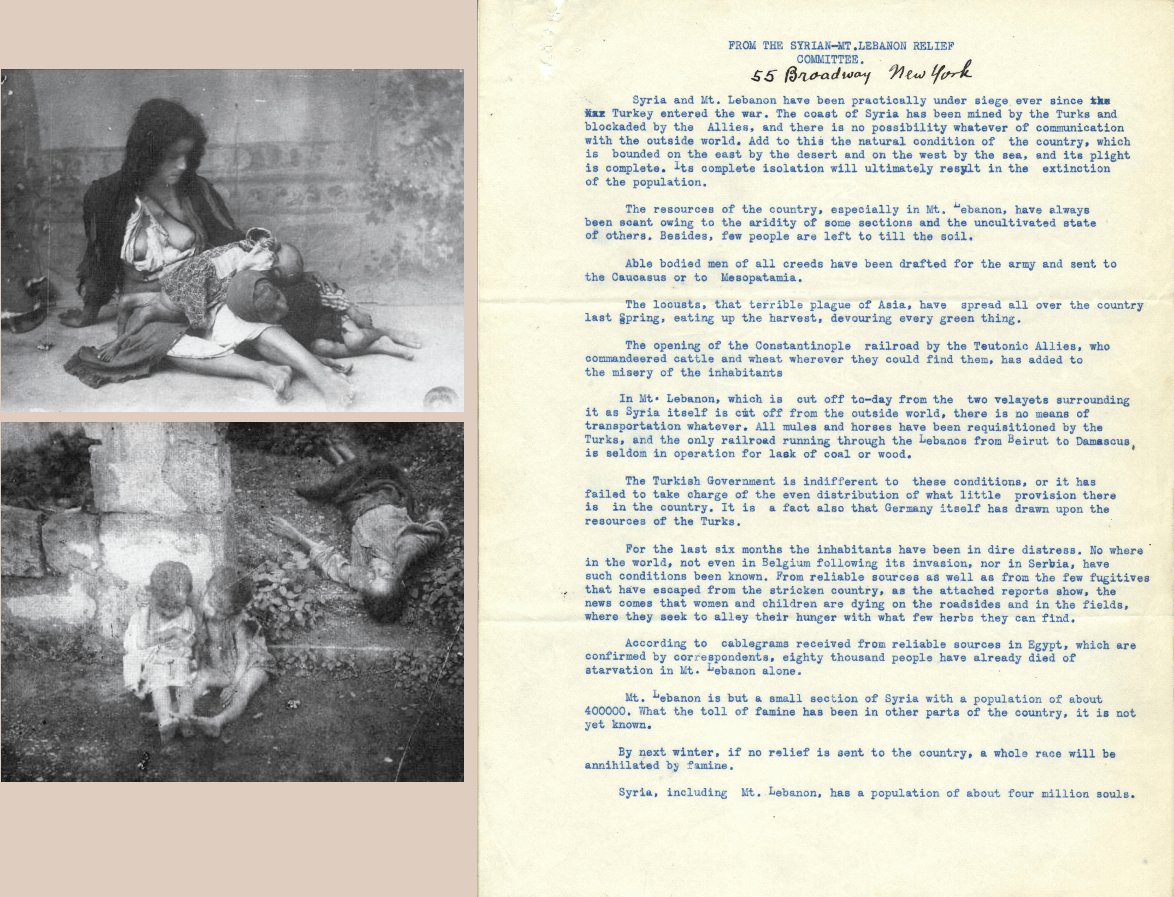

FROM THE SYRIAN-MT. LEBANON RELIEF COMMITTEE.

55 Broadway, New York

Syria and Mt. Lebanon have been practically under siege ever since Turkey entered the war. The coast of Syria has been mined by the Turks and blockaded by the Allies, and there is no possibility whatever of communication with the outside world. Add to this the natural condition of the country, which is bounded on the east by the desert and on the west by the sea, and its plight is complete. Its complete isolation will ultimately result in the extinction of the population.

The resources of the country, especially in Mt. Lebanon, have always been scant owing to the aridity of some sections and the uncultivated state of others. Besides, few people are left to till the soil.

Able bodied men of all creeds have been drafted for the army and sent to the Caucasus or to Mesopotamia.

The locusts, that terrible plague of Asia, have spread all over the country last Spring, eating up the harvest, devouring every green thing.

The opening of the Constantinople railroad by the Teutonic Allies, who commandeered cattle and wheat wherever they could find them, has added to the misery of the inhabitants.

In Mt. Lebanon, which is cut off to-day from the two vilayets[11] surrounding it as Syria itself is cut off from the outside world, there is no means of transportation whatever. All mules and horses have been requisitioned by the Turks, and the only railroad running through the Lebanons[12] from Beirut to Damascus, is seldom in operation for lack of coal or wood.

The Turkish Government is indifferent to these conditions, or it has failed to take charge of the even distribution of what little provision there is in the country. It is a fact also that Germany itself has drawn upon the resources of the Turks.

For the last six months the inhabitants have been in dire distress. Nowhere in the world, not even in Belgium following its invasion, nor in Serbia, have such conditions been known. From reliable sources as well as from the few fugitives that have escaped from the stricken country, as the attached reports show, the news comes that women and children are dying on the roadsides and in the fields, where they seek to alley their hunger with what few herbs they can find.

According to cablegrams received from reliable sources in Egypt, which are confirmed by correspondents, eighty thousand people have already died of starvation in Mt. Lebanon alone.

Mt. Lebanon is but a small section of Syria with a population of about 400000. What the toll of famine has been in other parts of the country, it is not yet known.

By next winter, if no relief is sent to the country, a whole race will be annihilated by famine.

Syria, including Mt. Lebanon, has a population of about four million souls.

***

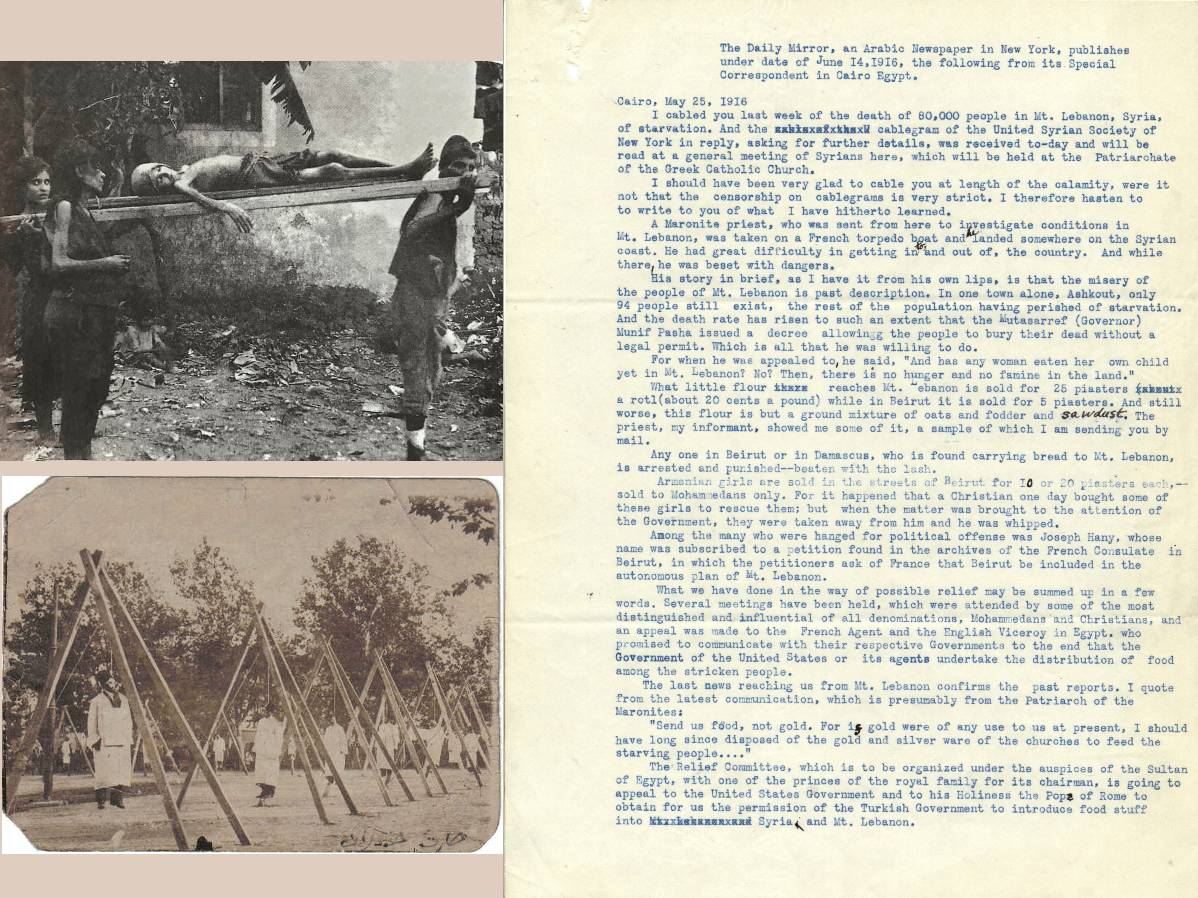

«The Daily Mirror», an Arabic Newspaper in New York,[13] publishes under date of June 14, 1916, the following from its Special Correspondent in Cairo, Egypt.

Cairo, May 25, 1916

I cabled you last week of the death of 80,000 people in Mt. Lebanon, Syria, of starvation. And the cablegram of the United Syrian Society of New York in reply, asking for further details, was received to-day and will be read at a general meeting of Syrians here, which will be held at the Patriarchate of the Greek Catholic Church.

I should have been very glad to cable you at length of the calamity, were it not that the censorship on cablegrams is very strict. I therefore hasten to write to you of what I have hitherto learned.

A Maronite priest, who was sent from here to investigate conditions in Mt. Lebanon, was taken on a French torpedo boat and he landed somewhere on the Syrian coast. He had great difficulty in getting into, and out of, the country. And while there, he was beset with dangers.

His story in brief, as I have it from his own lips, is that the misery of the people of Mt. Lebanon is past description. In one town alone, Ashkout,[14] only 94 people still exist, the rest of the population having perished of starvation. And the death rate has risen to such an extent that the Mutasarrif (Governor) Munif Pasha issued a decree allowing the people to bury their dead without a legal permit. Which is all that he was willing to do.

For when he was appealed to, he said, «And has any woman eaten her own child yet in Mt. Lebanon? No? Then, there is no hunger and no famine in the land».

What little flour reaches Mt. Lebanon is sold for 25 piasters a rotl (about 20 cents a pound) while in Beirut it is sold for 5 piasters. And still worse, this flour is but a ground mixture of oats and fodder and sawdust. The priest, my informant, showed me some of it, a sample of which I am sending you by mail.

Any one in Beirut or in Damascus, who is found carrying bread to Mt. Lebanon, is arrested and punished – beaten with the lash.

Armenian girls are sold in the streets of Beirut for 10 or 20 piasters each, – sold to Mohammedans only. For it happened that a Christian one day bought some of these girls to rescue them; but when the matter was brought to the attention of the Government, they were taken away from him and he was whipped.

Among the many who were hanged for political offense was Joseph Hany, whose name was subscribed to a petition found in the archives of the French Consulate in Beirut, in which the petitioners ask of France that Beirut be included in the autonomous plan of Mt. Lebanon.[15]

What we have done in the way of possible relief may be summed up in a few words. Several meetings have been held, which were attended by some of the most distinguished and influential of all denominations, Mohammedans and Christians, and an appeal was made to the French Agent and the English Viceroy in Egypt, who promised to communicate with their respective Governments to the end that the Government of the United States or its agents undertake the distribution of food among the stricken people.

The last news reaching us from Mt. Lebanon confirms the past reports. I quote from the latest communication, which is presumably from the Patriarch of the Maronites:[16]

«Send us food, not gold. For if gold were of any use to us at present, I should have long since disposed of the gold and silver ware of the churches to feed the starving people…».

The Relief Committee, which is to be organized under the auspices of the Sultan of Egypt,[17] with one of the princes of the royal family for its chairman, is going to appeal to the United States Government and to his Holiness the Pope of Rome[18] to obtain for us the permission of the Turkish Government to introduce food stuff into Syria and Mt. Lebanon.

***

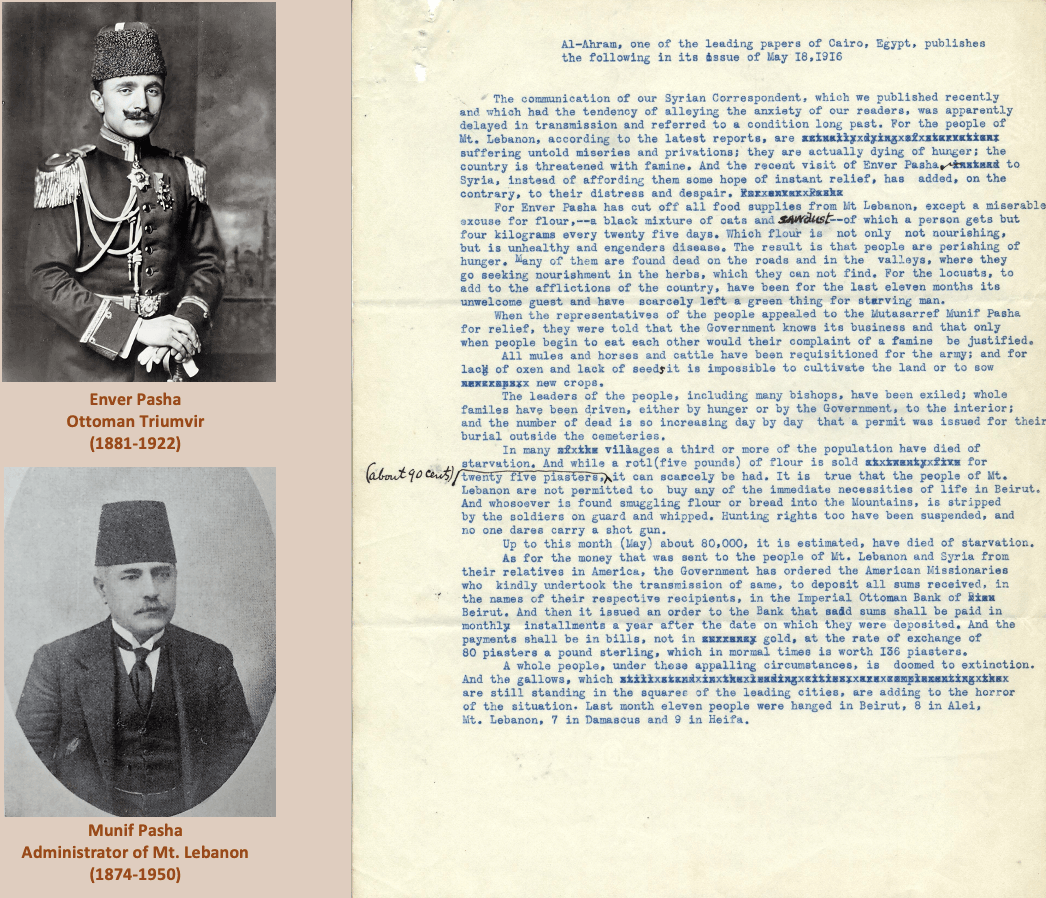

«Al-Ahram», one of the leading papers of Cairo, Egypt,[19] publishes the following in its issue of May 18, 1916.

The communication of our Syrian Correspondent, which we published recently and which had the tendency of allaying the anxiety of our readers, was apparently delayed in transmission and referred to a condition long past. For the people of Mt. Lebanon, according to the latest reports, are suffering untold miseries and privations; they are actually dying of hunger; the country is threatened with famine. And the recent visit of Enver Pasha[20] to Syria, instead of affording them some hope of instant relief, has added, on the contrary, to their distress and despair.

For Enver Pasha has cut off all food supplies from Mt. Lebanon, except a miserable excuse for flour, – a black mixture of oats and sawdust – of which a person gets but four kilograms every twenty-five days. Which flour is not only not nourishing, but is unhealthy and engenders disease. The result is that people are perishing of hunger. Many of them are found dead on the roads and in the valleys, were they go seeking nourishment in the herbs, which they cannot find. For the locusts, to add to the afflictions of the country, have been for the last eleven months its unwelcome guest and have scarcely left a green thing for starving man.

When the representatives of the people appealed to the Mutasarrif Munif Pasha for relief, they were told that the Government knows its business and that only when people begin to eat each other would their complaint of a famine be justified.

All mules and horses and cattle have been requisitioned for the army; and for lack of oxen and lack of seeds it is impossible to cultivate the land or to sow new crops.

The leaders of the people, including many bishops, have been exiled; whole families have been driven, either by hunger or by the Government, to the interior; and the number of dead is so increasing day by day that a permit was issued for their burial outside the cemeteries.

In many villages a third or more of the population have died of starvation. And while a rotl (five pounds) of flour is sold for twenty-five piasters [about 90 cents], it can scarcely be had. It is true that the people of Mt. Lebanon are not permitted to buy any of the immediate necessities of life in Beirut. And whosoever is found smuggling flour or bread into the Mountains, is stripped by the soldiers on guard and whipped. Hunting rights too have been suspended, and no one dares carry a shot gun.

Up to this month (May) about 80,000, it is estimated, have died of starvation.

As for the money that was sent to the people of Mt. Lebanon and Syria from their relatives in America, the Government has ordered the American Missionaries who kindly undertook the transmission of same, to deposit all sums received, in the names of their respective recipients, in the Imperial Ottoman Bank of Beirut. And then it issued an order to the Bank that said sums shall be paid in monthly installments a year after the date on which they were deposited. And the payments shall be in bills, not in gold, at the rate of exchange of 80 piasters a pound sterling, which in normal times is worth 136 piasters.

A whole people, under these appalling circumstances, is doomed to extinction. And the gallows, which are still standing in the squares of the leading cities, are adding to the horror of the situation. Last month eleven people were hanged in Beirut, 8 in Aley, Mt. Lebanon,[21] 7 in Damascus and 9 in Haifa.

***

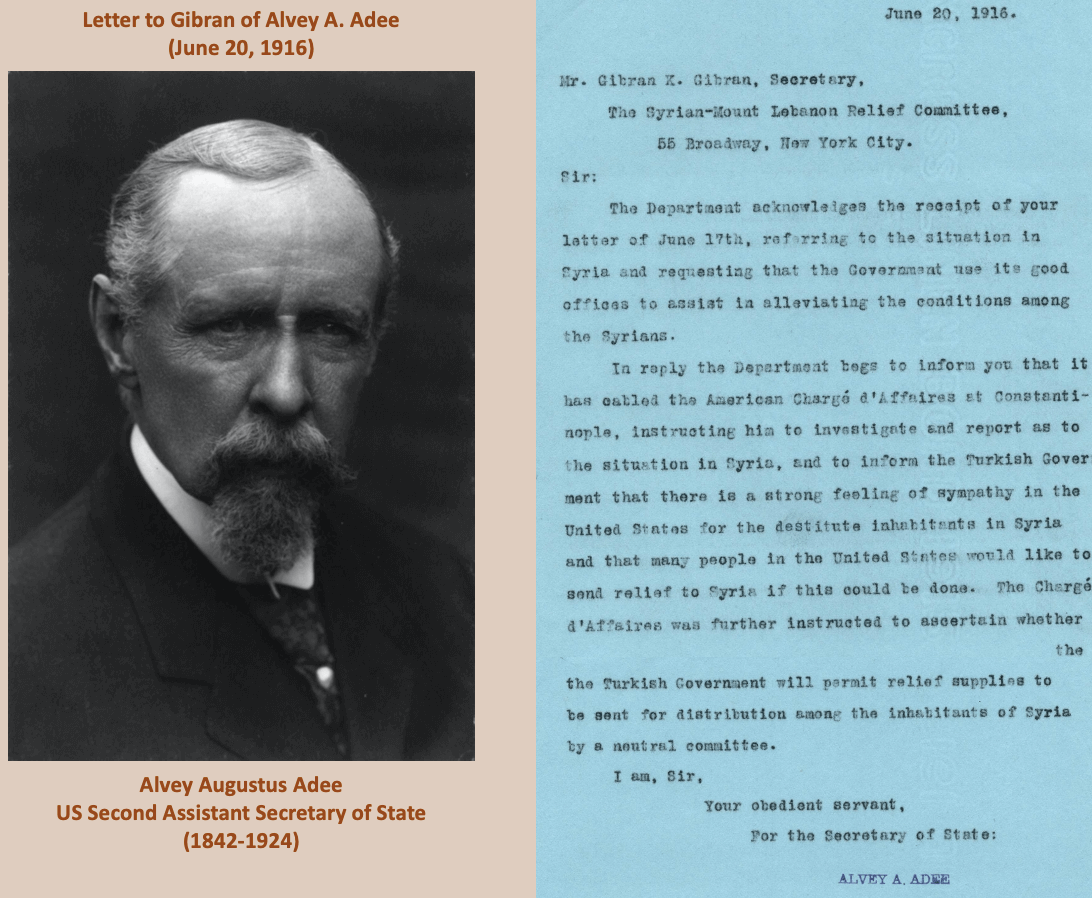

Three days later, Alvey Augustus Adee (1842-1924), US Second Assistant Secretary of State, replied Gibran’s letter as follows:

***

June 20, 1916

Mr. Gibran K. Gibran, Secretary.

The Syrian-Mount Lebanon Relief Committee,

55 Broadway, New York City.

Sir:

The Department acknowledges the receipt of your letter of June 17th, referring to the situation in Syria and requesting that the Government use its good offices to assist in alleviating the conditions among the Syrians.

In reply the Department begs to inform you that it has cabled the American Chargé d’Affaires at Constantinople, instructing him to investigate and report as to the situation in Syria, and to inform the Turkish Government that there is a strong feeling of sympathy in the United States for the destitute inhabitants in Syria and that many people in the United States would like to send relief to Syria if this could be done. The Chargé d’Affaires was further instructed to ascertain whether the Turkish Government will permit relief supplies to be sent for distribution among the inhabitants of Syria by a neutral committee.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

For the Secretary of State:

Alvey A. Adee

Second Assistant Secretary.[22]

***

On July 7, Gibran wrote to Mary that his energies were being completely absorbed by his relief work, but his words seem to reveal a certain optimism:

“On Friday and Saturday, I must go down to the office of the committee like any other day. […] In these days […] I am really nothing but the secretary of a relief committee. I cannot think thoughts nor can I dream dreams. Even my imagination is asleep – and every day I come home so tired that I cannot even sleep. But I am well, and everything is going well.”[23]

In truth, from a letter he sent to Ameen Rihani in the same days, we learn that the work was not without conflicts, inside and outside the Committee. In addition, although the suffering in Mount Lebanon was terrible, many Syrians in America displayed an apathy that infuriated Gibran:

“The situation here increases in confusion daily, and my patience has reached its limit, for I am among a people whose language I do not understand and who do not understand mine. Ameen Saliba has tried to annex the Philadelphia Committee to his own, and he might succeed. Nami Tadross never comes to this office and does not sign the receipts! Najeeb Shaheen [Maloof] has formally resigned, and I am trying to placate him with all the proofs I have at hand. Najib Kasbani is overwhelmed and doesn’t know what he’s doing. Mr. Dodge informed us that he’s going to the country and asked us to meet with Mr. Scott. The city Mayor[24] cannot give us permission for a tag day. As for the Syrians here, they are even stranger than they used to be – the leaders grow in their leadership while the gossip-mongers intensify their gossip-mongering. All these matters, Ameen, have led me to hate life and had it not been for the cries of the hungry which fill my heart, I would not have spent a minute longer in this office nor an hour longer than I should have in this city. Tomorrow evening, we shall meet and present to the Committee the matter of contributions to the American Committee [for Armenian and Syrian Relief]. I swear by God, Ameen, that it would be better to share the deprivation of the hungry and the suffering of the afflicted; and if I were to choose between death in Lebanon or life among these creatures, I would choose death.”[25]

Said divisions and disagreements within the Syrian-Mount Lebanon Relief Committee led to the formation of a new board: Najib Kasbani (Naǧīb Kasbānī), chairman; Ameen Rihani and Shoukri Rhayem (Šukrī Raḥayyim), vice chairmen; Nami Tadross, Danielle Faour (Dānīāl Fā‘ūr), Youssef Bek Mouoshi (Yūsuf Bik Mu‘ūšī), Kaleel Teen and Ghatas Fares (Ġaṭās Fāris), treasurers; Gibran was confirmed as secretary.[26] As for the former chairman Najeeb S. Maloof, he would get killed in a tragic accident on September 5.[27] In a letter to Mary Haskell dated August 22, Gibran said how worn-out he was, confirmed that the Turkish government, as expected, had refused to allow Relief in Syria, and announced that he would go on vacation at Cohasset for a period of rest:

“It has been extremely hot here – and it is still hot – and I am weary physically, but the spirit is yet willing. Somehow, I cannot make myself go away, but I shall have to, and very soon, too. I need the change very badly. When you are working on a relief committee, you become drunk with something sweeter and dearer than comfort. Every dollar you receive brings with it a little breath of life, and you feel strangely soft and tender in your inside. I am sure you know what it is. Yes, Turkey refused to allow Relief in Syria. But we can send money to be distributed amongst the needy. It is true that harvests are very good this year – thanks be to God – but there is a bitter need for money. The Americans in Syria are able to distribute whatever we can send them. The American government can do much if it chooses. But to choose the hardest way (and the hardest way is usually the right way) is to be superhuman in this age of local interests, local desires and local righteousness. However, Mr. Elkus, the new ambassador to Turkey,[28] promised to do many good things for us before he sailed. He left this city for his post about a week ago. […] If things go well during this week down in the office, I will be able to go to Cohasset for a week or ten days. I might go Monday or Tuesday of next week. But I am never certain – You know how it is, Mary.”[29]

Gibran escaped the city and went with Marianna to Cohasset early in September. This time, he had accepted an invitation to stay at the summer house of his friend Julia Manning, a Boston society lady, at 53 Bow Street. Unfortunately, all those months of hard work had severely prostrated him. In a letter sent from Cohasset to the poet Witter Bynner (1881-1968) on September 22, he acknowledged his poor health: «I am ill in bed. I came to Cohasset about two weeks ago with the wingless body and a weary soul – and now my sister and a good doctor are taking care of me». Several days later, in another undated letter to him, Gibran described more precisely what seemed to be a psychosomatic ailment: «It is a nervous breakdown. Overwork and the tragedy of my country brought a cold, dull pain to my left side, face, arm and leg».[30] On September 14, he had received the following letter from Rihani about alternative solutions to circumvent the ban from Turkey and deliver aid in Syria:

“Dear Gibran: Yesterday, when I came back from the mountain region [in New York State], I received your letter, whose news displeased me. I hope you are better now, so you may return to us after completely recovering. Do not worry, my brother, about the unfinished work; had our efforts to do our work been as well pursued as our goals, we all would have been amongst the most joyful and honored. (You know whom I mean by all). How great it is to say that we work in a committee that does not enjoy the confidence of the Syrians living inland [in the USA]. Still, I am persistent in my work; but I would have preferred to hear you recount what you were doing during your absence. However, you should not get the impression that I have a lot of work, much less any significant work, to do in the office nowadays. But our committee intends to hold a meeting next Tuesday to decide on sending the money through governmental officials, when our friend and his party demand the money be sent directly to the Maronite Patriarch. By Tuesday, I hope you will have completely recovered and can attend the meeting; then, you could help us support what is legitimate and cast-off what is not. All our brothers send you their greetings, especially Najib Kasbani, who has just arrived. May the Lord grant you both good health and energy so you may join us soon.”[31]

With events getting worse every day in Syria, and the Turks flagrantly violating any human rights, Gibran’s life would undoubtedly have been in grave danger had he returned to his homeland. But even in America there were dangers. Moreover, also his relationships with Rihani were deteriorating, as we learn from Mary Haskell’s journal dated October 5:

“Turkish spies are, of course, watching everything that is done here. […] I can’t get away from Syria; I never shall; I am a Syrian… and yet this work is almost more than I can bear. Rihani – and all the others – they understand one another so well… but I don’t understand them, and they don’t understand me… they say, «O, you just come down there and sit, and all will be well» – they are taking care, as it were, of the bird that lays golden eggs… I can get money when no one else can. Because the work of Turkey has been to divide those she governs – the Syrians do not trust one another. They fear that if they give money to the Committee the money, it won’t reach those who are suffering in Syria… I have to talk to all these people to explain, to convince them… I can make them weep – and they do what I ask them to… Spies watched the Committee’s every movement in New York, and if any Syrian in the U.S. displeases Turkey, his relatives are killed. That is why the U.S. Syrians are so infinitely cautious and watchful.”[32]

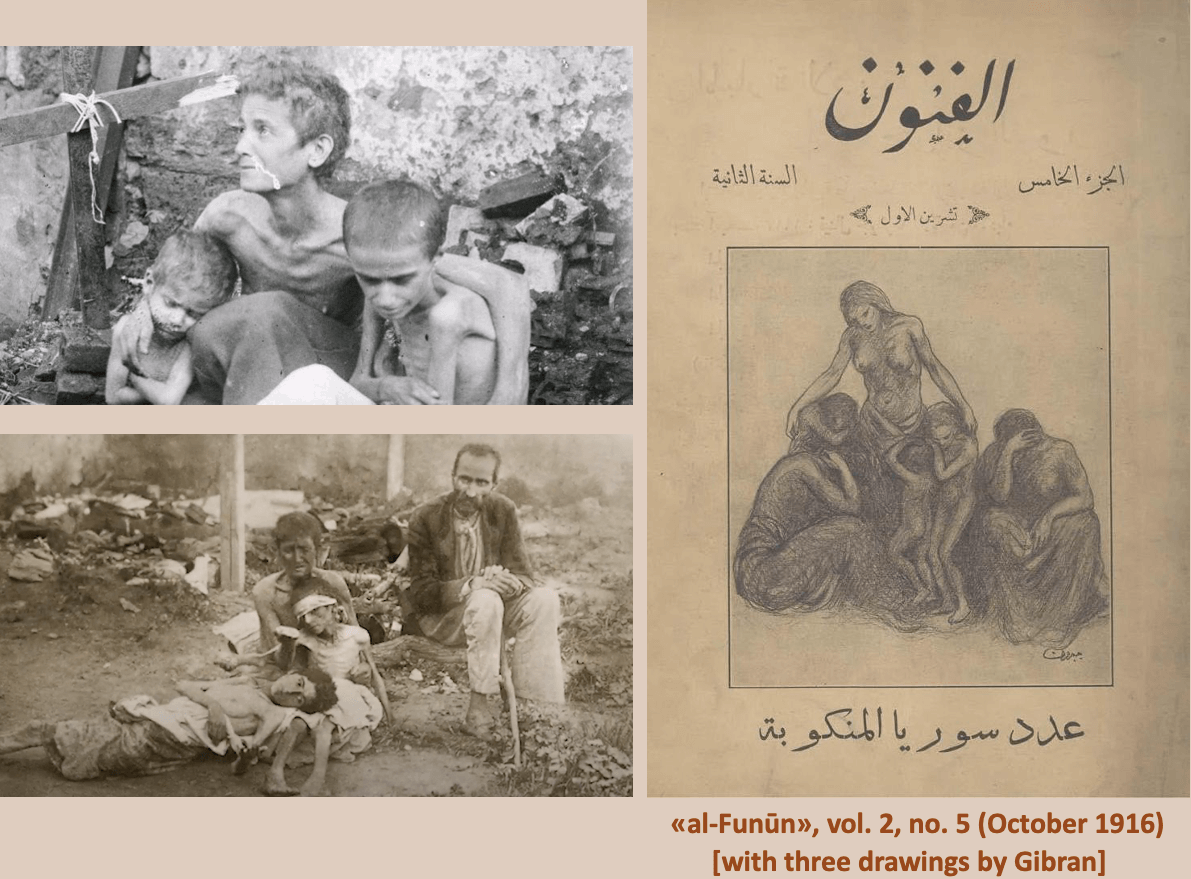

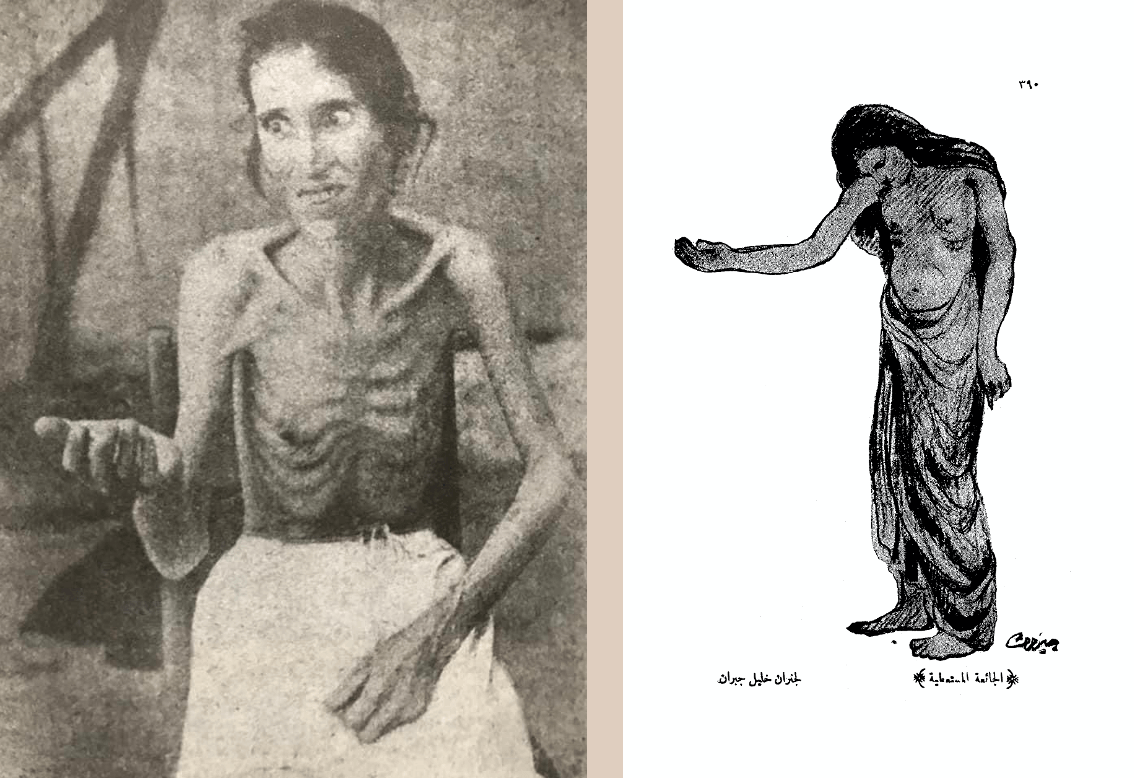

In that same October, a special issue of the Arab-American monthly «al-Funūn» (or «Al-Funoon», ‘The Arts’ in Arabic) on the Syrian crisis with the title ‘Adad Sūriyā al-Mankūbah (An Issue on Stricken Syria) appeared in New York. Contributions to it included, among others, the short story Mahraǧān al-Mawt (Festival of Death) by Mikhail J. Naimy (Mīḫā’īl Yūsuf Nu‘aymah, 1889-1988), the essay al-Ǧaw‘ (The Hunger) by Ameen Rihani, the poem Fī al-Layl (To the Night) by Elia Abu Madi (Īlīyā Abū Māḍī, 1890-1957), also known as Elia D. Madey. Gibran contributed three drawings (the cover illustration, untitled, representing a starving family; a sketch entitled al-Ǧā’i‘ah al-Musta‘ṭiyyah [The Starving Beggar Woman];[33] and a profile of his mother Kamila Rahme [Kāmilah Raḥmah, 1858-1904], captioned Waǧh Ummī Waǧh Ummatī [My Mother’s Face is My Nation’s Face], accompanied by an editorial statement of mobilization that read: «This is a word born from the heart of Gibran. It is incumbent upon us, every Syrian, to adopt it like a constitution – to give a purpose in these days brimming with strife and adversity»[34]) and the poem Māta Ahlī[35] (Dead Are My People). It begins with an elegy dedicated to the victims of the genocide in Syria, then moves into a self-condemnatory mood before concluding with a touching appeal to his fellow exiles to support the relief effort:

Dead Are My People

(Written in exile during the famine in Syria)

“WORLD WAR I”

Gone are my people, but I exist yet,

Lamenting them in my solitude…

Dead are my friends, and in their

Death my life is naught but great

Disaster.

The knolls of my country are submerged

By tears and blood, for my people and

My beloved are gone, and I am here

Living as I did when my people and my

Beloved were enjoying life and the

Bounty of life, and when the hills of

My country were blessed and engulfed

By the light of the sun.

My people died from hunger, and he who

Did not perish from starvation was

Butchered with the sword; and I am

Here in this distant land, roaming

Amongst a joyful people who sleep

Upon soft beds, and smile at the days

While the days smile upon them.

My people died a painful and shameful

Death, and here am I living in plenty

And in peace... This is deep tragedy

Ever-enacted upon the stage of my

Heart; few would care to witness this

Drama, for my people are as birds with

Broken wings, left behind the flock.

If I were hungry and living amid my

Famished people, and persecuted among

My oppressed countrymen, the burden

Of the black days would be lighter

Upon my restless dreams, and the

Obscurity of the night would be less

Dark before my hollow eyes and my

Crying heart and my wounded soul.

For he who shares with his people

Their sorrow and agony will feel a

Supreme comfort created only by

Suffering in sacrifice. And he will

Be at peace with himself when he dies

Innocent with his fellow innocents.

But I am not living with my hungry

And persecuted people who are walking

In the procession of death toward

Martyrdom… I am here beyond the

Broad seas living in the shadow of

Tranquility, and in the sunshine of

Peace...I am afar from the pitiful

Arena and the distressed, and cannot

Be proud of aught, not even of my own

Tears.

What can an exiled son do for his

Starving people, and of what value

Unto them is the lamentation of an

Absent poet?

Were I an ear of corn grown in the earth

Of my country, the hungry child would

Pluck me and remove with my kernels

The hand of Death from his soul. Were

I a ripe fruit in the gardens of my

Country, the starving woman would

Gather me and sustain life. Were I

A bird flying the sky of my country,

My hungry brother would hunt me and

Remove with the flesh of my body the

Shadow of the grave from his body.

But, alas! I am not an ear of corn

Grown in the plains of Syria, nor a

Ripe fruit in the valleys of Lebanon;

This is my disaster, and this is my

Mute calamity which brings humiliation

Before my soul and before the phantoms

Of the night... This is the painful

Tragedy which tightens my tongue and

Pinions my arms and arrests me usurped

Of power and of will and of action.

This is the curse burned upon my

Forehead before God and man.

And oftentimes they say unto me,

“The disaster of your country is

But naught to the calamity of the

World, and the tears and blood shed

By your people are as nothing to

The rivers of blood and tears

Pouring each day and night in the

Valleys and plains of the earth…”

Yes, but the death of my people is

A silent accusation; it is a crime

Conceived by the heads of the unseen

Serpents... It is a songless and

Sceneless tragedy... And if my

People had attacked the despots

And oppressors and died as rebels,

I would have said, “Dying for

Freedom is nobler than living in

The shadow of weak submission, for

He who embraces death with the sword

Of Truth in his hand will eternalize

With the Eternity of Truth, for Life

Is weaker than Death and Death is

Weaker than Truth.

If my nation had partaken in the war

Of all nations and had died in the

Field of battle, I would say that

The raging tempest had broken with

Its might the green branches; and

Strong death under the canopy of

The tempest is nobler than slow

Perishment in the arms of senility.

But there was no rescue from the

Closing jaws… My people dropped

And wept with the crying angels.

If an earthquake had torn my

Country asunder and the earth had

Engulfed my people into its bosom,

I would have said, “A great and

Mysterious law has been moved by

The will of divine force, and it

Would be pure madness if we frail

Mortals endeavoured to probe its

Deep secrets…”

But my people did not die as rebels;

They were not killed in the field

Of battle; nor did the earthquake

Shatter my country and subdue them.

Death was their only rescuer, and

Starvation their only spoils.

My people died on the cross…

They died while their hands

Stretched toward the East and West,

While the remnants of their eyes

Stared at the blackness of the

Firmament... They died silently,

For humanity had closed its ears

To their cry. They died because

They did not befriend their enemy.

They died because they loved their

Neighbours. They died because

They placed trust in all humanity.

They died because they did not

Oppress the oppressors. They died

Because they were the crushed

Flowers, and not the crushing feet.

They died because they were peace

Makers. They perished from hunger

In a land rich with milk and honey.

They died because the monsters of

Hell arose and destroyed all that

Their fields grew, and devoured the

Last provisions in their bins…

They died because the vipers and

Sons of vipers spat out poison into

The space where the Holy Cedars and

The roses and the jasmine breathe

Their fragrance.

My people and your people, my Syrian

Brother, are dead… What can be

Done for those who are dying? Our

Lamentations will not satisfy their

Hunger, and our tears will not quench

Their thirst; what can we do to save

Them from between the iron paws of

Hunger? My brother, the kindness

Which compels you to give a part of

Your life to any human who is in the

Shadow of losing his life is the only

Virtue which makes you worthy of the

Light of day and the peace of the

Night… Remember, my brother,

That the coin which you drop into

The withered hand stretching toward

You is the only golden chain that

Binds your rich heart to the

Loving heart of God…[36]

In that summer of 1916, the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief had begun raising funds for a ship to bring supplies to Beirut. The campaign attracted tremendous support amongst the American public, and a ship, the US Naval collier Caesar, was loaded with $700,000-worth of relief supplies, as follows:

On November 5, Gibran shared the good news with Mary Haskell:

“The Committee work is going on wonderfully. I have had nothing else in my life but the constant desire to make things go well – and they are going well. The United States Navy has granted us a steamer which we, in cooperation with American Red Cross Society, are trying to fill with foodstuffs, medicines and other necessities. The American Committee has been very generous – and I think that no less than 750 thousand dollars-worth of things will be shipped. All this, Mary, means work, work, work night and day. But it is by far the best work I have done in my life. And I have been in a hurry – always in a hurry – since I came back from Cohasset. Never have I been so conscious of Time – and the desire of not losing a minute has been upon me and within me. To lose a minute in a relief work is to lose a chance, and one cannot lose a chance of any sort when the cries of thousands of sufferers are filling your soul. But oh, how wonderful it is to be in a hurry: it makes one feel like beating wings.”[38]

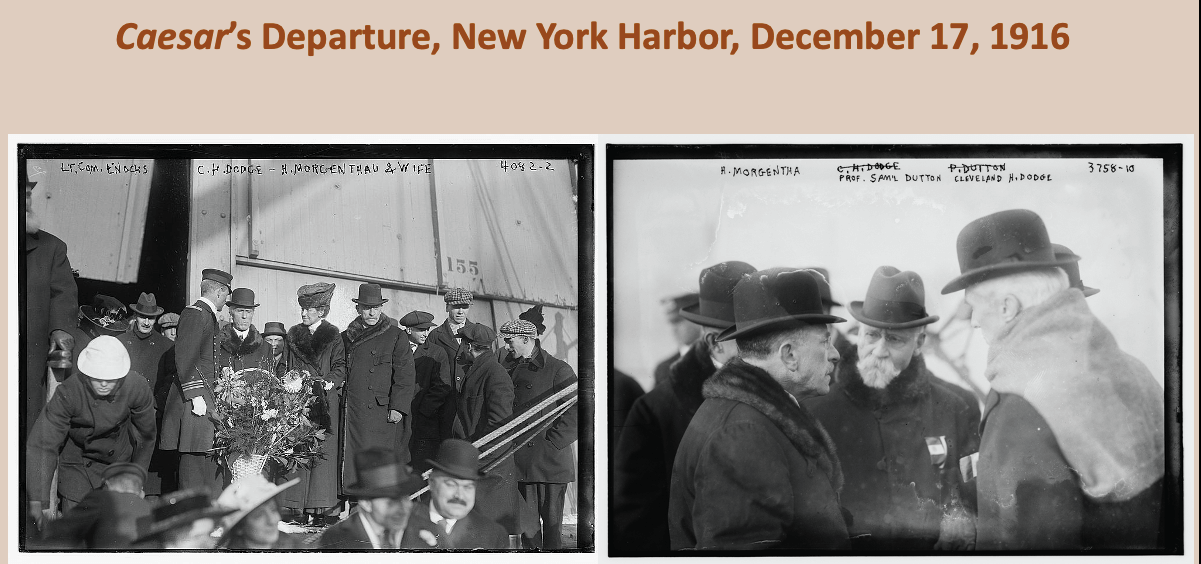

Throughout all the weeks before the Caesar sailed, Gibran continued to work indefatigably, as he wrote to Mary on November 7: «I go to the office of the Committee every morning as early as possible in these days – and I fear that I must go on Friday morning as well. […] We are trying to get the Syrian Bazar. Sunday is always a good day for such work».[39] The ship departed from the New York harbor on December 17, with the permission to disembark in Beirut at the end of the same month. Due to its gift cargo and expected arrival date, it was dubbed “the Christmas Ship”. Some official photos show, gathered on the dock, Lt. Commander John Matt Enochs (1878-1932), captain of the Caesar, Cleveland H. Dodge, Samuel T. Dutton, Henry Morgenthau and his wife Josephine Sykes Morgenthau (1863-1953).

In his authoritative biography of Gibran, Suheil B. Bushrui (Suhayl Badī‘ Bušrū’ī, 1929-2015) suggests that this was an affair with a happy ending: «After a hectic few weeks, the committee’s dreams were realized when the Caesar sailed for Syria».[40] But things turned out differently: the steamer never reached Beirut. It languished for months at a dock in Alexandria, Egypt, without permission from the Ottoman authorities to proceed. From a letter to Mary dated February 9, 1917, we can read all of Gibran’s deep and bitter disappointment: «News from Syria and Mt. Lebanon are more than one can bear. A group of young people – Syrians – will meet tomorrow evening in this studio to talk about things. […] It all seems like one long, black dream – and sometimes I feel quite lost».[41]

As for the fate of the cargo aboard the Caesar, some was damaged during its voyage from New York, some was sold in Alexandria, and some was sent to Salonika, Greece. Syria and Mount Lebanon saw nothing from the shipment. However, such a failure did not prevent Gibran from being an active member of other political organizations, such as the Syrian-Mount Lebanon Volunteer Committee, the Syria-Mount Lebanon League of Liberation (also known as the Syrian-Lebanese League of Liberation) and the Syrian-Lebanese League of North America, all founded in New York in 1917 (after American entry into World War I in April of the same year) by his friend Eyyoub George Tabet (Ayyūb Ǧirǧis Tābit, 1875-1947), a Lebanese Protestant politician and physician, whose aim was that of encouraging young Syrian-Lebanese-Americans to bear arms against Turkey for Middle Eastern autonomy. Gibran was well aware of the danger he was putting himself in, as can be read in Mary Haskell’s journal dated December 26, 1917:

“«I know I’m of use because a new price has been set on my head – not that I mind that… The other day a letter was sent to me – anonymous – and a similar one to Doctor Tabet in English. ‘Turkey is not dead – and she has a long arm – If you do not stop what you are doing–’ (I forgot the closing threat, [interpolated Mary] but the sense was you’ll soon not be alive to do it – and the usual blood-dripping dagger was added). Of course… I know that if the agents of Turkey were really planning to kill me in New York, they wouldn’t say anything about it – but just the same, I made use of that letter; I telephoned straight to the Department of Justice».[42] […] He showed me the scar on his arm that a shot in Paris had given him – a Turkish attempt on his life… He had never told me of that before – the shot was fired too close – and had been a failure. But threats and plots do not affect him. It is the non-personal things that he thinks about and worries over.”[43]

Gibran could not imagine then that even in the USA, his activism would be observed with suspicion and that new enemies were lurking around him.[44]

* This article is based on an excerpt from the paper: F. Medici, Kahlil Gibran between the Great Famine of Mt. Lebanon and the First Red Scare in the USA. Unpublished and Secret Documents, «Mirrors of Heritage», Special Issue – Centennial of The Prophet, Lebanese American University (LAU), September 2023, pp. 176-225.

[1] Around 200,000 people died when the population of Mount Lebanon was estimated to be 400,000 people.

[2] Suheil Bushrui & Joe Jenkins, Kahlil Gibran: Man and Poet. A New Biography, Oxford-Boston: Oneworld, 1998, p. 154.

[3] The Letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell. Visions of Life as Expressed by the Author of “The Prophet”, arranged and edited by Annie Salem Otto, Houston: Smith & Company Compositors – Southern Printing Company, 1970, pp. 438-439.

[4] Ǧubrān Ḫalīl Ǧubrān, Kitāb Dam‘ah wa Ibtisāmah, New York: Maṭba‘at al-Atlantīk, 1914.

[5] Otto, pp. 479-480.

[6] Otto, p. 481.

[7] Otto, pp. 484-485.

[8] Otto, pp. 485-486.

[9] Bushrui & Jenkins, p. 158.

[10] Otto, p. 487.

[11] A vilayet (meaning «province» in Ottoman Turkish) was a first-order administrative division of the later Ottoman Empire.

[12] Cf. Watson E. Mills & Roger Aubrey Bullard, Mercer Dictionary of the Bible, Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1990, p. 508: «The Lebanons are the most western mountain range parallel to the coastal plains adjacent to the Mediterranean Sea. The Anti-Lebanons are further to the east, roughly parallel to the Lebanons».

[13] «Mir’āt al-Ġarb» (or «Meraat-ul-Gharb [‘Mirror of the West’] – “The Daily Mirror”»), founded in New York by Najeeb M. Diab (Naǧīb Mūsá Diyāb, 1870-1936) in 1899.

[14] The inhabitants of ‘Ašqūt (also spelled Ashqout or Achqout), located 31 kilometers north of Beirut, were and are predominantly Maronite Catholic, with Christians from other denominations in the minority.

[15] Yūsuf Bišārah al-Hānī (sometime anglicized as Joseph Hani) was a Maronite resident of Beirut. In March 1913, he was one of six men who had signed a letter to the French consul in Beirut, François Georges-Picot (1870-1951), requesting French assistance to liberate Syria and Mount Lebanon from the rule of the Ottoman Empire. He was publicly hanged by Turks for high treason on April 5, 1916, at al-Burǧ (or, ‘The Tower,’ the main square now known as Martyrs’ Square), in Beirut, at 5 am on April 5, 1916. His name, together with the names of other Syrian and Lebanese nationalists executed, is commemorated every year on May 6 during Martyrs’ Day in modern-day Lebanon and Syria.

[16] Elias Huwayyik (Īlyās Buṭrus al-Ḥuwayyik, 1843-1931).

[17] Hussein Kamel (Husayn Kāmil, 1853-1917) was the Sultan of Egypt from 1914 to 1917 during the British protectorate.

[18] Pope Benedict XV (Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, 1854-1922).

[19] The editor-in-chief of the daily newspaper «al-’Ahrām» (‘The Pyramids’) was then Daud Barakat (Dāwūd Barakāt, 1868-1933), a Lebanese writer and journalist.

[20] İsmail Enver Paşa (1881-1922) formed one-third of the dictatorial triumvirate known as the ‘Three Pashas’ (along with Talaat Pasha [Mehmed Talat Paşa, 1874-1921] and Djemal Pasha) in the Ottoman Empire.

[21] The city of ‘Alayh (literally, ‘high place’ in Arabic) is located 15 km uphill from Beirut on the freeway to Damascus. It was the place where Djemal Pasha executed a large number of Lebanese and Syrian Arab nationalists who sought independence from the Ottomans.

[22] The U.S. National Archives (USNA); Record Group 59: General Records of the Department of State; 1910-29 Central Decimal File; File: 867.48/306

[23] Otto, p. 489.

[24] John Purroy Mitchel (1879-1918) was the mayor of New York from 1914 to 1917.

[25] Correspondence between Gibran and Rihani, in Excerpts from Ar-Rihaniyat by Ameen Rihani, edited with an introduction by Naji B. Oueijan, Beirut: Notre Dame University Press-Louaize, 1998, pp. 71-72. The letter is undated and written on the Syrian-Mount Lebanon Relief Committee’s official paper.

[26] As confirmed by a draft of a letter signed by Gibran himself written on the committee’s official paper to the president of the Syrian American Club of Boston asking him to support those affected by the famine in Mount Lebanon, dated July 28,1916, a document kept at the archives of the Arab American National Museum (AANM), Dearborn, MI, USA.

[27] Cf. Najib S. Maloof is Killed. New York Merchant Thrown from Auto in Tuxedo Park, «The New York Times», Sept. 6, 1916, p 6: «Tuxedo, N.Y., Sept. 5. – Najib S. Maloof a lace importer at 81 Rector Street, New York, died in the Tuxedo Hospital today an hour after he was injured in an automobile accident on the outskirts of Tuxedo Park».

[28] Abram Isaac Elkus (1867-1947) was the US ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople from October 2, 1916 to April 20, 1917.

[29] Otto, p. 495.

[30] Salim Mujais, The Face of the Prophet. Kahlil Gibran and the Portraits of the Temple of Arts, Beirut: Kutub, 2011, pp. 31-33.

[31] Correspondence between Gibran and Rihani, p. 74.

[32] Quoted in Jean Gibran & Kahlil G. Gibran, Kahlil Gibran: Beyond Borders, foreword by Salma Hayek-Pinault, Northampton (MA): Interlink Books, 2017, p. 263.

[33] The drawing illustrates mentioned Naimy’s short story describing a starving woman’s unsuccessful plea to a wealthy landowner.

[34] This English translation is quoted in Anneka Lenssen, Beautiful Agitation: Modern Painting and Politics in Syria, Oakland (CA): University of California Press, 2020, p. 63.

[35] «al-Funūn», vol. 2, no. 5 (October 1916), pp. 385-389.

[36] Kahlil Gibran, The Secrets of the Heart, Translated from the Arabic by Anthony Rizacallah Ferris and edited by Martin L. Wolf, New York: The Philosophical Library, 1947, pp. 187-197.

[37] Letter of the US Assistant Secretary of State William Phillips (1878-1968) to the Spanish Ambassador to the United States Juan Riaño y Gayangos (1865-1939), Washington, May 4, 1917 (Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1918, Supplement 2, The World War, Document 668, File No. 867.48/608).

[38] Otto, p. 501.

[39] Otto, p. 502.

[40] Bushrui & Jenkins, p. 160.

[41] Otto, p. 518.

[42] The Department was unable to help.

[43] Quoted in Jean Gibran & Kahlil Gibran, Kahlil Gibran: His Life and World, New York: Interlink Books, 1991, p. 306.

[44] Cf. Francesco Medici, “Suspected Bolsheviki” – The Classified FBI (BOI) File on Kahlil Gibran, Kahlil Gibran Collective, Jan 3, 2024 [https://www.kahlilgibran.com/latest/147-suspect-bolshevik-bureau-of-investigation-the-fbi-s-secret-files-on-kahlil-gibran.html].