All rights reserved. copyright 2024 © Glen Kalem-Habib

When we think of Kahlil Gibran’s artistry, it is a given to say that we define him through the lens of his much admired poetry above anything else. His timeless literary work, "The Prophet" supersedes even his principle expression as a visual artist; a body of work estimated at well over 700-800 pieces, all of which was refined primarily by his modality within the mediums of watercolour, oil, and graphite. And it is here, we further find another lesser-known facet of Gibran's craft that deserves our attention: his remarkable talent as a portraitist.

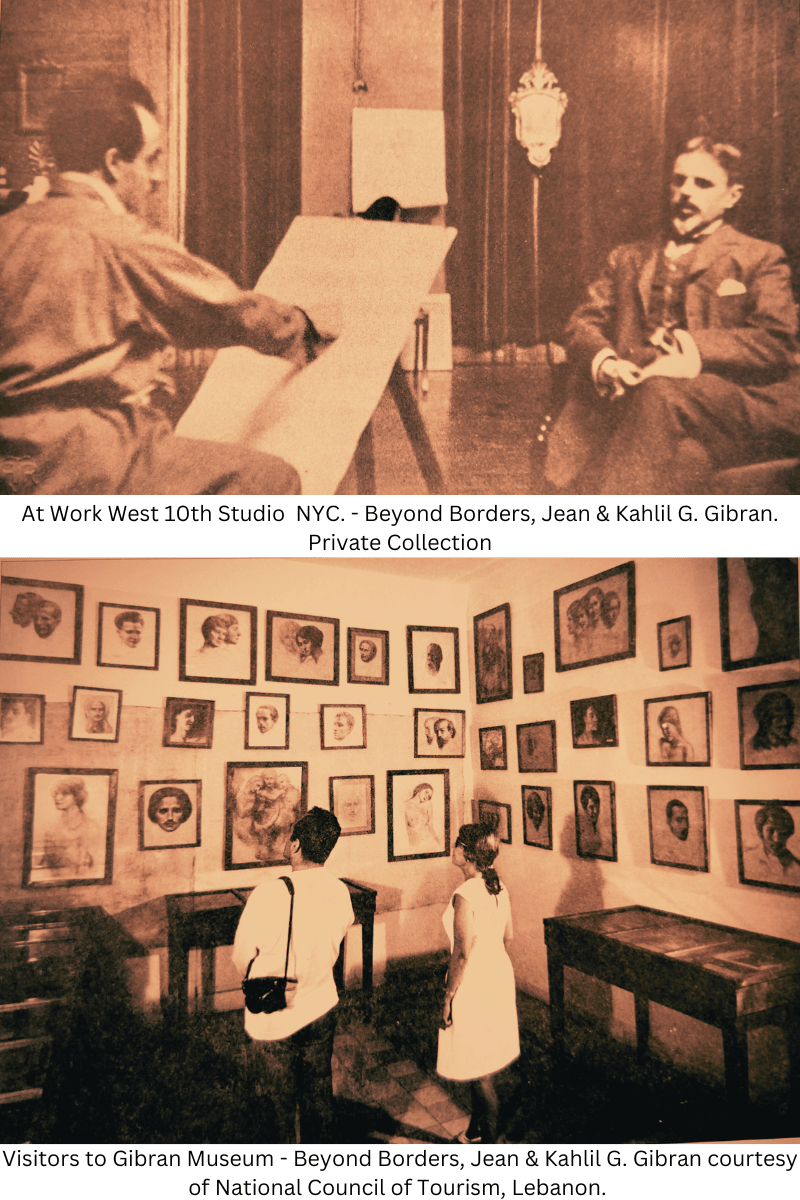

During his studentship in Paris between 1908 and 1911, Gibran began a project that would engage him for the remainder of his life. Dubbed the “Temple of Arts” series, this work went on to establish him as a sought-after portraitist among the global, cultural, and social elite. Surprisingly, this aspect of his artistic life remains somewhat concealed and limited to mainstream biographies and occasional art exhibitions. Furthermore, his work, if spoken about, is limited to only a handful of his most famous portraits, giving rise to the misconception that portraiture might have been a passing interest for him.

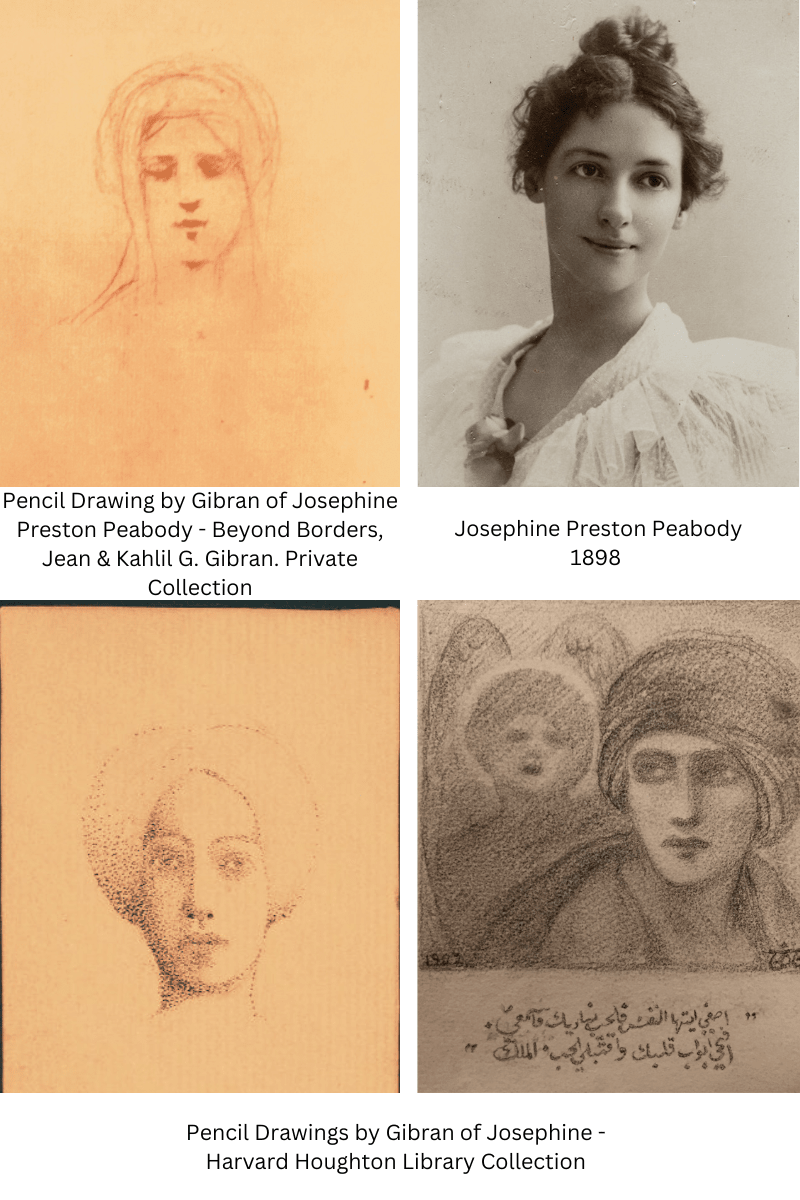

However, a deeper dive into Gibran's love for this craft reveals it started much earlier. An example of this can be observed in 1898, when he attempted to woo his first muse, Miss Josephine Peabody. The infatuated teenager sent her a drawing with a dedication in Arabic “to the esteemed Lady Josephine Peabody’

However, a deeper dive into Gibran's love for this craft reveals it started much earlier. An example of this can be observed in 1898, when he attempted to woo his first muse, Miss Josephine Peabody. The infatuated teenager sent her a drawing with a dedication in Arabic “to the esteemed Lady Josephine Peabody’

What this highlights is Gibran's connection with portraiture ran much deeper. It was a medium through which he connected with people on a personal level. The "Temple of Art" series would go on to feature portraits of individuals he encountered in his life's journey, including artists, thinkers, poets, and writers. One of these people was the sculptor Auguste Rodin, who introduced Gibran to William Blake's visionary works, sparking inspiration. This influence became pivotal in Gibran's creative journey. By 1914, this expression meant so much to him that, when it came to his very first public exhibition in New York, Gibran unveiled seventeen portraits of his "Temple of Art" series, a testament to his dedication to the craft.

What this highlights is Gibran's connection with portraiture ran much deeper. It was a medium through which he connected with people on a personal level. The "Temple of Art" series would go on to feature portraits of individuals he encountered in his life's journey, including artists, thinkers, poets, and writers. One of these people was the sculptor Auguste Rodin, who introduced Gibran to William Blake's visionary works, sparking inspiration. This influence became pivotal in Gibran's creative journey. By 1914, this expression meant so much to him that, when it came to his very first public exhibition in New York, Gibran unveiled seventeen portraits of his "Temple of Art" series, a testament to his dedication to the craft.

You might be surprised to learn that his portraits of poets and artists occasionally graced the pages of contemporary periodicals, contributing to his growing fame as a skilled portraitist and even making appearances in fictional narratives.

In a recent book by Salim Mujias the author captures for the first time a collection of about 50+ subjects, and the story behind them. For a more comprehensive story behind the work, this book is worth reading “Kahlil Gibran, Portraits”.

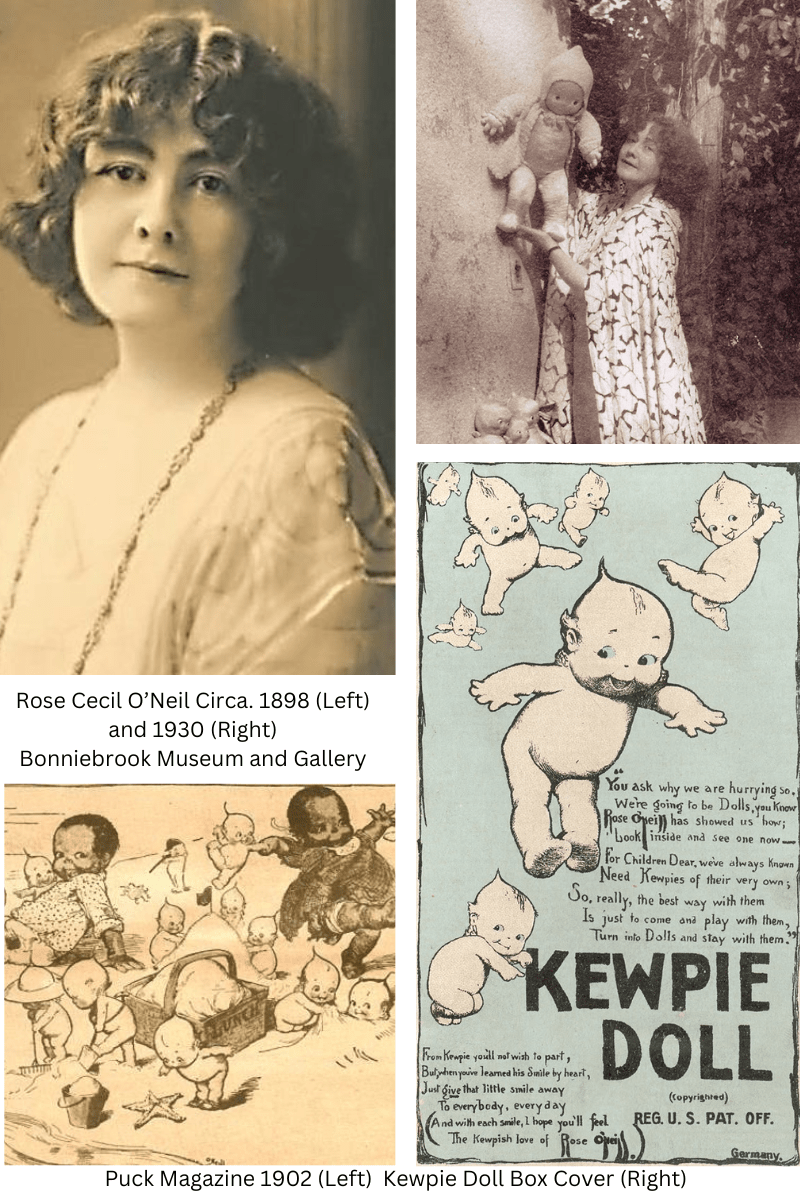

Yet, uncovering the full scope of Gibran's portraiture is an ongoing study. Mainstream biographies in the past have offered a deeper understanding, and tracing his activities through periodicals of the era has provided a great deal of information. While his correspondence with Mary Haskell provides some insight, it primarily serves as a list of names rather than a comprehensive exploration of his artistry. New portraits surface from time to time, and today we can reveal for the first time (on her birthday) a new portrait previously unknown to the collection, the portrait of Rose Cecil O'Neil (June 25th, 1874, April 6th, 1944)

Rose Cecil O'Neill was a trailblazing iconoclast who shattered gender barriers in the late 19th century. A self-taught artist, she defied societal norms to become a top illustrator, introducing the world to her creation, the Kewpie doll, and building an empire from it. Born in Pennsylvania in 1874 and raised in rural Nebraska, Rose's artistic talent emerged early, leading her to New York at just 18, where she rapidly rose to fame as a commercial illustrator, even becoming the first woman artist at Puck magazine.

Despite her commercial success, O'Neill never abandoned her creative pursuits, showcasing her work as a sculptor, painter, novelist, and poet. Her most iconic creation, "The Kewpies," began as a comic strip in 1909 and soon transformed into a global phenomenon with the release of Kewpie dolls in 1913. These dolls became the world's first novelty toy distributed worldwide, amassing her a considerable fortune.

With her newfound wealth, O'Neill lived lavishly in Castle Carabas, Connecticut, entertaining a diverse array of artists and guests. However, her generosity and extravagant lifestyle eventually led to financial hardships, and she passed away in 1944, penniless, in Missouri while working on her memoirs.

Despite her financial struggles in later life, O'Neill's legacy endured. The Kewpie doll remained an enduring symbol of American popular culture for over a century. Beyond her artistic contributions, Rose was also a vocal advocate for women's rights, participating in the suffrage movement and producing political cartoons and illustrations for the cause. She challenged societal norms by championing dress reform, rejecting corsets in favour of loose caftans.

Rose Cecil O'Neill's remarkable life story serves as a testament to her artistic innovation, entrepreneurial spirit, and unwavering commitment to advocating for women's rights, leaving an indelible mark on American culture that continues to resonate today.

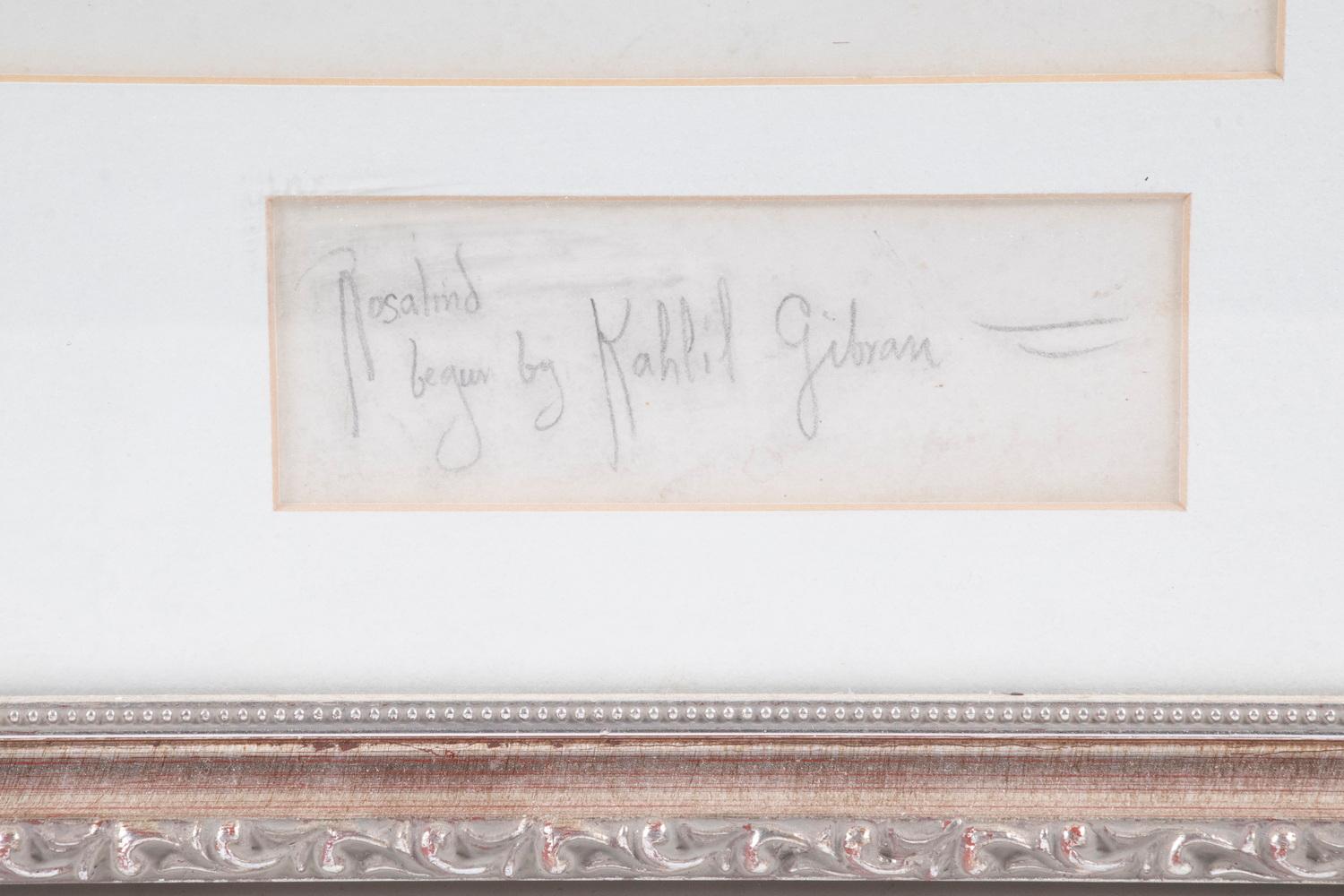

Little was known about the drawing until it popped up in an auction house in the MidWest states of the USA. Its provenance has some gaps, to be filled, but its authenticity is unquestionable. The delicate lines and evocative shading reveal Gibran's profound connection with his subjects, capturing not just her likeness but her artistic essence. The unknown about the drawing is the unfinished nature of it. As the unquestionable unique handwriting of Rose O’Neil states on the bottom of the drawing “Rosalind, Begun by Kahlil Gibran.

Who was 'Rosalind'? and why wasn't it completed, remian a mystery to be answered. Was Rosalind, Gibran's nickname for Rose? Was there a romantic fling? When the drawing was acquired its origins were traced to the MidWest state in Arkansas, which connects geographical with O’Neil’s, Bonniebrook Homestead home, where she lived out her last years after moving there from New York City. Notably, Rose O'Neil also portrayed Gibran in 1914, and intriguingly, similarities in the signatures suggest they have drawn each other- a testament to the artistic camaraderie of their time.

The date of the drawing is also unknown. Our guess would be it was made at the height of thier friendship between 1918-1922. Both, O'Neil and Gibran who were very active within the social movements of Greenwich Village, spent memorable nights at her Washington Square apartment, a gathering of 'theatrical utopia'.

Perhaps another clue to this drawing's date can be found in their fond memories together at Marie Garland's Buzzard Bay Farm retreat, where they were both frequent guests. In the spring of 1918, Kahlil accepted an invitation to retreat at the farm of Boston writer Marie Tudor Garland. Here, he enjoyed the luxury of working in his own private cottage. Marie, a widow of ten years, split her time between her Greenwich Village house, a place in New Hampshire, and her expansive Bay End Farm in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts.

She embraced the adventure of raising six children and her homes were always bustling with family, friends, and numerous artists. Marie's open-door policy made her a beloved host, especially among artists like Rose O'Neill, who cherished her vibrant gatherings.

During his stay, Kahlil wrote to Mary, sharing his excitement about his next project: "One large thought is filling my mind and my heart; and I want so much to give it form before you and I meet. It is to be in English—and how can anything of mine be really English without your help?" Over twenty-four days at Bay End Farm, he outlined and completed most of the first draft of this grand idea. Initially called *The Counsels*, it evolved into *The Prophet* by June 1919.

Letters from this retreat reveal Kahlil's contentment amidst the lively family and farm life. The retreat was a haven for creativity, and also for Rose O'Neill, her sister Callista, Indian activist and writer Dhan Gopal Mukerji, and his spouse, artist and painter Ethel Dugan.

Regardless of her mysterious orgins and unfinished nature, we are pleased to have her and look forward to exhibiting her alongside friends someday.

Sources and Acknowledgments:

Kahlil Gibran - Beyond Borders Jean and Kahlil G. Gibran Interlink Publishing 2017.

Kahlil Gibran Portraits - Salim Mujias Black House Publishing 2020.

Bonniebrook, Museum (Official)

The Prolific Illustrator Behind Kewpies Used Her Cartoons for Women’s Rights - Adina Solomon