This life-giving story about Elijah portrayed so powerfully by Ferdinand Bol reminds me of a short story by another artist, Lebanese born poet-artist Kahlil Gibran, titled The Tempest. In his story, a young man who is roaming the Cedar Forests of Lebanon gets caught in a terrible storm, and seeks cover in a cave inhabited by a hermit. And he sees his being caught in the storm as a fortunate opportunity, enabling him to visit this old hermit in his cave, as he has long wanted to learn this old man’s spiritual secrets. Upon being let in, when he complains about the tempest outside, the wise old man says to him, “The tempest is clean…why do you seek to escape from it?…" He then goes on to impart his wisdom to the young man, and near the end of the story, the old hermit declares, “I am going now to walk through the night with the tempest…it is a practice that I enjoy greatly…”. And then looking deeply into the young man’s eyes, he says, “I hope you will teach yourself to love the tempest.”

This life-giving story about Elijah portrayed so powerfully by Ferdinand Bol reminds me of a short story by another artist, Lebanese born poet-artist Kahlil Gibran, titled The Tempest. In his story, a young man who is roaming the Cedar Forests of Lebanon gets caught in a terrible storm, and seeks cover in a cave inhabited by a hermit. And he sees his being caught in the storm as a fortunate opportunity, enabling him to visit this old hermit in his cave, as he has long wanted to learn this old man’s spiritual secrets. Upon being let in, when he complains about the tempest outside, the wise old man says to him, “The tempest is clean…why do you seek to escape from it?…" He then goes on to impart his wisdom to the young man, and near the end of the story, the old hermit declares, “I am going now to walk through the night with the tempest…it is a practice that I enjoy greatly…”. And then looking deeply into the young man’s eyes, he says, “I hope you will teach yourself to love the tempest.”This is the lesson Elijah learned. His tempest allowed him to experience anew the beautiful presence and care of the Divine Artist, regardless of the strength of any of life’s storms.

Artworks in this Visual Meditation (in order of presentation):

- Ferdinand Bol, Angel Appearing to Elijah, 1642, Oil on canvas

- Marc Chagall, Elijah Touched by an Angel, 1930, Handcolored Etching-Ferdinand Bol, Elijah Resting under a Tree, ca. 1642, pen and brown ink

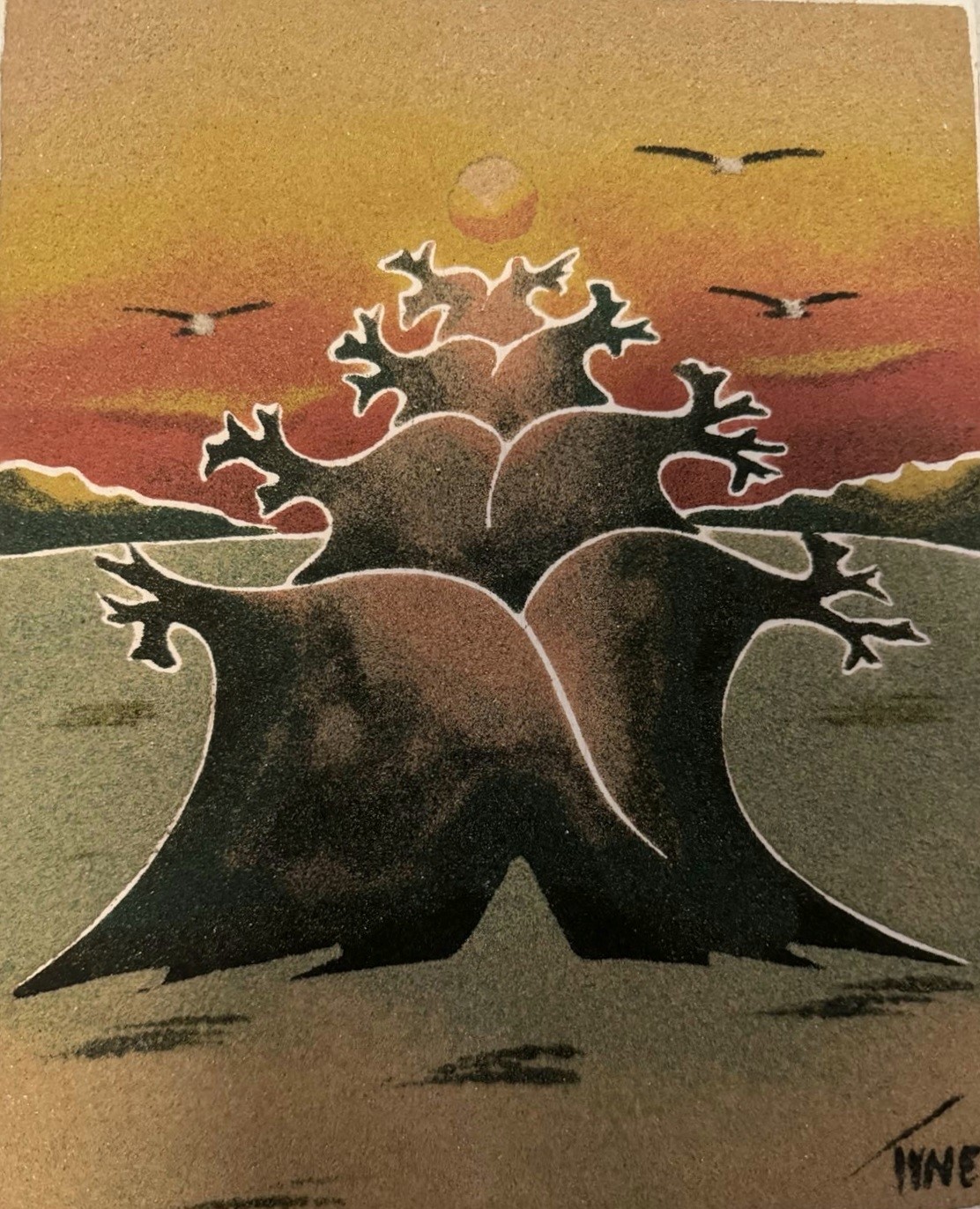

- Baobab Tree by Senegalese sand artist TINE, 2024, sand with Baobab tree glue on wood panel

- Kahlil Gibran, Self-portrait

Paul G. Chandler is an author, art curator, speaker, interfaith peacemaker, intercultural bridgebuilder and an authority on the Middle East and Africa. He grew up in Senegal, West Africa, and has lived and worked extensively around the world in senior leadership roles within publishing, the arts, relief and development and the Anglican Communion. As the Founding President of CARAVAN, he is recognized as a global leader in using the arts to further our quest for a more harmonious future, both with each other and with the earth, as well as in exploring the intersection between spirituality, faith and the arts. He is also a sought-after guide on the spirituality of the early 20th century poet-artist Kahlil Gibran, the author of The Prophet.

authority on the Middle East and Africa. He grew up in Senegal, West Africa, and has lived and worked extensively around the world in senior leadership roles within publishing, the arts, relief and development and the Anglican Communion. As the Founding President of CARAVAN, he is recognized as a global leader in using the arts to further our quest for a more harmonious future, both with each other and with the earth, as well as in exploring the intersection between spirituality, faith and the arts. He is also a sought-after guide on the spirituality of the early 20th century poet-artist Kahlil Gibran, the author of The Prophet.