-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

The Prophet of War

by Glen Kalem

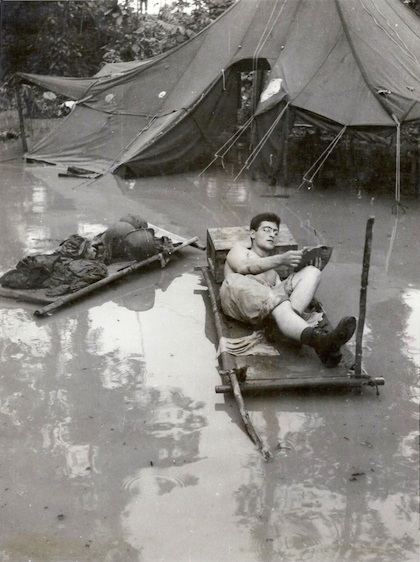

Picture this; you’re a combat soldier in WWII a few thousand miles away from home, hunched down in a murky bunker waiting for your orders to leap out onto the frontline of Normandy. Moreover, you’re the co-pilot flying a United States aircraft loaded with an atomic bomb en route to the Japanese city of Hiroshima… or further still, you’re one of the sixty-eight American servicewomen captured as a POW in the Philippines.

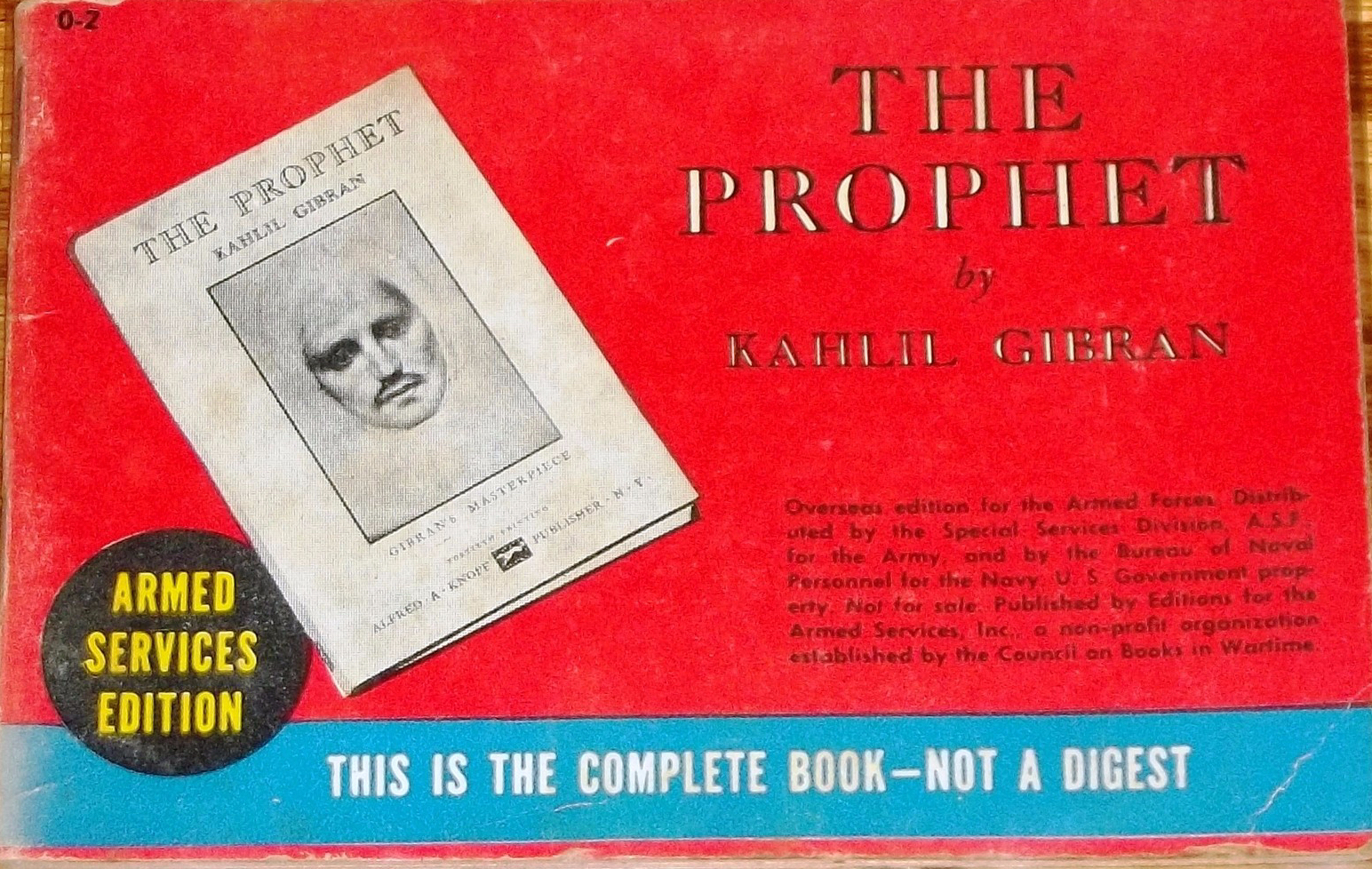

Packed in your uniform sits an oblong-shaped paperback – the front cover reads “Armed Services Edition” Next to it, a distinguished catchphrase “This is the complete book – not a digest”; in between is a photograph of the original book cover and an accompanying title with the author’s name, and the back cover features a glowing review of its contents and a brief biography of the author. The book you’re carrying is Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, you open up to the chapter on “Good and Evil” and read the opening passage:

“Of the good in you I can speak, but not of the evil. For what is evil but good tortured by its own hunger and thirst? Verily, when good is hungry it seeks food even in dark caves, and when it thirsts it drinks even of dead waters.”

As a researcher of Kahlil Gibran’s work and legacy for over two decades, I was astonished to find a copy of The Prophet reprinted and included in the “Armed Services Edition” ASE catalog. Of course, this opened up a can of worms, and I began a lengthy search to find what I could about this feat. The Prophet Armed Services Edition 1943

The Prophet Armed Services Edition 1943

How did the “Armed Services Edition” come about?

“Daniel J. Miller – Books Go to War, explains it as the following; “When the United States entered World War II in December of 1941, the Armed Services needed to do everything in their power to mobilize millions of ordinary American civilians to become physically fit, mentally awake, and high-spirited soldiers and sailors. Maintaining morale among the troops became a primary objective, and military officials realized that books could be instrumental in the process.”

Formed in 1942, the ASE saw a need to publish and distribute reading material in a compact and fresh format called paperback. This allowed for cost-effective printing and production at a fraction of the cost of hardbacks. Best of all, these slim, complete books were small enough for armed servicemen and women to carry during their time at war. The result was the birth of “The Armed Services Edition” library of books. Between 1943-1947 a series of 1322 books with varying titles were published. These included popular westerns, science fiction, and murder mysteries. Printed, published, and distributed, it’s believed that the ASE produced a staggering 123 million copies in its relatively short printing life. “Most ASE's were complete and unabridged reprints of their original texts.”

The result was the birth of “The Armed Services Edition” library of books. Between 1943-1947 a series of 1322 books with varying titles were published. These included popular westerns, science fiction, and murder mysteries. Printed, published, and distributed, it’s believed that the ASE produced a staggering 123 million copies in its relatively short printing life. “Most ASE's were complete and unabridged reprints of their original texts.”

Working closely with publishers, librarians, and booksellers, the Council on Books in Wartime agreed to organize and manage the project. Their task was to marshal the whole American book industry in favor of the project, and they succeeded. Set up as a non-profit organization, it did charge recuperation costs to cover the cost of printing and distribution. The Council drew up a set of recommendations that all participating publishers and authors abided by, making it fair game for all involved.

Most publishers agreed to a minimal royalties return, but most of them got involved as there was a sense of good reputation to have your book included in the illustrious ASE list.

Each month thirty to forty books would be selected by an advisory committee and reprinted as ASE editions. The books would be distributed free to Armed Services personnel with a wide selection of current publications and books of widespread popular appeal. In September 1943 the very first ASE to be printed was Leo Rosten’s collection of short stories – The Education of Hyman Kaplan.

The ASE selection committee chose writers who had earned a place within the literary canon, or who might reasonably be expected to do so, over time. The variety of books had the best of non-fiction and modern fiction alike. Authors such as Thomas Mann to John Steinbeck, Mark Twain, and Virginia Woolf. Genres such as humor, history, and science were also popular with titles such as Boris Sokoloff’s The Story of Penicillin.

How Gibran’s The Prophet got on this list is a question pending further research from his publisher Alfred Knopf. I’m on the case. The exact publishing and readership numbers of Gibran’s Prophet of War are hard to know, yet I could only imagine that the brave soldiers who did read it got some comfort from the book during their service. One can also conclude that whilst the selection of reading material was vast for such a small print run of four years, The Prophet was the only one included from an Arab-American.

Although he did not live to see it circulate, I’d imagine he would have taken comfort in knowing that his book was read on the battlegrounds, the same battlegrounds that overthrew the oppressive Turkish rule in his beloved Lebanon, a subject close to his heart. Gibran fought long and hard with his brush and pen for years to liberate the Levant.

In 1914 he published an “Open Letter to Islam” calling on the various native sects in Ottoman-occupied lands to cease their internecine struggles and unite in opposition to the Turks, as well as writing other articles highlighting the plight of his people and appealing for aid. He also helped organize a League of Liberation and was instrumental in the formation of a relief committee which raised funds to combat the famine that was sweeping the Middle East during those terrible years.

In 1921 he also wrote an essay, which due to one overstated translations from Arabic, was manipulated to be synonymously linked to the famous “ask not” speech of JFK. The essay first translated in 1958 entitled ”The New Era” reads as follows:

“Are you a politician who says to himself: ‘I will use my country for my own benefit’? Or are you a devoted politician, who whispers into the ear of his inner self: ‘I love to serve my country as a faithful servant’?

Later in 1965 it was referred to in another translation as ‘The New Frontier” matching President Kennedy’s theme on his 1960 acceptance speech with the following text:

“Come and tell me who and what are you. Are you a politician asking what your country can do for you or a zealous one asking what you can do for your country?”

So was it any wonder that his book ended up in the pockets of these brave soldiers? I can’t help but ask myself, what would Gibran have said about it? As a champion and campaigner for peace and unity – What would he have thought of his Prophet of War? I do have to end this piece with a …”To be continued” as I feel it is not the end of this story. In recent developments, I have acquired a copy of the book with soldiers names imprinted on the inside cover. My search continues.

Glen Kalem

Sydney, Australia

<