-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

by Francesco Medici

Copyright © Franceso Medici all rights reserved 2019

Translations from the Original Spanish into English by Hilda de Windt-Ayoubi

A few months before dying, Kahlil Gibran received in his New York studio two lady admirers. One of the women was an old acquaintance of his, Idella Purnell Stone (1901-1982), a Mexican-born poet, journalist and author of children’s tales (her best-known work is Bambi, a rewrite of Felix Salten’s original version, “Bambi, A Life in the Woods,” on which the famous 1942 Walt Disney’s film is based).1 She was also the editor of ‘Palms,’ a poetry magazine that was published from 1922 to 1930 and that featured Gibran himself.

acquaintance of his, Idella Purnell Stone (1901-1982), a Mexican-born poet, journalist and author of children’s tales (her best-known work is Bambi, a rewrite of Felix Salten’s original version, “Bambi, A Life in the Woods,” on which the famous 1942 Walt Disney’s film is based).1 She was also the editor of ‘Palms,’ a poetry magazine that was published from 1922 to 1930 and that featured Gibran himself.

Purnell’s comrade did not speak English and was very humble with Gibran. She nourished an “eager, child-like faith” to him and addressed him as “maestro” (master). Purnell, who had arranged the appointment, was there primarily to act as interpreter for her friend, who sometime before had told her that “there was one person she wished above all others to see in New York, Kahlil Gibran.”

That stranger was no less than Chilean poet, educator and feminist Gabriela Mistral (pseudonym of Lucila de María del Perpetuo Socorro Godoy Alcayaga, 1889-1957), who went on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1945. During the course of the evening, she “questioned him closely about eternal verities which she felt he understood better than she.”2 Although distraught with the man’s painful state of physical prostration, she was fascinated by his wisdom, and after his death, she wrote in a short published text in Spanish:

“He was born in the region of Mount Lebanon, and he was the common Arab with a vulgar face; but in his soul, he carried all of the East. Extreme Chinese finesse was in him; Hindustani metaphysics sparkled through his conversation; a few touches of the pure spirituality of Persia and sometimes the sting of Jewish intensity. All this, gone through some scepticism coming from Solomon, which gave one or another of his poems and his own talk, a certain nutty, bitter and comforting flavor. His fame challenged that of Tagore and, for some people who were disappointed with the ‘abusive honeys’ of the Indian, the Lebanese was superior.

The East had been as much or more aware of him as New York where he had lived for twenty years. He was pleasantly proud of the esteem from the East and showed me, with the gesture of a spoiled child, editions of his pampered poems, some manuscripts, true wonders in Arabic.

The East had been as much or more aware of him as New York where he had lived for twenty years. He was pleasantly proud of the esteem from the East and showed me, with the gesture of a spoiled child, editions of his pampered poems, some manuscripts, true wonders in Arabic.

The baroque chaos of New York mysticism had spoiled him a little bit and, particularly in his drawings, this confusion of his mind appeared in transcendental allegories of bad taste, which swung between Rodinean paganism and some naive spiritualism, like Miss Eddy’s “Christian Science.”3 He spoke of the gods who visited him in his friends, with a Swedenborgian or Blakean familiarity. But the god that was already lying in his entrails was that of the end of life, the god furtive and yellow like a Chinaman that doctors harshly call cancer.4

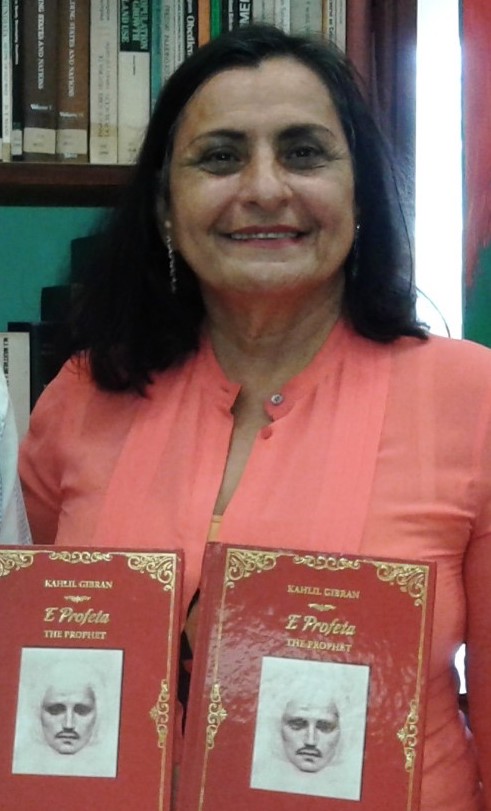

Two months after my jovial conversation with him, the wise and profound man died in a vulgar hospital, between nickel instruments and white lacquered cots.”5 But Mistral also left, after that first encounter with the poet, a 21-page long copybook handwritten in pencil completely dedicated to Kahlil ‘Gilbran’ which is currently kept safe in the archives of the National Library of Chile.6 It was kindly and entirely translated, for the first time and just for this paper, from the original Spanish into English by Hilda de Windt-Ayoubi, a fine Gibran scholar and translator of “The Prophet” into Papiamento (a Caribbean Portuguese-based Creole language):7

“Two months ago I met Kahlil Gibran, an oriental prophet, in the terrible city of New York. A man of forty-seven years old resembling forty, solitary as the Syrian, common in his face and body, being so noble in intellectual features, slow to speak, voluntarily esoteric. The cancer was already consuming his viscera and however, the pallor of the illness did not show on his face, which like an anti-sacrament gives a visible sign of the invisible illness. Now I understand that the beverage of strained fruits which he gave [Idella (Purnell Stone)] and me was part of his own diet. In midwinter, he put some unforgettable Californian plump and juicy apples and autumn pears on a beautiful fruit platter on my knees and told me some jokes about Pomona.8 During three hours I was being turned into a pulp of apples and obscure and clear concepts of Kahlil Gibran.

We talked about ‘The Madman’ and ‘The Prophet’ and he stood up, with the slowness which is the only oriental thing that is left in his New York body, to look for the numerous editions of the poems. He sets aside those in the English and European languages and gives me the Oriental ones to take a look at and enjoy: small books, written in Chinese, Persian and Syrian with vignettes both exquisite and sumptuous, loaded with colors. Then smiling, he hands me over an old issue of the Chilean student magazine ‘Juventud’ where ‘El loco’[‘The Madman’] was published about twelve years ago in the very faithful translation by Mrs. [Adela] Rodríguez de Rivadeneira.9

Then he hands me over as well the edition of ‘Repertorio Americano,’10 in which we meet the people of the South. We talk about the extensive prologue of [Roberto] Brenes Mesén.11 I leaf through the book; I give him back the two small booklets in which we learned to love him and he puts them in one of those small and organized shelves. I regret that I have to arrange them in the shelves in which there seems to be very little and from where he will lead me to many wonders during our conversation. I think that, besides being a New Yorker, he has the orderliness of a good bachelor who has to accommodate his life in a single room and so I tell him.

The study of Brenes Mesén speaks by the way, of oriental doctrines, of those mystical lightings that abound in the work of the Syrian poet and I ask him about that. I also ask him by the way about his religious ideas and how a Lebanese quasi-prophet adjusts to live happily a few steps away from the ‘Most High’ and in a terrible neighbourhood of New York.

To illustrate the baroque and obscure ideology that he is going to present to me, he goes to look for another one of those small pieces of furniture in which a whole portfolio of his drawings can fit. I did not know it: Gibran paints and paints so much, that when I asked people over here about him, some only knew the painter. The poems are clear, light and sharp: remember “The Sleep-Walkers,” for example; but the illustrations of those poems are pretty intricate, dark, and of bad taste; of a taste very in vogue, pseudo-mystical, pseudo-cabalistic that attracts the North American ingenuousness. My companion [Idella] explains to me that Gibran makes them expressly to illustrate his books, but that he usually brings them together in expositions that bring him a lot of money.

I have never liked Greco-Roman mythology very much, even if it is part of folklore because it is folklore without innocence, cultured and pedantic folklore, that is to say, an anti-folklore. Less than the Greek mythology, I still like its mixture with its neighbors from Asia and Africa, so different, and who are so offended by this mixture.

The illustrations of Gibran seem to me like that; there are naiads, sirens and other intellectual occurrences participating in allegories with creatures from other places and even from other areas; Chinese, Arab and Hindustani. Gibran places them one by one on a short stand which he puts between us, and in a kind of ritual, in front of the pictorial witness, he starts giving me one after another of his concepts of life. I really regret that I did not write down his conversation that same night; so multicolored it seemed to me that he had decided to give it for his ordination to himself and I am confusingly writing this confusing speech of his that cannot be clarified anymore.

I remember precisely – because he repeated it many times – his concept of the gods: ‘We are the gods and where we least expect there is an assembly or an agape of demigods that are equivalent to the colloquies of Apollo, Juno and Jupiter and the others.’

‘That of the kingdom of God is within you, that is very true, only in a different way as the parochial mind understands it.’

‘The great paganism, the Greek-Roman, was much more than the blend of fables that has served to make us laugh. False that it was a complete, materialistic system. You who love his Virgil, has not learned more than the common teaching people – that crowd is from the descent into hell?’.

Gibran’s conversation is merged perfectly with his paintings. But I cannot discover the Gibran of ‘The Madman,’ the wise and sarcastic man, who like Solomon, has chewed the nut of the human truth. I ask him which Gibran is the present one if that is the very pagan of the illustrations loaded with nude Greeks or the Syrian one of fifteen years ago.

‘Be patient. Let us talk a lot until you see the spokes of the wheel come together: clean yourself from the prejudice of duality. It is the damage in everything. Neither a materialist nor a drunkard of spirituality; the two, perfectly related. I have already attained the agreement; those who love me, that they attain it too.’

The three-hour conversation continued on these issues. I did not know that the man was already contemplating the other side: that he was already getting into the dense forest of cypresses from where one can no longer leave and return to the banal paths; that he had only months, four months of conversation left with us. He is already in the company of the real gods – not of the ones he himself created of a similar rank, fortifying and fooling himself – in a neighborhood of New York. But like everyone he is learning for himself and he cannot teach us anything, dropping us not a crumb to the table of hunger and craving which is ours.

Complicated and rich Kahlil Gibran, son of the East transplanted in the West for his fortune and for his misfortune.[12]

* This article is based on an excerpt from the paper Tracing Gibran’s Footsteps: Unpublished and Rare Material, in Gibran in the 21th Century: Lebanon's Message to the World, edited by H. Zoghaib and M. Rihani, Beirut: Center for Lebanese Heritage, LAU, 2018, pp. 93-145.

The author would like to thank Mrs Hilda de Windt-Ayoubi for translating Mistral’s papers into English.

1 Idella Purnell, Felix Salten, “Walt Disney’s Bambi,” Illustrated by The Walt Disney Studio, Boston: D.C. Heath and Company, 1944.

2 Purnell related the episode twenty years later in a review of the English edition of Mikhail Naimy’s biography of Gibran entitled “Gift for Mimicry Harms Poet; With Head in Clouds and Feet Mired,” in “Los Angeles Daily News,” Nov. 4, 1950, p. 9.

3 A religious movement founded by Mary Baker Eddy (1821-1910) in New England in the latter half of the 19th century.

4 An autopsy revealed in truth that the cause of death was “cirrhosis of the liver with incipient tuberculosis in one of the lungs.”

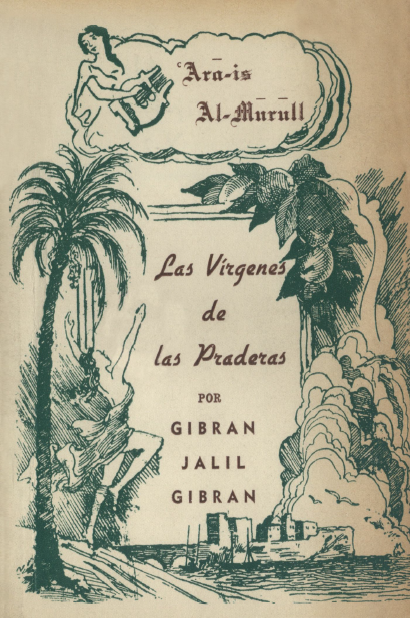

5 “Gibran Jalil Gibran por Gabriela Mistral,” in Gibran J. Gibran, “Las Virgenes de las Pradreras” [“Nymphs of the Valley”], Traducción de Haikal Obaid Raide, Santiago - Chile: Dunia, 1961, p. 9 (translated by Hilda de Windt-Ayoubi).

6 Mistral, Gabriela, 1889-1957, Cuaderno 67, manuscrito, Gabriela Mistral. Archivo del Escritor, Biblioteca Nacional Digital de Chile: http://www.bibliotecanacionaldigital.cl/bnd/623/w3-article-142835.html

7 Cf. Kahlil Gibran, “E Profeta”, Tradukshon for di ingles di Hilda de Windt-Ayoubi, Introdukshon di Suheil Bushrui, Bethesda: University Press of Maryland, 2013.

8 Pomona was the Roman goddess of fruitful abundance. She was said to be a wood nymph, famous for her devotion to her orchards and for her chastity.

9 Cf. Kahlil Gibrán, “El loco: sus parábolas y sus poemas” [“The Madman: His Parables and Poems”], in “Juventud,” no. 17, Oct. 1922, pp. 22-63.

10 “Repertorio Americano” was a cultural magazine published in San José, Costa Rica by Joaquín García Monge, on and off between 1919 and 1958, and it represented a significant forum of discussion for the Latin American intellectuals. García Monge also published the first Spanish translation of Gibran’s “The Madman” (“El loco: sus parábolas y sus poémas,” San José de Costa Rica: El Convivio - García Monge, 1920).

11Cf. Roberto Brenes Mesén, “El loco de Kahlil Gibrán,” in “Juventud,” no. 17, Oct. 1922, pp. 20-21.

12 Cf. Gabriela Mistral, “Khalil Gibrán (1931),” in “Recados para hoy y mañana. Textos inéditos,” Tomo I, Compilado y seleccionado por Luis Vargas Saavedra, Santiago de Chile: Editorial Sudamericana, 1999, pp. 36-39.