-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

Mercedes de Acosta: “Gibran Was a Great Spiritual Teacher”

edited by Francesco Medici and Glen Kalem-Habib

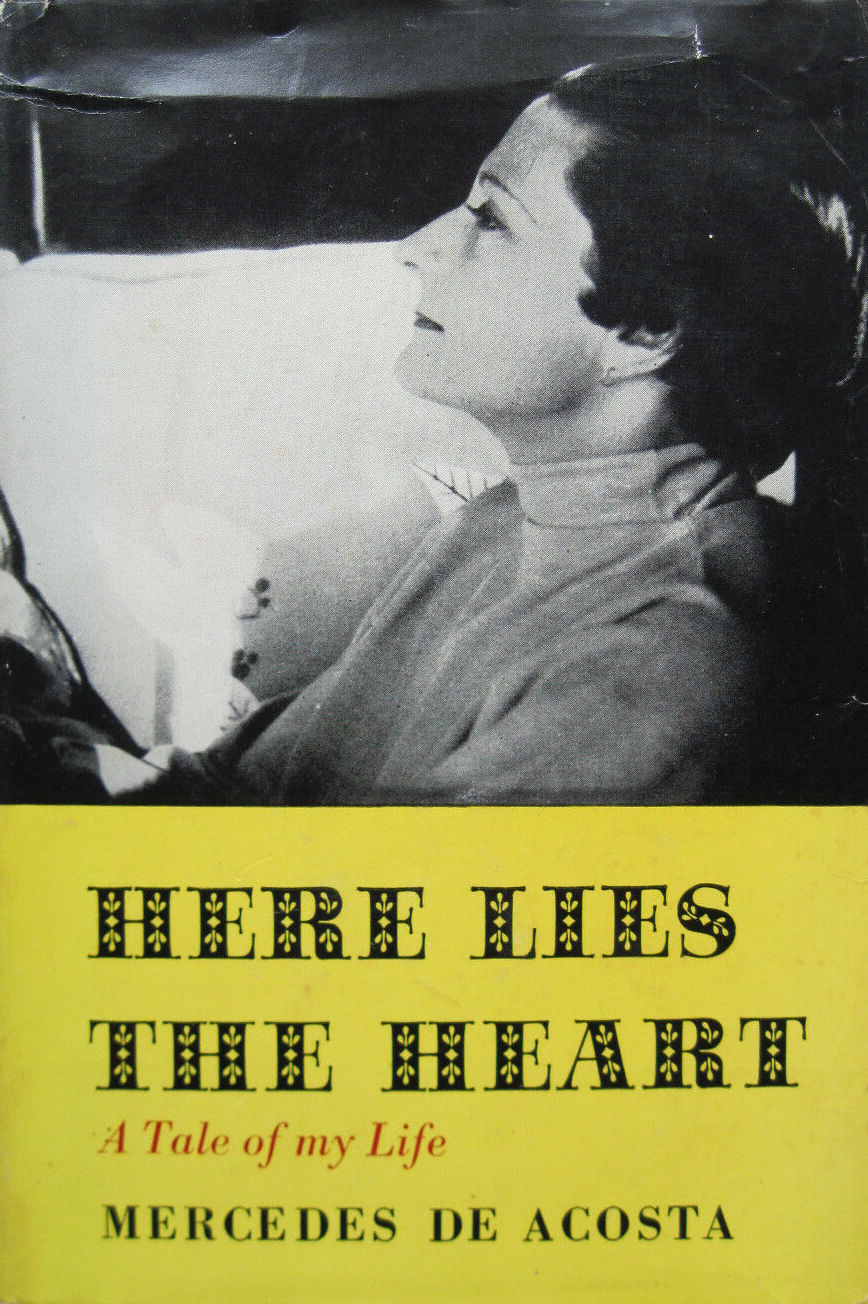

Mercedes de Acosta (1892-1968) was an American poet, playwright, and novelist. She was professionally unsuccessful but is known for her many lesbian relationships with famous Broadway and Hollywood personalities and numerous friendships with prominent artists of the period.  In 1960, when de Acosta was seriously ill with a brain tumor and in need of money, she published "Here Lies the Heart: A Tale of My Life". Her memoir contains the following pages on Kahlil Gibran.

In 1960, when de Acosta was seriously ill with a brain tumor and in need of money, she published "Here Lies the Heart: A Tale of My Life". Her memoir contains the following pages on Kahlil Gibran.

Jack Barrymore[1] and I were friends. Through the years in which I knew him and until he died, our friendship was of such a character that, in the ordinary sense, it might have been termed unrealistic. With the exception of Michael Strange[2], Kahlil Gibran, and Ned Sheldon[3], I never saw Jack with other people.

I never went to a play or a party with him and I never went anywhere with him in public. Yet I think I can say that on a certain level – in fact on a number of levels – I knew him intimately. Often over the years, whenever he was unhappy or in trouble, he used to call me on the telephone, generally late at night, and talk about his personal problems for hours. It was a one-sided friendship because Jack, being a supreme egotist, hardly ever asked me anything about myself. I didn’t resent it. From the beginning, it seemed quite natural that it was he who turned to me for advice and comfort. I hardly remember ever calling him or making any effort to see him. Sometimes there were long stretches – even years – when I didn’t hear from him at all, but I always knew that sooner or later he would turn up again in my life.

I never went to a play or a party with him and I never went anywhere with him in public. Yet I think I can say that on a certain level – in fact on a number of levels – I knew him intimately. Often over the years, whenever he was unhappy or in trouble, he used to call me on the telephone, generally late at night, and talk about his personal problems for hours. It was a one-sided friendship because Jack, being a supreme egotist, hardly ever asked me anything about myself. I didn’t resent it. From the beginning, it seemed quite natural that it was he who turned to me for advice and comfort. I hardly remember ever calling him or making any effort to see him. Sometimes there were long stretches – even years – when I didn’t hear from him at all, but I always knew that sooner or later he would turn up again in my life.

At this particular time [1917] he called me one night very late. He said he had been asked by a publisher to pose for a black and white drawing to be done by an artist called Kahlil Gibran. Jack said, “The fellow is Persian or Syrian – some such country – and he wants to include me in a book of drawings. I have to pose tomorrow morning and I wish you would come with me. I’m frightened out of my wits to go alone.” So he called for me the next morning and together we went down to Kahlil Gibran’s studio on West Tenth Street. I am ashamed to say that at this time I was as ignorant about Gibran as Jack was, which is enough to have crossed us both off as a pair of idiots.

in a book of drawings. I have to pose tomorrow morning and I wish you would come with me. I’m frightened out of my wits to go alone.” So he called for me the next morning and together we went down to Kahlil Gibran’s studio on West Tenth Street. I am ashamed to say that at this time I was as ignorant about Gibran as Jack was, which is enough to have crossed us both off as a pair of idiots.

Kahlil Gibran received Jack and me quietly and graciously in his studio. I apologized for having come uninvited, but he put me at ease at once and made me feel it was the most natural thing in the world that I should be there. To prove this he expressed a wish to do a drawing of me, too. I was deeply impressed by his looks and by his personality.

In stature, he was a small man, but as his head was massive and remarkably shaped, he looked taller than he actually was. I never saw a nobler brow than his. The most impressive thing about him was his eyes. He seemed to look at you with a gaze that came from some deeper region than the physical. When later I came to understand certain things better I felt that – like Buddha – he must have had a third eye. He was a poet, artist, musician, philosopher, mystic, and beyond all these – a great spiritual teacher. He was an initiate who came at a certain moment to bring a spiritual message to the Western world, as the thousands of pilgrims who yearly visit his grave in the Monastery of Mar Sarkis in Bsherri demonstrate. Anyone who wishes to know him can read his numerous books, among them The Madman, The Forerunner, and The Prophet.

This particular morning, when he began to work, he had not drawn ten lines before Jack and I knew he was a master artist. Jack himself could draw well and was a gifted artist. I saw him relax as Gibran continued the portrait, and at the end, after several hours, a strong and fine head of Jack was on the paper. During these hours Gibran had only spoken once or twice, yet his silence seemed light and not at all awkward. Jack said afterward, “Actors could learn the voice of silence from this man.”

As we left the studio, almost as though it was an afterthought, Kahlil Gibran handed me a book. He said, “Read this... and when you have finished it call me and tell me what you think of it.”

That night in bed I opened the book. On the title page, I read The Bhagavad Gita[4]. I had only vaguely heard of it – an admission that I am now ashamed to make. That same night I started to read it, and when I had finished the last page full daylight was streaming into my room. I do not pretend that I fully understood all that I read, but I drank in the words somewhat like a parched camel who suddenly comes upon a spring at which he can quench his thirst. When I closed the book, instead of feeling exhausted after so many hours reading I felt revitalized and exalted. I knew that this book contained knowledge that could sustain me all my life.

As soon as I felt I could call Kahlil Gibran without waking him up, I rang his number. It was he who answered and heard the excitement in my voice, although I tried to sound calm. I asked him if I could come at once to see him. When he said I could, I rushed from the house barely dressed and without breakfast. As he opened the door and I burst into his studio I said, “Why has no one ever told me about this book before? It has already revolutionized my life!”

Quietly and gently he sat me down. He said that he had hoped I would have just this reaction. He added that had I not reacted favorably, he would not have seen me again. We sat together for several hours while he explained passages from the Gita and answered my questions. These hours seemed timeless. He also told me about the great Hindu epic poem “The Mahabharata,”[5] a kind of moral encyclopedic teaching in accordance with the Vedas[6]. I remember he told me that Christianity – as taught by the churches – would have to be re-stated. He said that Christianity, in the accepted sense, had failed – but that Christ had not, and never would.

When I left his studio that day he gave me another appointment and promised me further instruction. He gave me the Upanishads to take home with me and laughingly said, “If you devour this book the way you did the Gita, you will surely have spiritual indigestion.”

When I reached home, for the first time in my life I had a sense of inner peace, a thing I had never achieved in a church.

* Mercedes de Acosta, Here Lies the Heart: A Tale of My Life, New York: Reynal, 1960, pp. 91-93.

[1] John Sidney Blyth Barrymore (1882-1942) was a famous American actor on stage, screen and radio. He was known by family, friends and colleagues as ‘Jack.’

[2] Blanche Marie Louise Oelrichs (1890-1950) was an American poet, playwright and theatre actress. She first used the masculine nom de plume Michael Strange to publish her poetry in order to distance her society reputation from its sometimes erotic content, but it soon became the name under which she presented herself for the remainder of her life. She was Jack Barrymore’s second wife, from 1920 to 1925.

[3] Edward Brewster ‘Ned’ Sheldon (1886-1946) was an American dramatist.

[4] The Bhagavad Gita (“The Song of God”), often referred to as the Gita, is a 700-verse Sanskrit scripture that is part of the Hindu epic Mahabharata.

[5] The Mahabharata is one of the major Sanskrit epics of ancient India.

[6] The Vedas are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. They constitute the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature and the oldest scriptures of Hinduism.