-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

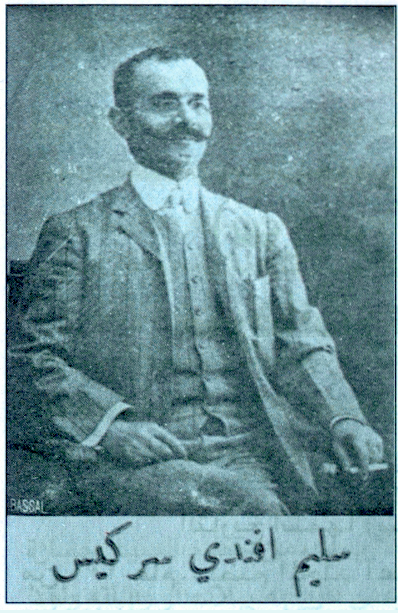

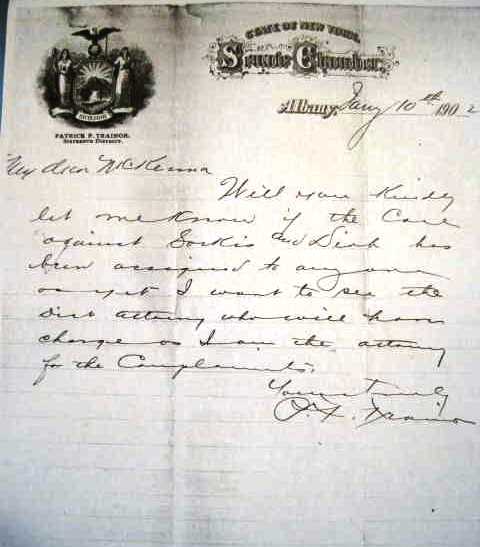

made him few friends among segments of the Syrian immigrant colony, most of whom took their Christian religion very seriously. Sarkis seems to have taken politics seriously, albeit often dashed with humor, but not religious dogma, and not respect for those in powerful political positions. He never seemed to attract the same strong following and reputation he had held in Egypt as a political agitator and leader, probably as a result of the enemies he made among Colony members. However, he had at least a few early-Syrian Colony friends, including Najeeb Diab, editor of Meraat ul Gharb (“Mirror of the West”), and Kahlil Gibran’s publisher, who stood-by Sarkis after he was attacked at 81 Washington St in 1901.

made him few friends among segments of the Syrian immigrant colony, most of whom took their Christian religion very seriously. Sarkis seems to have taken politics seriously, albeit often dashed with humor, but not religious dogma, and not respect for those in powerful political positions. He never seemed to attract the same strong following and reputation he had held in Egypt as a political agitator and leader, probably as a result of the enemies he made among Colony members. However, he had at least a few early-Syrian Colony friends, including Najeeb Diab, editor of Meraat ul Gharb (“Mirror of the West”), and Kahlil Gibran’s publisher, who stood-by Sarkis after he was attacked at 81 Washington St in 1901.

You may have heard that Gibran has been writing for the last three years some articles to al-Mohajer of NY, articles under the heading of “Tears and Smiles”. They are very fine. I read every one of them. I copy some to my magazine. I want to tell you a secret feeling of my own. I may be wrong but let me say it. He only began these articles and this style since I introduced him to you. I see you in every line of those articles. I feel that either you are helping him or he has given us your impressions of life.

In the same letter, Sarkis congratulates himself for introducing Barry to Gibran, writing that he “gave [her] Gibran”:

...As for Rustum, I only asked him to call and see you that he may write to me about you. I know that he is not the man you like, but he was my messenger only. When I wanted to give you a sample of the Syrian I gave you Gibran and I do not regret it. Do you?[4]

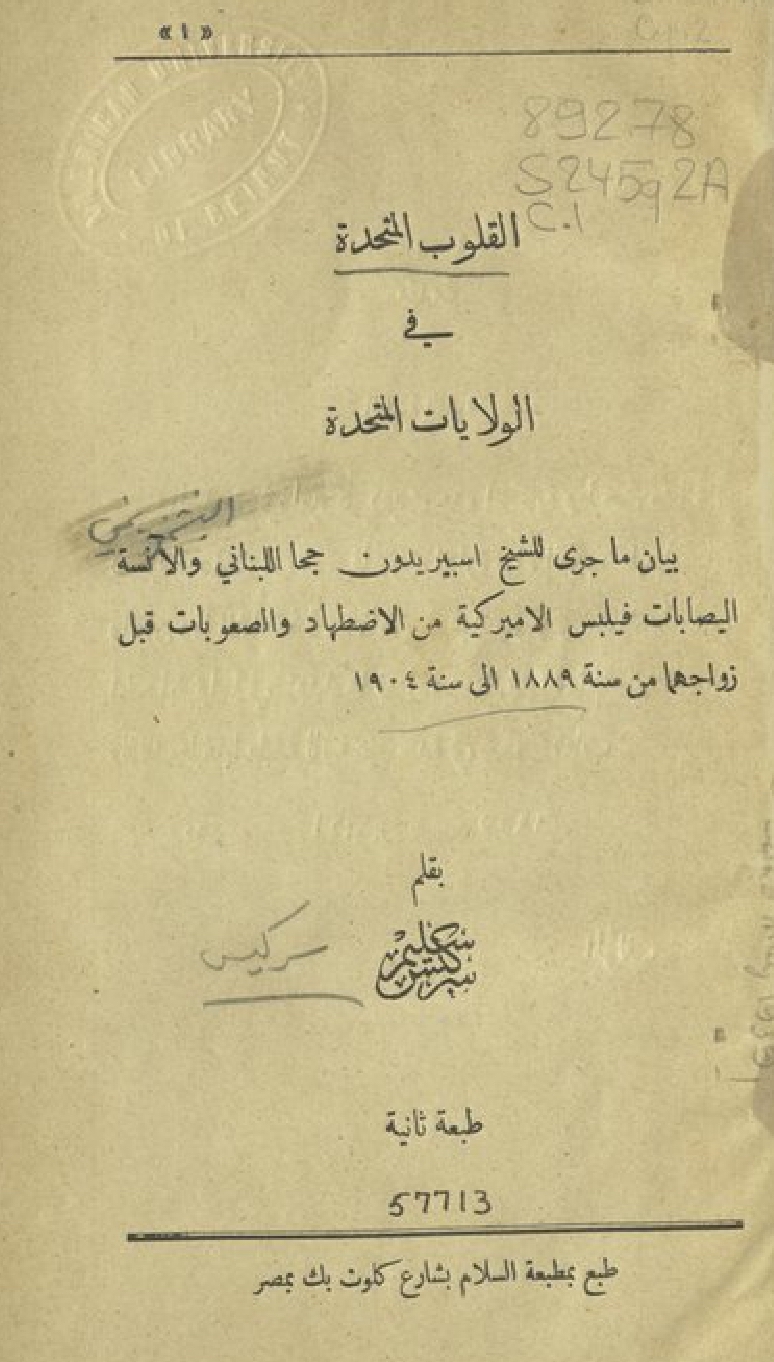

Sarkis did not live-up to the moniker of “The Syrian Lafayette”, perhaps because of the enemies he made in the Colony, or perhaps because of a lack of financial success; he closed Al Musheer in 1903, and returned to Cairo in 1905 after setting-up two short-lived newspapers in Massachusetts. In the interim period he became an editor at Meraat ul Gharb, and in 1904 its Press published al-Qulub al-Muttahidah fi’l-Wilayat al-Muttahidah (“United Hearts in the United States”), that is considered the first Arabic novel written outside of the Middle East.

He had left a bride in Cairo, and liberalism was increasing in both the Ottoman Empire and in Egypt. Now back in Cairo, he started a new journal, Majallat Sarkis (Sarkis Magazine), which he published until his death in 1926. There he continued using humor to be a thorn in the side of government and religious officialdom, while joining a new circle of friends in the salon of May Ziadeh each week.

He had left a bride in Cairo, and liberalism was increasing in both the Ottoman Empire and in Egypt. Now back in Cairo, he started a new journal, Majallat Sarkis (Sarkis Magazine), which he published until his death in 1926. There he continued using humor to be a thorn in the side of government and religious officialdom, while joining a new circle of friends in the salon of May Ziadeh each week.  Following the First World War, he was an advocate of a “Greater Syria” including modern-day Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Palestine, and Israel, and was Secretary of the United Syrian Club, which included prominent Moslems and Christians (such as the Islamic reformer Rashid Rida) but failed in its efforts to avoid splitting the region into separate states.He made the US papers at least twice after his return to Cairo; first in 1916 when he cabled Meraat ul Gharb “Famine in Lebanon. 80,000 dead”, which appears to be the first notice of the 1916 Mt. Lebanon famine in the United States, and was printed in newspapers throughout America. His second well-reported news item was in 1919 and was more in keeping with the earlier indications of his sense of humor: he applied for the job of “Kaiser Custodian”, for compensation, based on his 1898 condemnation of the Kaiser as a “madman” (and assumedly for the mustache critique), for which he had been punished.[5]His zeal seems to have had a limited audience in the early New York Syrian Colony, but during his second Cairo period he appears to have found a wide number of readers who enjoyed his wit and style. While no “Syrian Lafayette”, Sarkis was an important advocate of free expression in the Arab World, leaving a body of work including ten books, editorial work on five newspapers, including Al Ahram, several important enemies, and a few strong friendships; not to mention his matchmaking work for Kahlil Gibran.

Following the First World War, he was an advocate of a “Greater Syria” including modern-day Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Palestine, and Israel, and was Secretary of the United Syrian Club, which included prominent Moslems and Christians (such as the Islamic reformer Rashid Rida) but failed in its efforts to avoid splitting the region into separate states.He made the US papers at least twice after his return to Cairo; first in 1916 when he cabled Meraat ul Gharb “Famine in Lebanon. 80,000 dead”, which appears to be the first notice of the 1916 Mt. Lebanon famine in the United States, and was printed in newspapers throughout America. His second well-reported news item was in 1919 and was more in keeping with the earlier indications of his sense of humor: he applied for the job of “Kaiser Custodian”, for compensation, based on his 1898 condemnation of the Kaiser as a “madman” (and assumedly for the mustache critique), for which he had been punished.[5]His zeal seems to have had a limited audience in the early New York Syrian Colony, but during his second Cairo period he appears to have found a wide number of readers who enjoyed his wit and style. While no “Syrian Lafayette”, Sarkis was an important advocate of free expression in the Arab World, leaving a body of work including ten books, editorial work on five newspapers, including Al Ahram, several important enemies, and a few strong friendships; not to mention his matchmaking work for Kahlil Gibran.