-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

by Philippe Maryssael, retired translator and terminologist.

Arlon, Belgium, October 13, 2020.

Barbara Young (1878‑1961), the pen name of Henrietta Boughton, née Breckenridge, was a literary critic with the New York Times in the early 20th century. She became Kahlil Gibran’s personal secretary in 1925 and it was she who carried the agonizing Gibran to the Saint Vincent Hospital in New York on April 9, 1931. The next day, April 10, 1931, Gibran passed away, diagnosed having liver cirrhosis and tuberculosis.

Barbara Young is best known for her book This Man from Lebanon: A Study of Kahlil Gibran, which was published by Alfred Abraham Knopf in 1945.

On January 8, 1932, Kahlil Gibran’s first posthumous book, The Wanderer, His Parables and Sayings, was published by Alfred Knopf. During the last days of his life, Gibran was finalizing the manuscript that Barbara Young eventually brought to his publisher.

Barbara Young was also a poetess in her own right. In addition to a couple of books of poems, she published a short story that was privately printed, presumably in February 1932, titled The Man Who Could Not Die: A Story of Judas The Disciple.

Cover of The Man Who Could Not Die

That short story is an echo to Kahlil Gibran’s 318th aphorism from Sand and Foam, a Book of Aphorisms (1926):Was the love of Judas’ mother for her son less than the love of Mary for Jesus?

Before the story begins, Barbara Young wrote the following note as an introduction:

Note: This story of Judas makes no pretense to authenticity. In it, the theory of this disciple’s suicide is rejected, and he is assumed to have lived out an interminable and tragic existence, half-mad from the day of the crucifixion of his Lord, and entirely mad at the end.

The theme of madness echoes Kahlil Gibran’s short texts from his first book in English, The Madman, His Parables and Poems (1918). The Madman is also the title of a poem from The Wanderer, and a key character in two of his long-lost theatre plays Lazarus and His Beloved and The Blind, which were eventually found by his namesake cousin, the sculptor and painter Kahlil George Gibran (1922-2008), in a box of documents he inherited from Kahlil Gibran’s sister Marianna. Those two plays were published in the seventies and eighties.

Aphorism no. 180 from Sand and Foam also refers to madness, at least alleged madness:

They deem me mad because I will not sell my days for gold;

And I deem them mad because they think my days have a price.

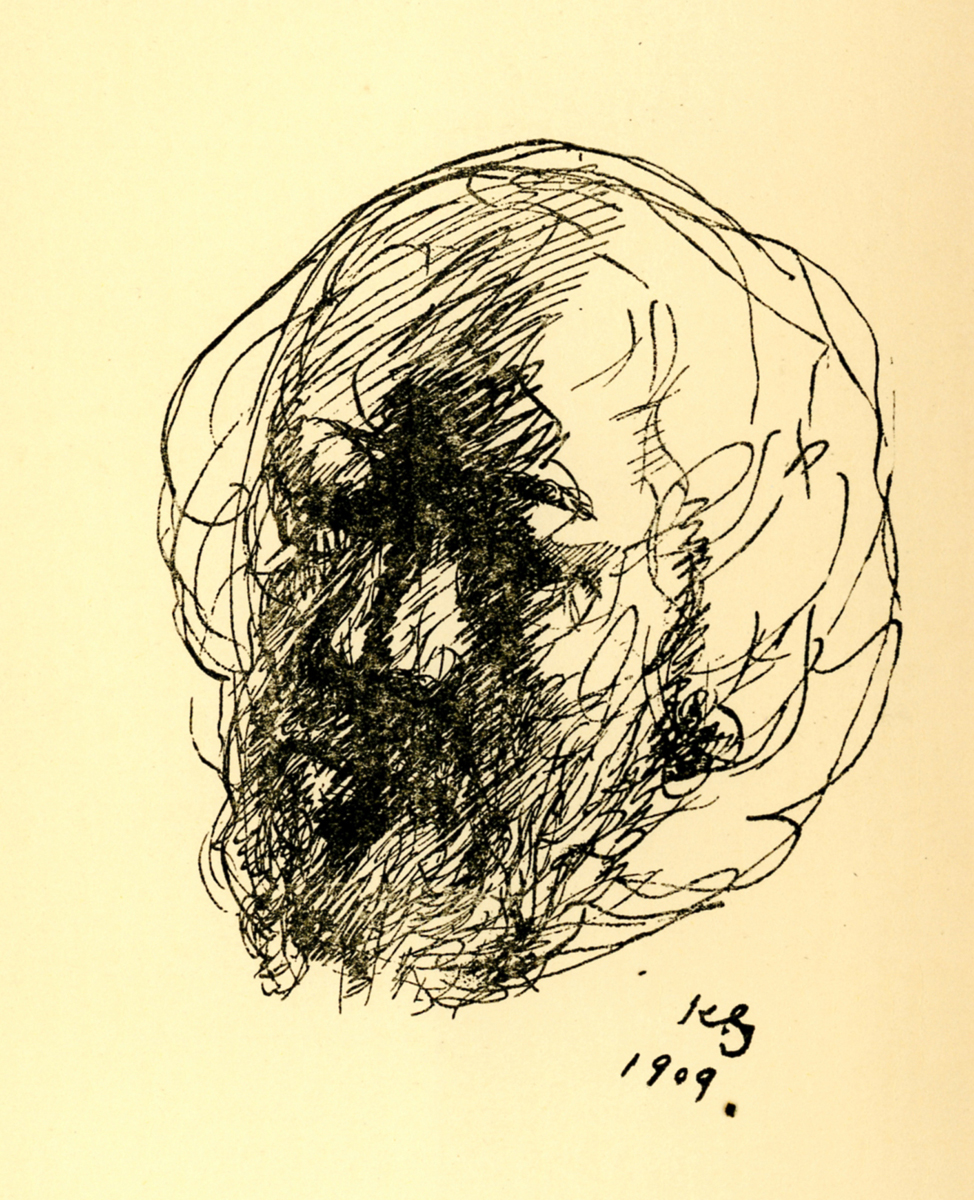

The unexpected story of The Man Who Could Not Die is that of Judas Iscariot who would not have committed suicide after he betrayed his Lord and Master on the Mount of Olives and had to live a miserable and tortured life between half-madness and complete madness when death eventually caught up with him and set him free. It is illustrated by one of Kahlil Gibran’s own drawings from 1909. Had it not been used to illustrate the book, it would have remained unknown to the general public as it most probably was amongst Gibran’s works that Barbara Young personally owned.

Drawing by Kahlil Gibran

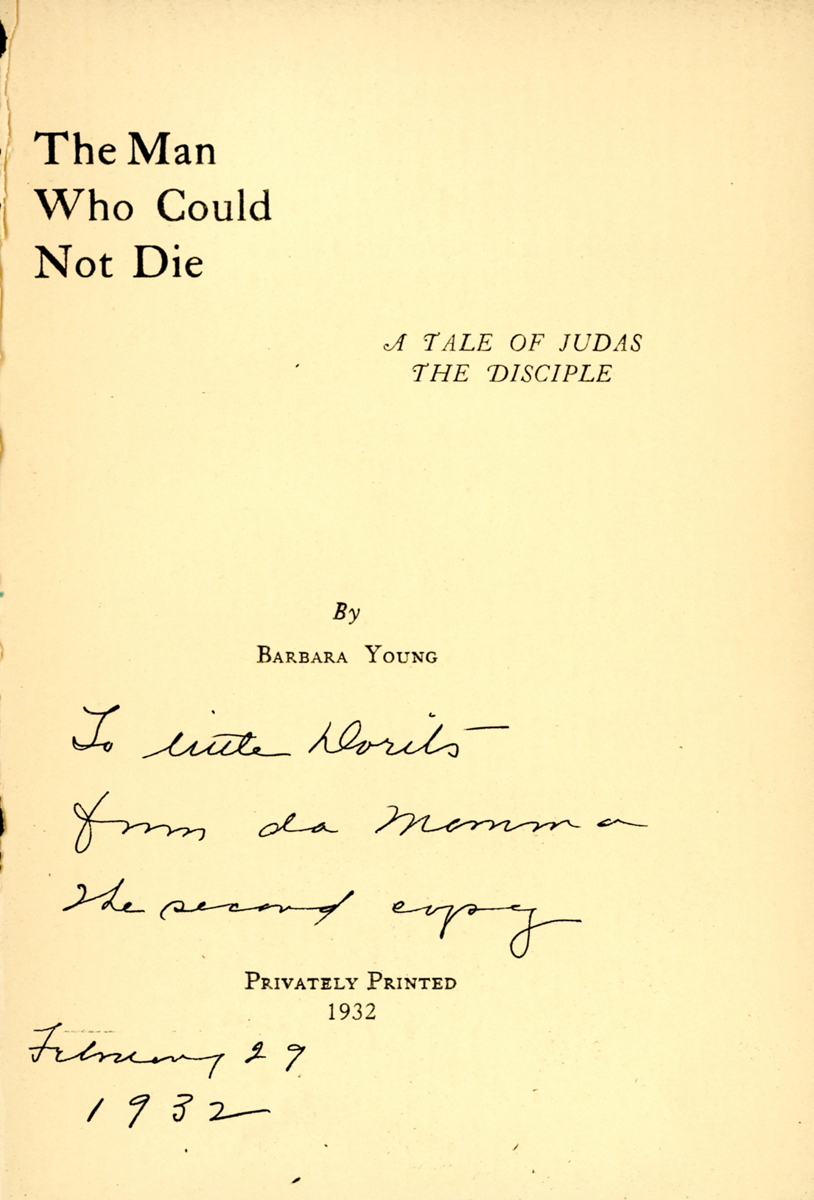

The title page bears a short inscription dated February 29, 1932.

Title page with inscription

Courtesy of the Kahlil Gibran Collective, the book is made available to you in its entirety in the KGC archive.

Barbara Young's signature

Philippe Maryssael was born in Brussels, Belgium, in 1962. He studied translation in Brussels in the early 1980s. He later studied terminology and terminotics, the set of techniques involving the use of computer software in conducting terminology research on vast text corpora and deploying terminology database and translation memory solutions in support of the translation business.

His first job was as a bank clerk in Brussels. After a couple of years, he became a professional translator and terminology pioneer in the insurance and financial sectors before he moved to Luxembourg and joined a European financial institution as a translator-reviser, terminologist, and computer-aided translation and terminology tools specialist. There, after a decade, he changed the course of his career and became a business process manager involved in paving the way to the institution-wide dissemination of business process optimisation and re-engineering practices.

In July 2017, he decided to retire. The time was right for him to indulge in his life-long interest in the writings of Kahlil Gibran. He started collecting first editions of the books that Gibran wrote in English. He also started comparing the numerous French translations of his works. The natural next step was his intention to provide personal translations of Gibran’s English books into French and to have them published. His first published work came out at the end of 2018: The Fol, a bilingual presentation of the text of The Madman and his new translation, with an in-depth analysis of Gibran’s use of the English language and a study of several themes across his entire body of books.

More information on Philippe Maryssael and his translation projects can be found on his personal website at http://www.maryssael.eu/en/.