-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

International Kahlil Gibran scholar and resident contributor to the Kahlil Gibran Collective Mr. Francesco Medici has unearthed a rare interview made of the poet-artist. Published in a small Alabama newspaper, The Birmingham News under the title: Kahlil Gibran, Syrian Poet-Artist, Tells How, Why He Wrote ‘The Prophet’ – The interview sheds an intimate light amoungst other things, into Gibran’s inner world, his thoughts and feelings about writing "The Prophet’ and 'Jesus Son of Man'. The reporter, Gladys Baker 1900-1957 (born in Jacksonville, FL) was a syndicated columnist-novelist and became a feature writer for the Birmingham News during the 1930's where she wrote a weekly page of copy, until retiring from newspaper work in 1942. How this small-town reporter from the deep south came to interview Gibran in NYC is a wonder, but her treasure of an interview, which was conducted in Gibran’s Greenwich village apartment, describes the ambiance of his studio, the inner workings that adorned his walls, and even his infamous bookcase. Here below is a transcription of the published interview:

Kahlil Gibran, Syrian Poet-Artist, Tells How, Why He Wrote ‘The Prophet’

***

Eastern Author Is Only One On Record Who Never Sought One Of His Own Book, Gladys Baker Finds

By Gladys Baker

Edited by Francesco Medici and Glen Kalem Habib

all rights reserved © copyright 2021

“Life is beauty: therefore live it beautifully.”

Thus spoke Kahlil Gibran, Syrian poet and artist, in an effort to sum up the philosophy which has guided his own destiny and made it possible for him to write a book which has been translated into 21 languages and read by millions of truth-seekers whose joined hands would circle the globe. The book is “The Prophet,” a slender, forceful volume which not a few critics consider the outstanding contribution of this age to the realm of practical metaphysics.

I climbed four flights of steps in a red brick building in Greenwich Village to reach the studio of Kahlil Gibran. It was a raw day at the beginning of December. Through the windows on each landing I could see that the snow had begun to fall steadily in tiny flakes, which beat against the panes like raindrops. But it was a warm oriental voice which greeted me as I entered a large room where the rich love for beauty and color was reflected. One wall was hung in altar cloths and antique vestments, worn by some Catholic cardinal; another was entirely covered by an Egyptian rug of the early twelfth century. Against the walls were hand-carved Italian chests and bookcases lined with the literary masterpieces of every nation. Here and there, scattered about the room, were choice pieces of brass which sent dancing lights to far and shadowy corners. One felt that the room was peopled by living, vibrant personalities. This was due to the portraits of famous people which looked down upon you and the creamy tones of Gibran’s nude figures which attain spiritual loveliness by reason of their occult significance.

I ran through several books of a mighty pile heaped upon a broad-surfaces table. They were autographed editions of friends, and here were names of authors who are household words in more than one country. In an inconspicuous corner were the worlds of Gibran, most of which are printed in his native language. I daresay this Eastern poet is the only author on record who never sought one of his own books, having ever had the good fortune of being presented with beautiful first editions by his host of literary admirers.

Although Kahlil Gibran, during the 12 years he has lived in America, has written many books, only a few have been printed in English. These have been “The Madman,” “The Forerunner,” “The Prophet” and “Sand and Foam.” Of these “The Prophet” is undoubtedly his masterpiece. It is the opinion of many that the book was written entirely through inspiration. I asked the author about this, and he sat in silence for a full moment before he gave me an answer.

“I do not think it was written the way most people think,”

he finally declared."When the average person speaks of any literary work being inspired he seems to mean that the words were dictated form a higher source or some such super-human procedure. Of course,” he went on, “I believe all creative work is more or less inspirational, but I wrote ‘The Prophet’ just as I write my other books. It required about 30 minutes to do each of its chapters.”

This was almost unbelievable. Those deep and vivifying passages on love and pain, religion or marriage might well be the crowning achievement of a lifetime effort.

“I wanted to write ‘The Prophet’,” Mr. Gibran continued, “ever since I was a lad of 18, when I began writing it in the Arabic language. However, my mother discouraged it, imploring me to wait until I had become older. This I did, and the next time I set my hand to do it I was studying art in Paris. But the atmosphere seemed not just right for it, so again I put it aside and it was not until I reached America that I began work on it in earnest, this time seeing the whole thing in English.” He walked across the room, picked up a copy of the volume we were discussing and stood looking at it steadily – almost impersonally. “I think I’ve never been without ‘The Prophet,’ though, since I first conceived the book back in Mount Lebanon. It seems to have been a part of me,” he concluded.

How The Public Received It

“Did you rewrite and polish it?” I wanted to know, recalling how each word gleamed like a jewel in a precious necklace. “No,” he shook his head with its patches of gray at the temples, “but I kept it for four years before I delivered it over to my publishers because I wanted to be sure, I wanted to be very sure that every word of it was the very best I had to offer.”

Then I told the poet from the East in what esteem his book was held among a few of my acquaintances. I spoke to him of a man who is noted for his brilliant mental attainments and his unselfish work for others, who uses “The Prophet” to bring back his strength and ambition and love of life when his spiritual coffers are empty; how another had declared to me the “The Bible” and “The Prophet” were the only books she really needed if all the rest of her library were swept away from her; how another friend kept it always beside her on a bedside table, reading a fragment just before retiring; and how still another finds relation by tramping off into the woods with the small black volume and absorbing its lyrical pages upon a bed of pine-needles; and what was even more typical of the book’s appeal was the story I told him of a young debutante stopping me in the lobby of a New York hotel, while I was hurrying to catch a boat for Europe, to read me parts of “The Prophet” which she had just discovered that morning at a nearby bookdealers.

“And so you see,” I concluded, “it appeals to young and old. There’s a sort of universal agelessness about the book which furnishes inspiration to everyone who reads it.”

The author of the volume we were discussing turned his head aside but not before I had noticed that his piercing brown eyes were misty. “It touches me so, when they feel like that about my little book,” he explained his emotion. “Letters have come from all parts of the world saying things like that,” he continued, and the

humility of the man was beyond question. The modesty of the truly great has been dwelt upon so often that it has become a truism; nevertheless this same humbleness of spirit is the learned Easterner’s chief characteristic. He dislikes compliments and at a word of praise will shake his head and put out his hand as if he would stop you forcibly.

humility of the man was beyond question. The modesty of the truly great has been dwelt upon so often that it has become a truism; nevertheless this same humbleness of spirit is the learned Easterner’s chief characteristic. He dislikes compliments and at a word of praise will shake his head and put out his hand as if he would stop you forcibly.

Perhaps he looks upon his work impersonally or else it is so sacred and born of such intimate communion with the Unseen that he is self-conscious about it. He would much prefer telling you about his good friend Krishnamurti or the great Debussy or some of the other portraits. Or perhaps just sit and talk of great spiritual truths which open your eyes a little wider to glimpses of the Infinite.

Kahlil Gibran is not only an oriental poet whose words sink into one’s consciousness like the whisper of muted violins, but he has brought this same quality into his drawings. The work of his hands has been exhibited in the most prominent art galleries of Europe and the original drawings which were used for illustrating “The Prophet” have been eagerly sought by several art organizations in this country with the view of placing them among their permanent collections, among these being the Metropolitan Art Museum. His drawings are done with an ordinary pencil, of which there are a number scattered about on bookcases and tables. No trick modernism has brought this wide recognition of his work. Rather is it that same ethereal quality which pervades all of his creative activities; that illusiveness which made it impossible to reproduce his original drawing of “The Prophet.”

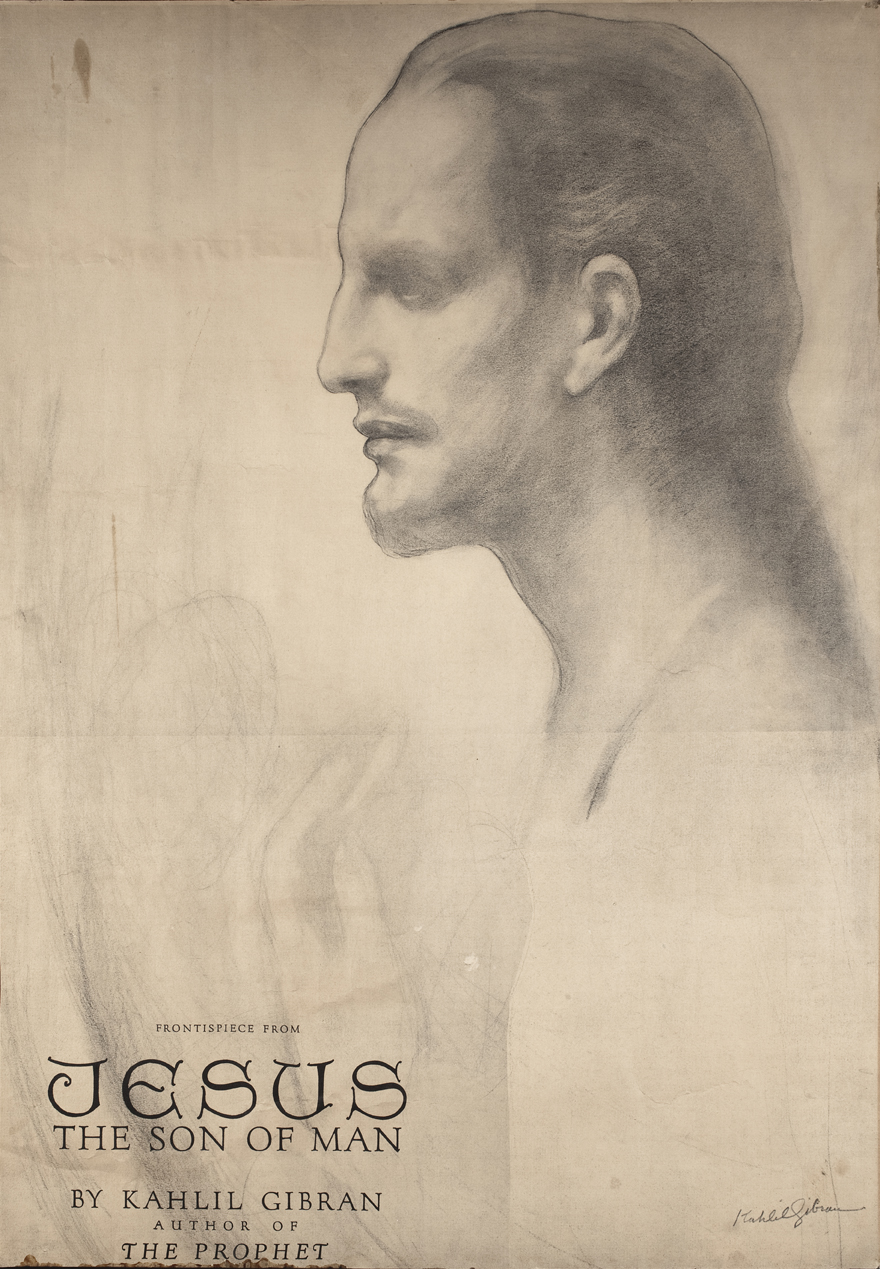

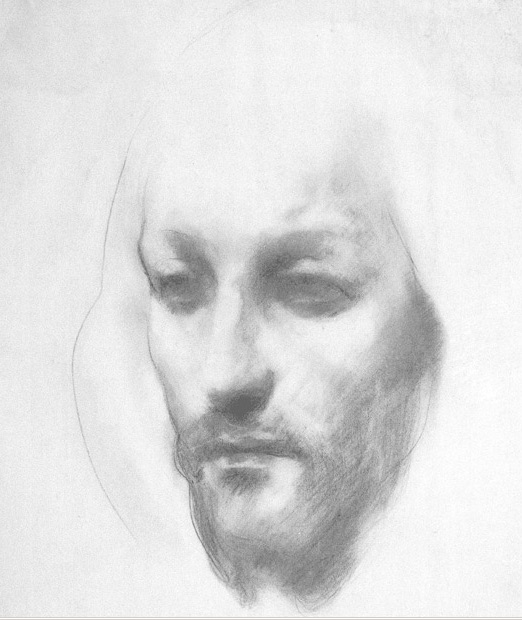

Kahlil Gibran is now working on a book which will be brought out by Knopf in the Autumn. It will be called “The Son of Man” and is the life of Jesus. It will be handled in the same style as “The Prophet.” Lyrical prose I think one would call it. In the book the writer tells the life of the Master in the words of 100 different persons who knew him. He read me parts of the original manuscript and it is the most enkindling tale to which I have ever listened. It seemed to me that this poet of Lebanon is peculiarly fitted to add his version of the life of Jesus to that long list of volumes which has accumulated through the ages, for he is imbued with the very spirit of the country in which the Nazarene wandered and taught the gospel. “The place in which I was born,” he told me, “is about as far from Nazareth as New York is from Hartford.” Thus he has geographical kinship and knows well the legends and traditions of this great historical section. He has made personal research into the lives of the people of the country made immortal by the presence of the Master.

In this new version of the life of Christ the author will not attempt in any sense a new translation, nor quibble with former writers. Rather will his volume be a series of word pictures drawn in swift, pungent sentences, but, withal, clothed in mystical garments of beauty. The illustrations for this new work are blinding with spiritual radiance. Two portraits of the Master are so exquisitely beautiful that one is brought to a state of worship before them. A rare combination of richness and simplicity runs through the work of Kahlil Gibran, whose genius burns like a candle. One finds the silver and gold of the Renaissance combined with the simple tenderness of the peasants, who toil in the fields and vineyards of Lebanon, pervading his creations. Reeling before the beauty of his expression, one is strangely humbled by the finality and truth of his simple statements.

In this new version of the life of Christ the author will not attempt in any sense a new translation, nor quibble with former writers. Rather will his volume be a series of word pictures drawn in swift, pungent sentences, but, withal, clothed in mystical garments of beauty. The illustrations for this new work are blinding with spiritual radiance. Two portraits of the Master are so exquisitely beautiful that one is brought to a state of worship before them. A rare combination of richness and simplicity runs through the work of Kahlil Gibran, whose genius burns like a candle. One finds the silver and gold of the Renaissance combined with the simple tenderness of the peasants, who toil in the fields and vineyards of Lebanon, pervading his creations. Reeling before the beauty of his expression, one is strangely humbled by the finality and truth of his simple statements.