An Excerpt from His Autobiography Introduced and Annotated by Francesco Medici

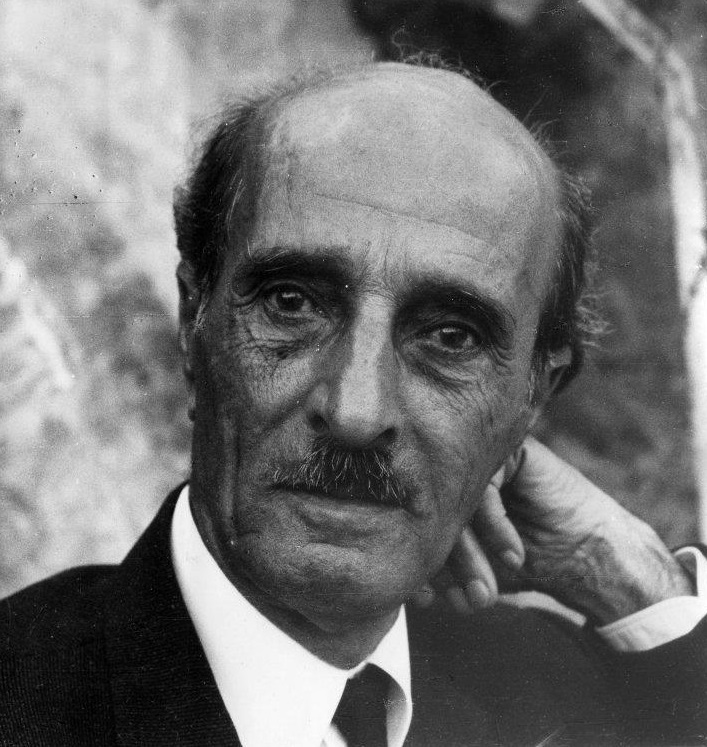

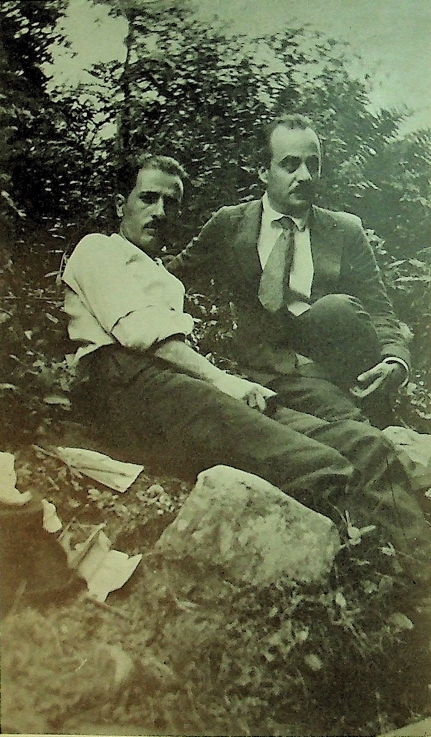

In 1934, Lebanese poet, novelist, philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Naimy (1889-1988), official member and secretary of al-Rabitah al-Qalamiyya (The Pen Bond, New York 1920-1931), published in Beirut the first biography of Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931), his associate and friend for sixteen years in the United States (he had already dedicated several pages to Gibran’s literature in al-Ghirbal [The Sieve, Cairo, 1923], a collection of critical essays which had appeared between 1913 and 1922).

In 1934, Lebanese poet, novelist, philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Naimy (1889-1988), official member and secretary of al-Rabitah al-Qalamiyya (The Pen Bond, New York 1920-1931), published in Beirut the first biography of Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931), his associate and friend for sixteen years in the United States (he had already dedicated several pages to Gibran’s literature in al-Ghirbal [The Sieve, Cairo, 1923], a collection of critical essays which had appeared between 1913 and 1922).

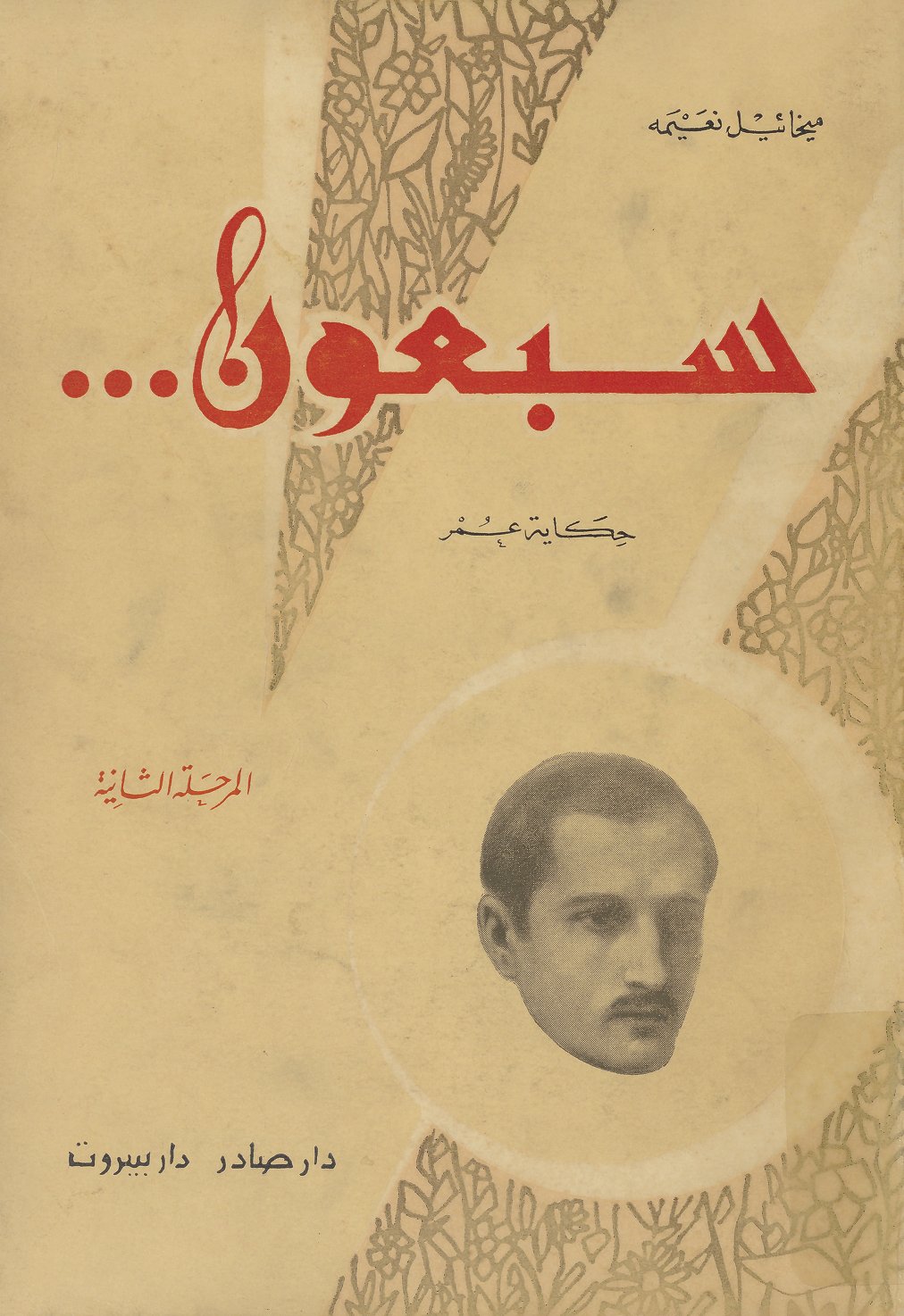

In the work, often considered controversial, he reveals certain details about Gibran’s life and personality that paint a different picture of the image that the famous poet-artist wanted his followers and critics to believe about him, and whether or not true, we have no proof of it except the author’s word. When said biography came out , many other Gibran’s acquaintances and colleagues tried to defend his memory, like Ameen Rihani (1876-1940), according to whom such private information should have been kept unsaid. Naimy justified himself replying that his aim was to portray a man of flesh and blood, with desires and physical needs, and not the prophet and/or the perfect being that thousands of people thought he was – and to praise his struggle to transcend his human faults and vices. In the second volume of his autobiography Sab‘un: Hikayat ‘umr (Seventy: Story of a Lifetime), published in Beirut in three volumes between 1959 and 1960 (Vol. I, his life up to the end of his sojourn in Russia, in 1911; Vol. II, his life in the USA, 1911-1932; Vol. III, his life in Lebanon, 1932-1960),[1] Naimy returns to talk about Gibran. Selections of the book have been recently translated from the original Arabic into English by George Nicolas El-Hage, a Lebanese American poet, professor, linguist and writer.[2] Here below is a transcription of some pages where a 70 year old Naimy remembers Gibran the man.[3]

, many other Gibran’s acquaintances and colleagues tried to defend his memory, like Ameen Rihani (1876-1940), according to whom such private information should have been kept unsaid. Naimy justified himself replying that his aim was to portray a man of flesh and blood, with desires and physical needs, and not the prophet and/or the perfect being that thousands of people thought he was – and to praise his struggle to transcend his human faults and vices. In the second volume of his autobiography Sab‘un: Hikayat ‘umr (Seventy: Story of a Lifetime), published in Beirut in three volumes between 1959 and 1960 (Vol. I, his life up to the end of his sojourn in Russia, in 1911; Vol. II, his life in the USA, 1911-1932; Vol. III, his life in Lebanon, 1932-1960),[1] Naimy returns to talk about Gibran. Selections of the book have been recently translated from the original Arabic into English by George Nicolas El-Hage, a Lebanese American poet, professor, linguist and writer.[2] Here below is a transcription of some pages where a 70 year old Naimy remembers Gibran the man.[3]

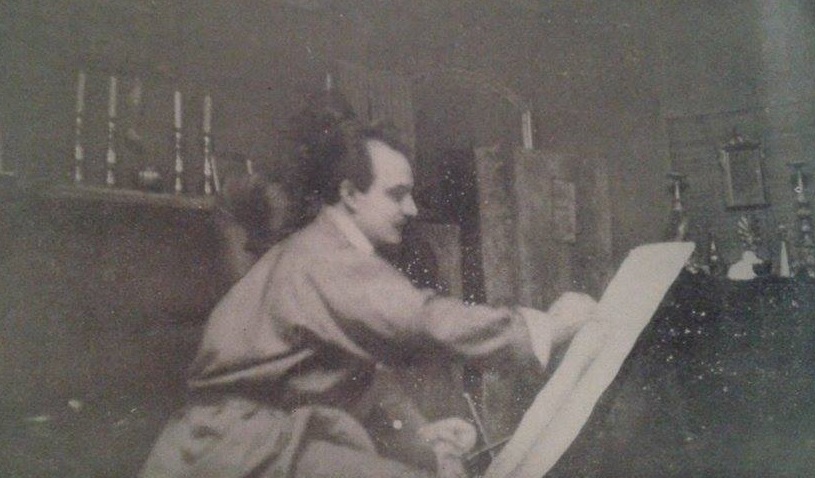

Kahlil Gibran was from Bisharri, Lebanon. He was short and well built, low-key, and discreet, with long eyelashes, and dreamy eyes. His eyebrows were arched, and his face was handsome. He was extremely sensitive, with acutely perceptive taste and a sharp imagination. He was modestly dressed, but a bit different and uncommonly attired like wearing a hat, or a necktie, or a ring which he wore on his index finger. In his walk, you detected pride. In his voice, you sense manhood and strength, and in his speech, you noticed deliberateness. When he talked, even about the most trivial of topics, he tried to avoid the most common and mundane expressions and metaphors, making his speech intermittent and anything but spontaneous. The closest of metaphors to his taste were those that were ambiguous and bore various interpretations.

If you sat and conversed with him, you would find him to be the epitome of kindness, honesty, and diplomacy, but if you betrayed a word, a movement, or a sign that he could misconstrue as an affront to his dignity or an indication to diminish the high status to where he liked to elevate himself, he would quickly turn into a volcano of rage and anger. This explains his love for praise and veneration and his disdain for criticism in spite of his pretension to be humble and casual about such matters. This also explains his tendency to weave mysterious auras and secrets concerning his behavior, his upbringing, and his family background.

He was able to make Naseeb Arida believe that he was born in Bombay, India,[4] and to convince Mary Haskell that his father was an extremely important man who could shake the foundations of Lebanon if he put his foot down and took a stand regarding any significant matter,[5] and that the church had excommunicated him and burned his book in the Burj Square in downtown Beirut,[6] and that his physical prowess was such that in a moment of anger caused by a rude visitor, he was able to rip the telephone directory in a single pull.

The fact is, the telephone directory in New York City was a big book, at least eight centimeters thick, if not more. However, in spite of all this, Gibran was rich in his friendships, and loyal to his friends. He excelled in telling jokes and appreciated good humor, even if it was full of exaggeration. Moreover, he loved cigarettes and drinking; however, I saw him drunk only once when I helped him get into a cab and also helped him get out of it later. Because Gibran was the only one among the members of al-Rabita al-Qalamiyya who devoted his entire time and energy to literature and art, and because his enthusiasm for his career was boundless and infinite, his passion was contagious, and it inspired the rest of his colleagues to intensify their efforts and increase their production.

[1] Cf. Nadeem Naimy, The Lebanese Prophets of New York, Beirut: American University of Beirut, 1985, p. 100.

[2] See his website: http://www.georgenicolasel-hage.com

[3] Mikhail Naimy, Sab‘un (Seventy): An Autobiography, Selections Translated into English with an Introduction by George Nicolas El-Hage, Ph.D., 2020, pp. 222-225.

[4] Cf. Robin Waterfield, Prophet: The Life and Times of Kahlil Gibran, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998: “Al-Funoon (The Arts) […] provided the context for one of Gibran’s more notorious public lies. When Arida asked him for biographical information to publish in the paper, Gibran gave it and Arida wrote it up in the September 1916 issue of the paper exactly as he was given it: ‘Gibran was born in the year 1883 in Bisharri, Lebanon (though some say in Bombay, India)…’ […] At first I thought that he must have been trying to cash in on the wave of Indophilia that was sweeping America in the wake of Rabindranath Tagore’s triumphal visit in 1916, but Al-Funoon went out only to the Arab populace, so that hypothesis will not do. It seems that he just wanted to cloak himself in the mystique of having a mysterious birth” [Editor’s note].

[5] Cf. for example Mary Haskell’s private journal, March 24, 1911 and April 11, 1915 [Editor’s note].

[6] Sahat al-Burj (The Tower’s Square) was the historical central public square of the town of Beirut. It is known today as Sahat al-Shuhada (Martyrs’ Square). On Gibran’s excommunication, cf. Joseph Nahas, “The Orphanage,” in Seventy-Eight and Still Musing: Observations and Reflections. With Personal Reminiscences of Gibran as I Knew Him, Hicksville, New York: Exposition Press, 1974, pp. 50-52 (https://www.kahlilgibran.com/68-gibran-on-his-excommunication.html) [Editor’s note].