-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

By Glen Kalem - Habib

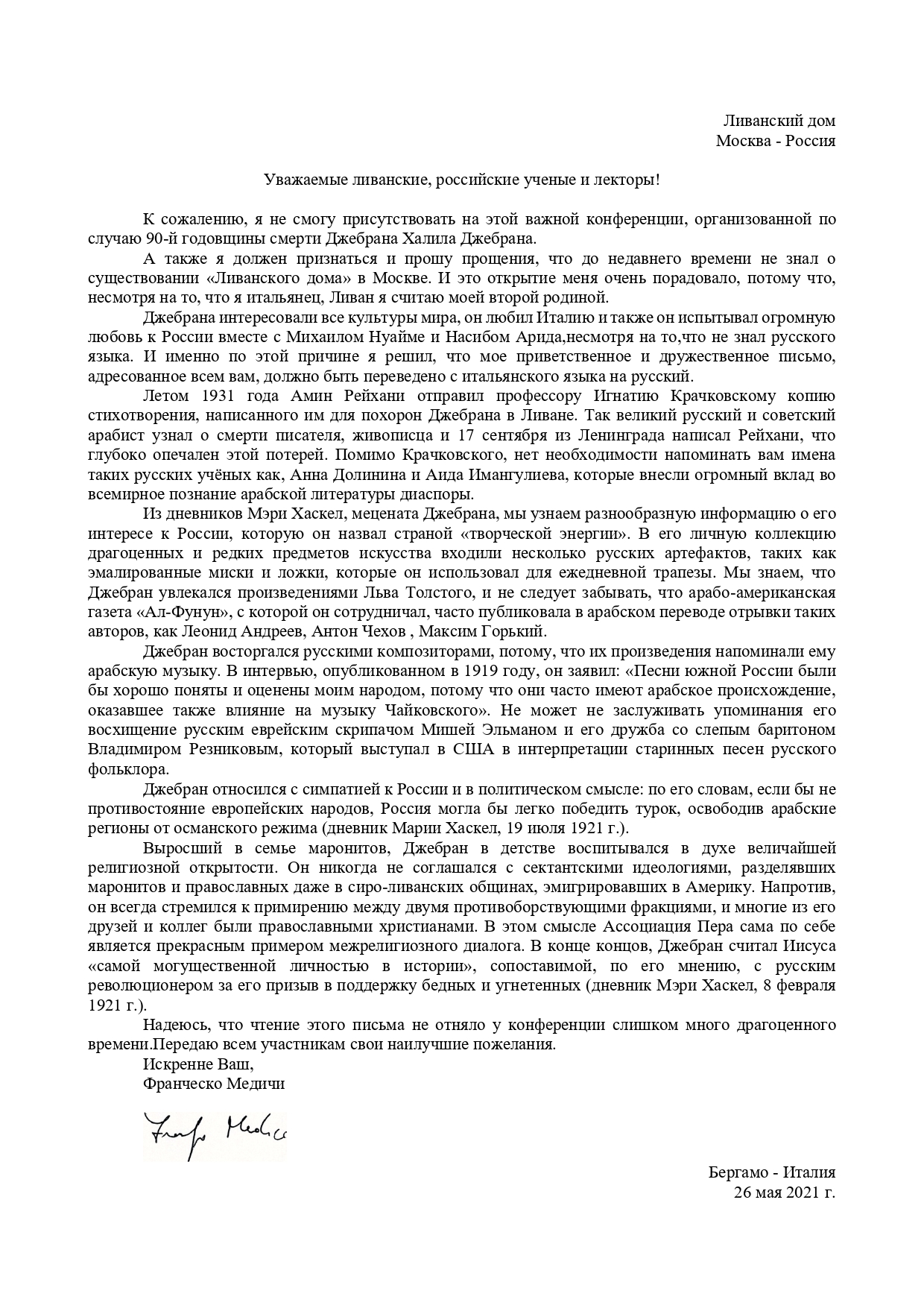

On May 26, 2021, during the opening ceremony of an International Conference organized by the Lebanese House (Al-Bayt Al-Lubnani) in Moscow, a symposium dedicated to the 90th anniversary of Kahlil Gibran's death, a letter by Italian researcher Francesco Medici was read by Dr Mishal Khaddaj, executive secretary of the above-mentioned association. Addressing participants via Zoom the letter was translated for this occasion from the original Russian into Arabic.

READ MORE: Kahlil Gibran International Conference - Russia (May-June 2021)

Here below is the transcript of Medici’s letter in its English translation:

Esteemed Lebanese and Russian scholars and lecturers.

Unfortunately, I will not be able to attend this important conference organized on the occasion of the 90th anniversary of the death of Kahlil Gibran.

I must confess – and I apologize for this – that until recently I did not know about the existence of the Lebanese House in Moscow. Such a discovery made me very happy because I consider Lebanon my second home despite the fact that I am Italian.

Gibran was interested in all the cultures of the world. Just as he loved Italy, he also felt a great love for Russia, (as did his friends) Mikhail Naimy and Nasib Arida; even though he did not speak the Russian language. For this reason, I decided that my welcome and friendly letter addressed to all of you should be translated from Italian into Russian.

In the summer of 1931, Ameen Rihani sent Professor Ignaty Krachkovsky a copy of a poem he had composed for Gibran’s funeral in Lebanon. This is how the great Russian and Soviet Arabist learned about the death of the writer-painter, and on September 17 from Leningrad, he wrote to Rihani that he was deeply saddened by that loss. In addition to Krachkovsky, there is no need to remind you of great Russian scholars such as Anna Dolinina and Aida Imanguliyeva, who made a huge contribution to the world knowledge of the Arab literature of the diaspora.

We learn from the diaries of Mary Haskell, Gibran’s patroness, a great deal of his interest in Russia, referring to it as “creative energy.” His personal collection of precious and rare artworks included several Russian pieces, such as some enamel bowls and spoons, which he used for his daily meals. We know that Gibran was fond of the works of Leo Tolstoy, and we should not forget that the Arab-American magazine “Al-Funoon,” with which he was a collaborator, often published excerpts from great Russian authors such as Leonid Andreyev, Anton Chekhov, Maxim Gorky into Arabic.

Gibran adored Russian composers because their works reminded him of Arabic music. In a 1919 interview, he stated: “The songs of southern Russia […] would be well understood and enjoyed by my people, their origin often being Arabic. Tchaikovsky […] has felt its influence.” His admiration for the Russian Jewish violinist Mischa Elman and his friendship with the blind baritone Vladimir Resnikoff, who often performed interpretation of bygone Russian folklore in the United States, cannot go without a mention.

Gibran was also sympathetic to Russia in the political sense: according to him, if it were not for the opposition of the European powers, Russia could easily defeat the Turks, freeing the Arab regions from the Ottoman yoke (Mary Haskell, Journal, July 19, 1921).

Raised in a Maronite family, Gibran was raised as a child with the greatest religious openness. He never agreed with the sectarian ideologies that divided the Maronites and the Orthodox, even in the Syro-Lebanese communities who emigrated to America. On the contrary, he always strove for reconciliation between the two opposite factions, and many of his friends and colleagues were Orthodox Christians. In this sense, the Pen League itself is an excellent example of interreligious dialogue.

Lastly, Gibran considered Jesus “the most powerful personality in history”, comparable, in his opinion, to a Russian revolutionary for his appeal in support of the poor and oppressed (Mary Haskell, Journal, February 8, 1921)

I hope that reading this letter did not take too much precious time from the conference. I send my best wishes to all participants.

Yours sincerely,

Francesco Medici

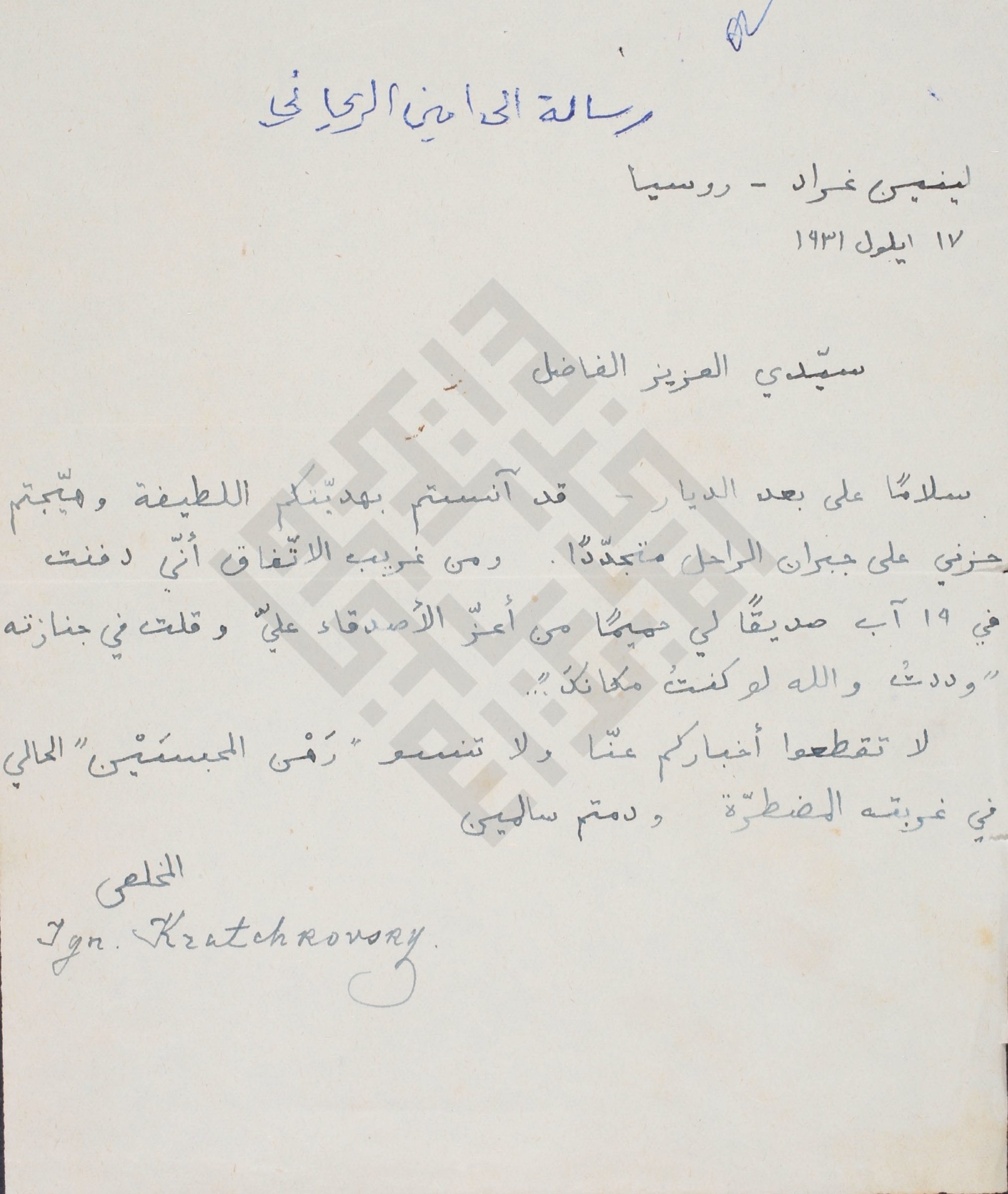

Medici mentions the member of the Russian Academy of Science Ignaty Yulianovich Krachkovsky (1883-1951), who was one of the founders of the Soviet school of Arab studies. Krachkovsky’s original Arabic letter to his friend Rihani is preserved by the ARO (Ameen Rihani Organization) and a scanned copy of it can be found in the Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies digital archive. It was translated into English by George Nicolas El-Hage, a Lebanese American poet, professor, linguist and writer, and published in his 2015 book Selected Letters of Ameen al-Rihani:

Leningrad – Russia

September 17, 1931

Dear Honorable Sir,

Greetings and peace to your far away homeland.

You have honored me with your kind gift [i.e. Rihani’s Eulogy for Kahlil Gibran] and at the same time reignited my grief and sorrow over the death of Gibran. It is one of the strangest coincidences that on the 19th of August I have buried one of my closest and dearest friends, I also said during his funeral: “I wish to God that I had died instead of him.”

Please continue to send me your news and do not forget the current “prisoner of the two dungeons” in his forced exile.

Stay safe,

Sincerely,

Ignaty Krachkovsky

The Russian