by Francesco Medici

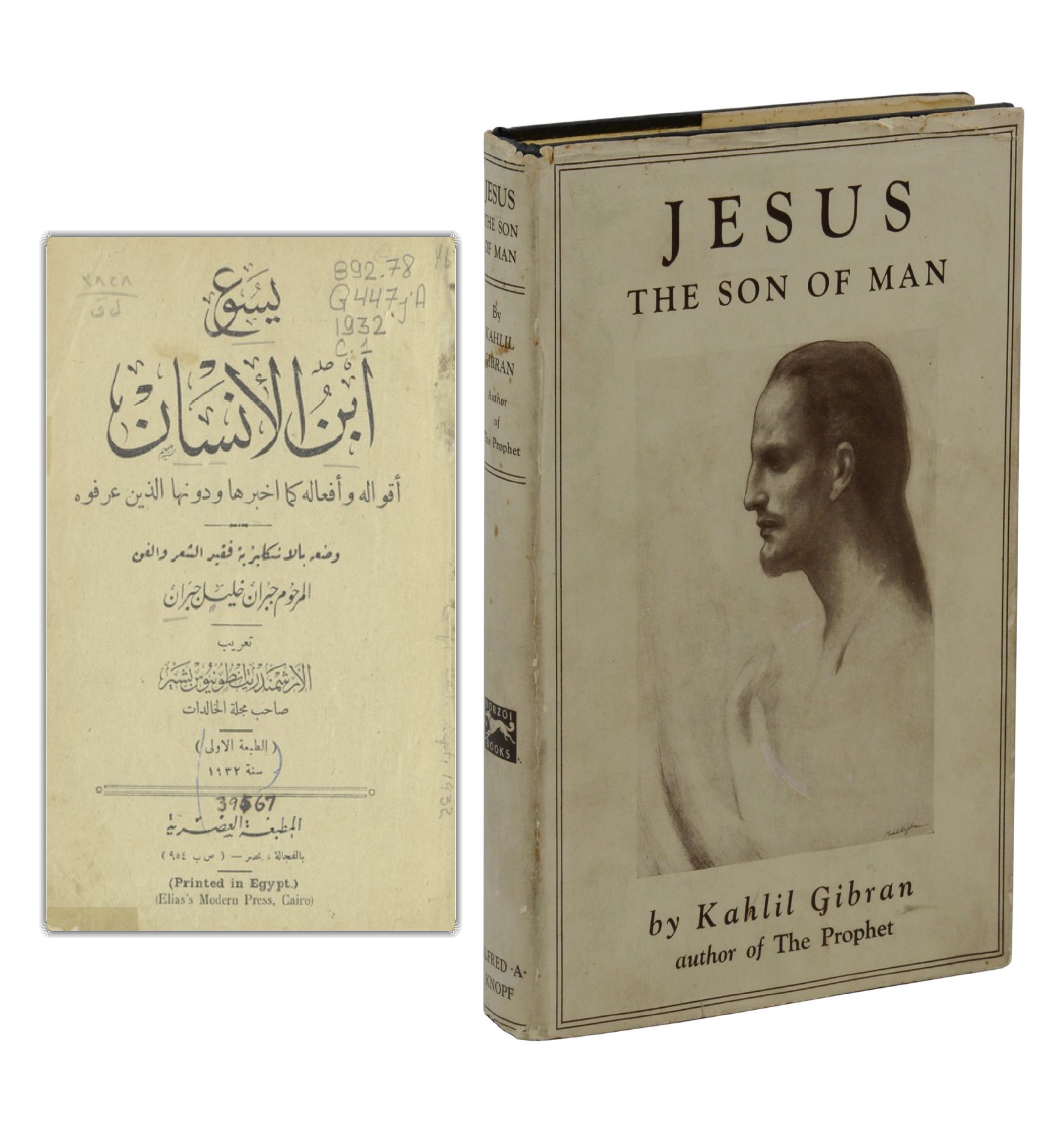

Kahlil Gibran wrote his longest book, Jesus the Son of Man: His Words and His Deeds as Told and Recorded by Those Who Knew Him, in a little over a year between 1926 and 1927 and New York publisher Alfred Knopf published it in the fall of 1928. Actually, the figure of Jesus had already appeared in Gibran’s writings and art in various forms. He also often told his patroness Mary Haskell that he had recurring dreams of him and mentioned wanting to write a life of Jesus in a 1909 letter to her.

Around 1926, Gibran said to his close friend and colleague Mikhail (‘Mischa’) Naimy once after Sand and Foam[1] was out:

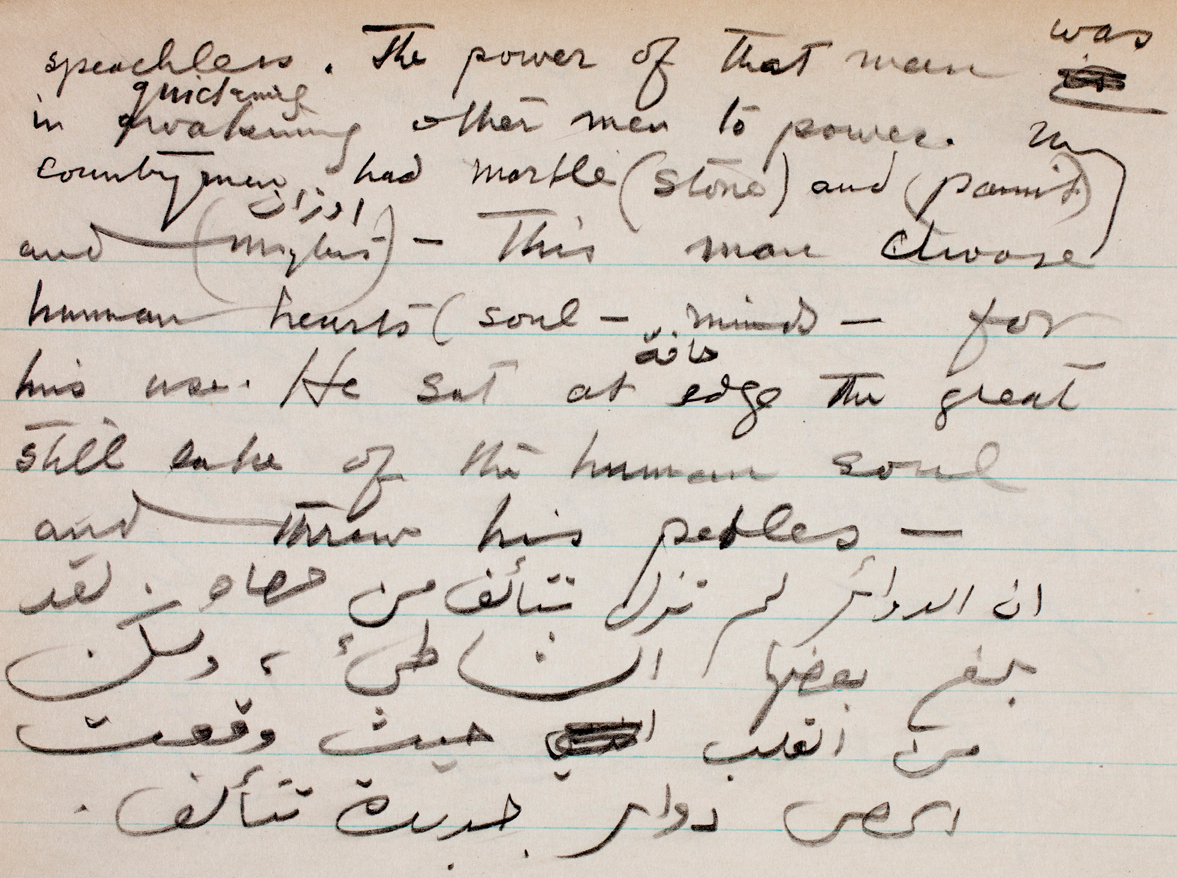

What do you say of a book on Jesus? Jesus has been haunting my heart and my imagination for some time past. I am sick and tired, Mischa, of people who profess to believe in him, yet always speak of him and paint him as if he were but a sweet lady with a beard. To them he is beautiful, but lowly, humble, weak and poor. I’m also weary of those that deny him, yet present him as a sorcerer or an imposter. Still more weary am I of ‘the scholars’ who are ever digging into antiquity to produce lengthy and stupid arguments either for or against the historicity of his personality which is the greatest and most real personality in human history. What shall I say of the senile juggleries of theologians which make of Jesus a sort of a hybrid, half-God and half-man? My Jesus is human like you and me. A certain American writer was even so brazen as to portray him as a clever business man whose deeds and teachings had nothing else in view but cold material profits. Just think! To me he was a man of might and will as he was a man of charity and pity. He was far from being lowly and meek. Lowliness is something I detest; while meekness to me is but a phase of weakness. [...] I propose to have a number of Jesus’ contemporaries speak of him, each from his own point of view. Their views combined will bring out the portrait of Jesus as I see him. The scheme will be in perfect harmony with my style.[2]

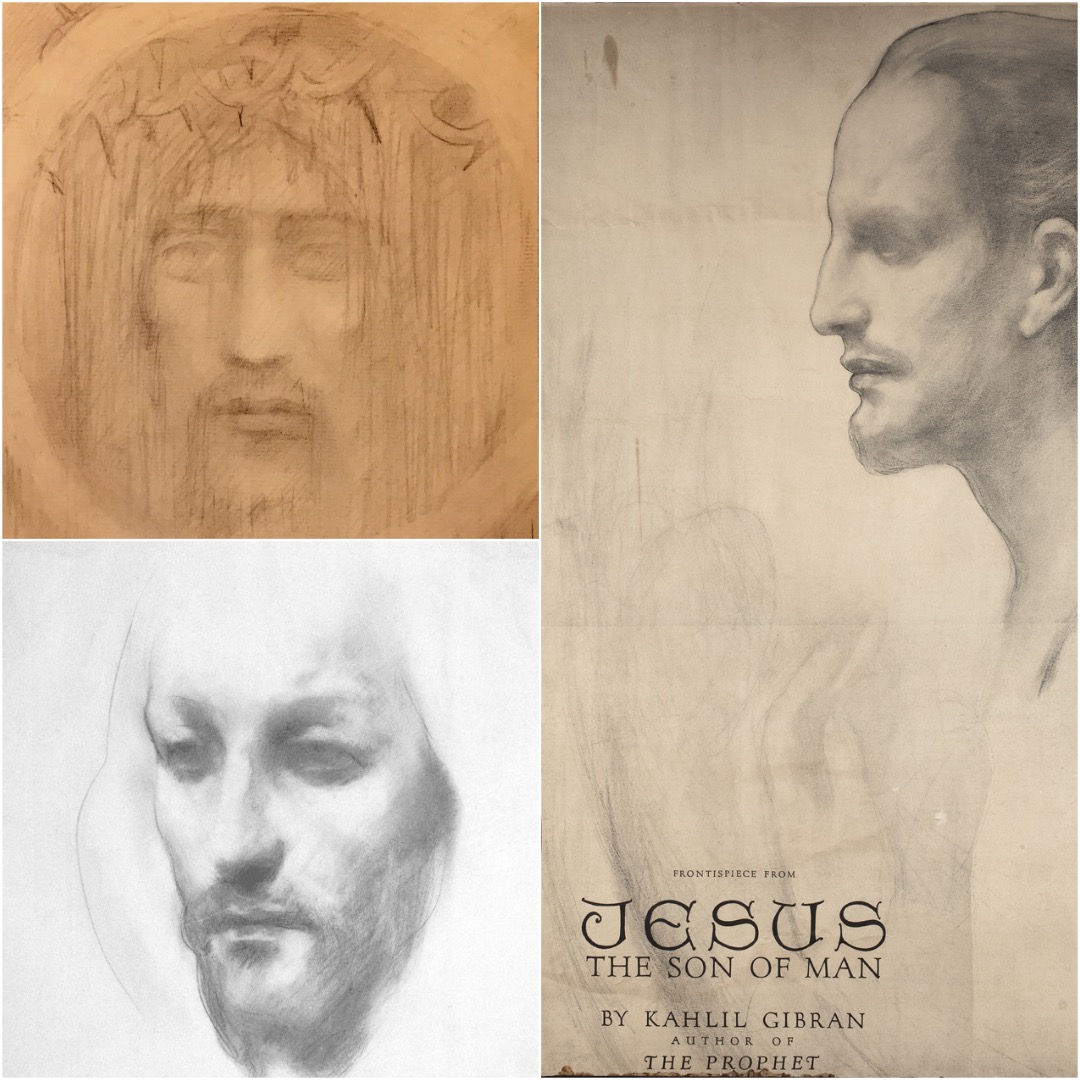

The work’s structure is indeed clear and simple: seventy-eight people who knew Jesus – some real, some imaginary; some sympathetic, others hostile – tell of him from their own personal perspective. It was the most lavishly produced of Gibran’s books, with some of the illustrations in color. The reviews were strongly and uniformly favorable, and the book has remained the most popular of his works next to The Prophet.

On 24 November 1928, «The St. Louis Times» published a piece by Margaret Statler entitled Untrue Versions of Jesus Caused Gibran’s Volume. The reporter asserted that she went to Gibran’s New York studio expressly to ask him: «Why did you write the book, Jesus the Son of Man?». The following perhaps, tongue in cheek exchange, was recorded, and we can assert from Gibran’s well-crafted question and answer dressing of the reporter, he was also educating her as well:

Before I tell you why I wrote the book, Jesus the Son of Man, I want you to imagine yourself, an American, living in a far land called Syria. You have lived there so long that you know the language of that country and other neighboring countries, which is Arabic.

And then I want you to imagine numerous books written by Syrians, Arabs, Lebanese, Egyptians, and Persians on the life of Abraham Lincoln. You read these books and though you know that their authors are sincere… your heart cries out saying, «This is not my Lincoln. This is not our great American. This is not the man who freed a race from bondage. This is not the man with a sweet, patient sense of humor. These people are making caricatures of our ‘Father Abraham.’ They have not hear his real voice. And the translation of his address is an insult, not only to the man who wrote the Gettysburg address but to us all who deem this expression a masterpiece in the English language. They have painted him pretty when he was virile and strong. They have ironed out or distorted his countenance so that he has become merely another suave politician with a very high hat.»

Imagine all these things, and to it all listen to those men of the Near-East who say: «There was no such man as Abraham Lincoln,» or, «He is but a myth,» or, «If he did exist at all he was a very good business man, and a good self-advertiser,» or, «Abraham Lincoln’s desire to free the slaves of North America was only the result of his having loved a fascinating mulatto,» or «his passion to retain the unity of our country was a form of tyranny. For why should not every State be a commonwealth, independent and alone?»

He ends with.

Now I, a Syrian, have lived here in America many years, and I happen to know two or three Occidental languages in which both men and women have written about Jesus. And there came a day when my heart cried out, and I had no longer the patience with those who, for generations, had been distorting the Great Man who had happened to be born by the grace of God in my own country, distorting His noble face, misquoting His speech, and turning His song of joy into a lament. Someone has said of Lincoln that he was Jesus in miniature, and that is a great tribute to Lincoln, if we are to consider the work and the influence of the one in comparison with the work and influence of the other.

Surely you men of Western world would not see that beautiful miniature made into a caricature by those who love Lincoln, but do not understand him, and who, either for sport or for a passing comfort, exhibit that miniature as a work of art, nay, even as a religion. And surely you, in fairness, would not have me see Jesus the Nazarene in caricatures of all descriptions.

[1] The book, published by Knopf in New York in 1926, is a rich collection of aphorisms that includes two of the most famous Gibran’s sayings on Christ: «Once every hundred years Jesus of Nazareth meets Jesus of the Christian in a garden among the hills of Lebanon. And they talk long; and each time Jesus of Nazareth goes away saying to Jesus of the Christian, “My friend, I fear we shall never, never agree”»; «There are three miracles of our Brother Jesus not yet recorded in the Book: the first that He was a man like you and me, the second that He had a sense of humor, and the third that He knew He was a conqueror though conquered».

[2] M. Naimy, Kahlil Gibran: A Biography, with a Preface by M.L. Wolf, New York: Philosophical Library, 1985, pp. 207-208.