-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

by Francesco Medici and Glen Kalem-Habib

American publisher Alfred Abraham Knopf (1892-1984) along with his wife Blanche Wolf (1894-1966), both born to a Jewish family, founded Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. in New York City in 1915. The publishing house, which would bring out the best of North and Latin American, European, and Russian literature, soon became famous all over the world for its special attention to the quality of content, presentation, printing, binding, and design in his books.

Knopf published not only all of Kahlil Gibran’s original English works – The Madman (1918), The Forerunner, (1920), The Prophet (1923), Sand and Foam (1926), Jesus, the Son of Man (1928), The Earth Gods (1931), The Wanderer (1932, posthumous), The Garden of the Prophet (1933, posthumous) –, but also Prose Poems (1934, translated from the Arabic by Andrew Ghareeb), A Tear and a Smile (1950, translated from the Arabic by H.M. Nahmad), the biography by Barbara Young This Man from Lebanon. A Study of Kahlil Gibran (1945) and the epistolary exchange Beloved Prophet: The Love Letters of Kahlil Gibran and Mary Haskell, and Her Private Journal (1972).

After World War II, Knopf began receiving from a Syrian American, Anthony Rizcallah Ferris, English translations of early Arabic-language works of Gibran’s that the firm had not known existed. The first was a translation of al-Ajniha al-Mutakassira (1912). Although the firm did not think that the translation was very good, it offered Ferris a contract. Knopf never published Ferris’ translation, which was ultimately brought out by New York Citadel Press in 1957 as The Broken Wings. The firm rejected Ferris’ second submission outright – i.e. Tears and Laughter, translation of Kitab Dam’a wa’btisama (1914) – and tried to discourage him from seeking another publisher.

Behind the scenes, Alfred Knopf was working aggressively to maintain the firm’s position as the exclusive American publisher of Gibran’s works. He cabled the Gibran National Committee, asking it to identify and supply the firm with copies of all of Gibran’s early Arabic publications and seeking its advice on finding a different translator.

This instigated an intense exchange between the then-president of the Gibran National Committee Mr. Habib K. Kayrouz, between the months of February and March 1946. The letters shared with the publisher regarding Gibran’s complete Arabic bibliography fervently pointed to the unknown name (at least to Knopf) of Mikhail Naimy, «who is at present in Lebanon,» as

«the only living person whose judgment we trust without a reserve in everything concerning Gibran’s works, both English and Arabic.»

Knopf thought he had finally found the right man whom he was searching for. In a letter dated 15 March 1946, he wrote to Kayrouz:

«We note with interest what you say about Mr. Mikhail Naimy and would like to know if he is competent himself to translate into English these early books by Gibran, and to supply with the translation, in English, the necessary commentaries, biographical and critical, which you mention. If so, we should like very much to see a sample translation by him from such a work.»

The letter from Naimy to Knopf dated 27 May 1946, whose content is provided below, is a rare and extremely precious document in which the writer, although kindly rejecting to translate Gibran’s Arabic works into English, talks about his deep friendship and artistic partnership with Kahlil, and express his severe judgement both on the Arab publishers of those works and on the works themselves.

Dear Mr. Knopf,

Mr. Habib Kayrouz, president of the Gibran Committee, showed me your letter in which you express the desire to have me translate for you one or two of Gibran’s early Arabic pieces. He also requested me to communicate with you regarding this matter. Perhaps I should begin by telling very briefly of my relations with Gibran.

From 1916 up to his death Gibran and I were inseparable companions. Having organized in 1920 “Arrabitah” – The Pen Bond – with him as president and myself as secretary, and begin of similar trend of thought and much the same literary taste, we worked hand in hand until we brought about what is justly considered by all students of Arabic as a revolution in Arabic literary forms and currents. I was the only one of his Lebanese and Syrian friends present at his bedside during his last hours at the St. Vincent’s Hospital. I came back to this country [Lebanon] a year after my friend’s passing, and in 1934 I brought out in Arabic the only comprehensive biography of him, – a book of some 300 pages, – now considered a classic.[1]

During our life in New York Gibran rarely wrote anything, whether in Arabic or English, which he did not read to me before being published. Like-wise I read to him what I wrote. His usual autograph of his books to me was: “To my beloved brother and companion.” I still treasure about twenty of his personal letters to me, many of them quite intimate and revealing. You can readily see how deep is my knowledge of Gibran and all his Arabic and English works.

Now, when Mr. Kayrouz told me of the difficulty you were experiencing with a translator of some of Gibran’s early Arabic productions I, out of loyalty to my late friend, volunteered to pass on the authenticity and quality of any such translations, but not to do the translating myself. Many unscrupulous publishers in the Arabic East have brought out editions of this or that of Gibran’s Arabic books inserting into them pieces that are not at all Gibran’s, aside from their numerous typographical errors.

Personally, my own work leaves me no time to devote to translating, I am so far the author of a dozen Arabic books and two English ones still manuscript form. But to help you and the Gibran Committee out of a difficulty, and to serve my friend’s memory, I can find the time to pass on any translations that may be submitted to you, should you desire me to do that. Such labor I am glad to offer gratis. Mr. Andrew Ghareeb when translating “Prose Poems” often came to me for help and advice.

I must add that most of Gibran’s Arabic works as yet untranslated into English are much inferior in quality to his later and maturer English works. But a passably good anthology can be culled from them by one who is a student of Gibran’s Arabic and English and a fairly good master of both languages.

With my best wishes to you, dear Mr. Knopf, I remain,

Very faithfully,

Mikhail Naimy

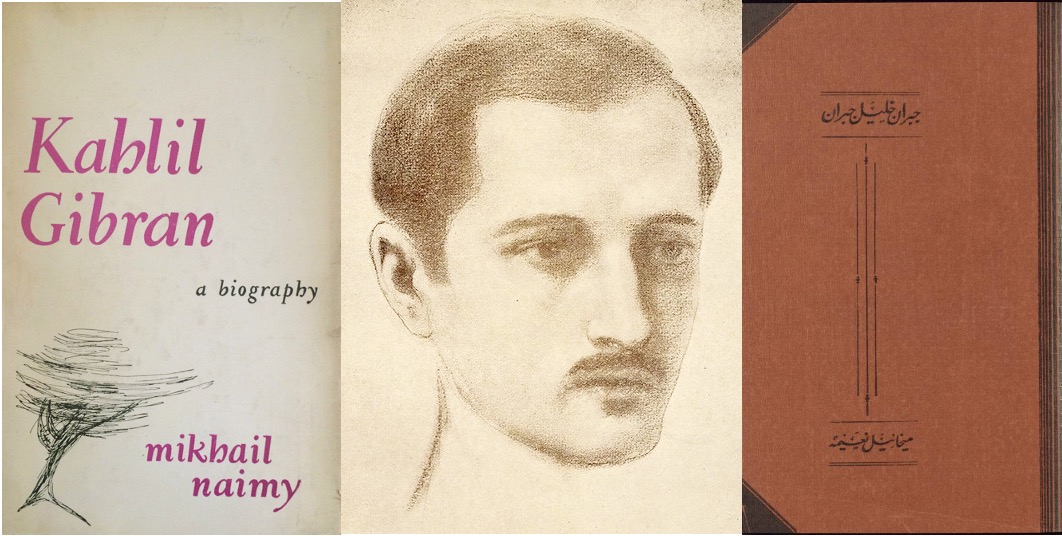

[1] Jubran Khalil Jubran: hayatuhu, mawtuhu, adabuhu, fannuhu (Kahlil Gibran: His Life, Death, Literature, and Art), Beirut: Matbaʻat Lisan al-Hal, 1934 (English version: Kahlil Gibran: A Biography, New York: Philosophical Library, 1950).