-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

By Glen Kalem-Habib and Francesco Medici

all rights reserved Glen Kalem-Habib copyright © 2023

As The Prophet celebrates its 100th year of publication this year, many will once again acknowledge its well-deserved accolades and records. However, the enigma surrounding its enduring popularity still persists, and even after a century of readership and publishing, we continue to uncover its secrets.

This article was inspired by Francdesco Medici's earlier research, which led to the publication of the insightful article "Translating Gibran's Early Arabic Books: An Unpublished Letter of Mikhail Naimy to Alfred Knopf," revealing some fascinating details in an extraordinary letter that Gibran's close friend and biographer, Mikhail Naimy, wrote to the esteemed publisher Alfred Knopf.

Surprisingly, Knopf had been unaware of Gibran's translated and subsquently published Arabic works into English until the 1950s, to which he eagerly sought Naimy's expertise to translate (better versions) and publish them under his own firm.

The fact that Gibran had the freedom to create his own book cover and even the publisher's logo piqued our interest as I ventured into uncharted research territory to examine the relationship between Gibran and his English publisher Knopf. The outcome of this exploration proved to be immensely fulfilling.

This reserarch revitalized the lingering questions that both Francesco and I had contemplated with curiosity for years, as historical context had been scarce. Today, we can illuminate this matter and proudly unveil a newfound revelation regarding Gibran and his association with the much famed Borzoi.

The exact reason behind Gibran being bestowed the honor of creating his own interpretation of the Knopf colophon has always remained an enigmatic question, void of a definitive answer. But today we can reveal he stands as the inaugural, and quite possibly the sole, A. A Knopf author to be granted such an exceptional privilege.

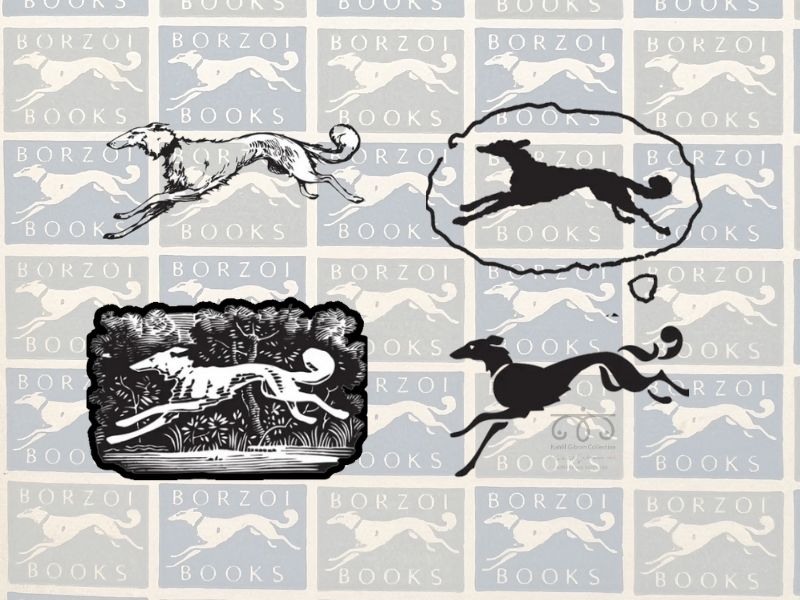

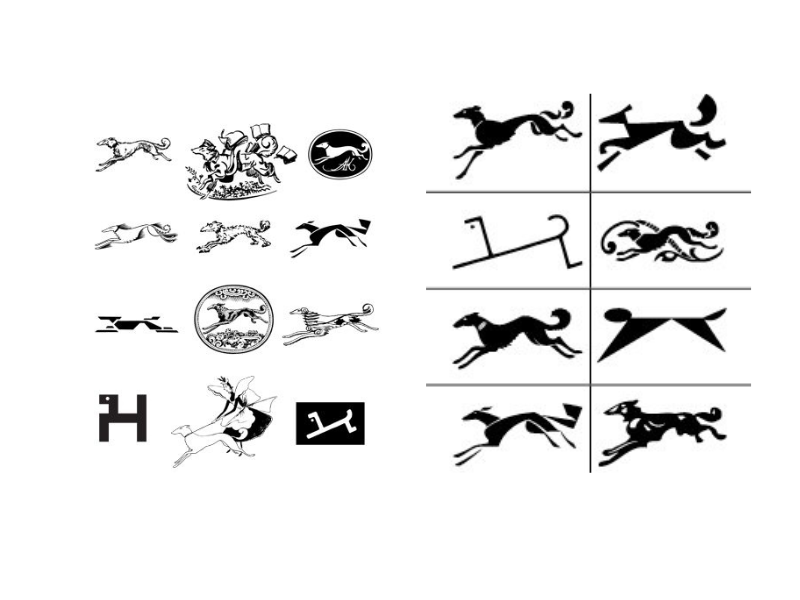

The story of the Borzoi, a Russian hound dog, which had become synonymous with the publisher's prestigious legacy, adorning all of A. A Knopf's books and serving as their trademark emblem, as it does to this day has revealed a distinct historical narrative when it intertwines with Gibran.

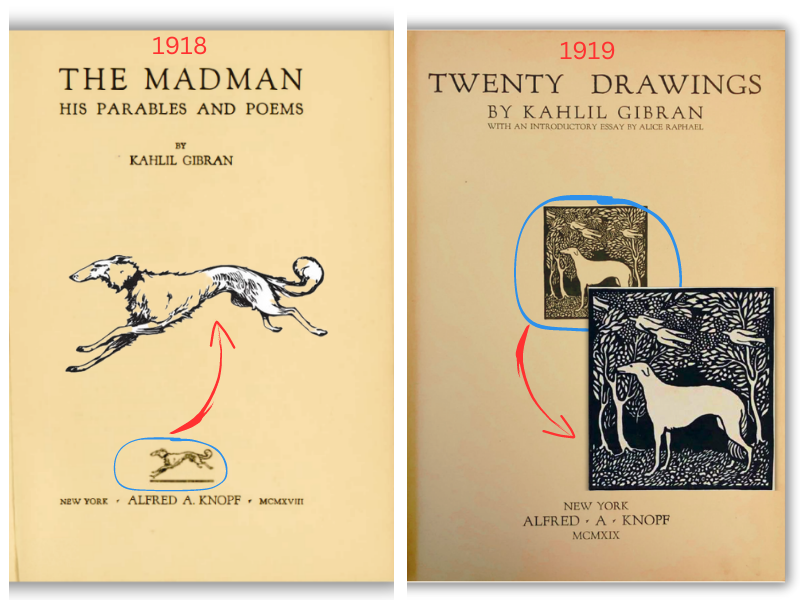

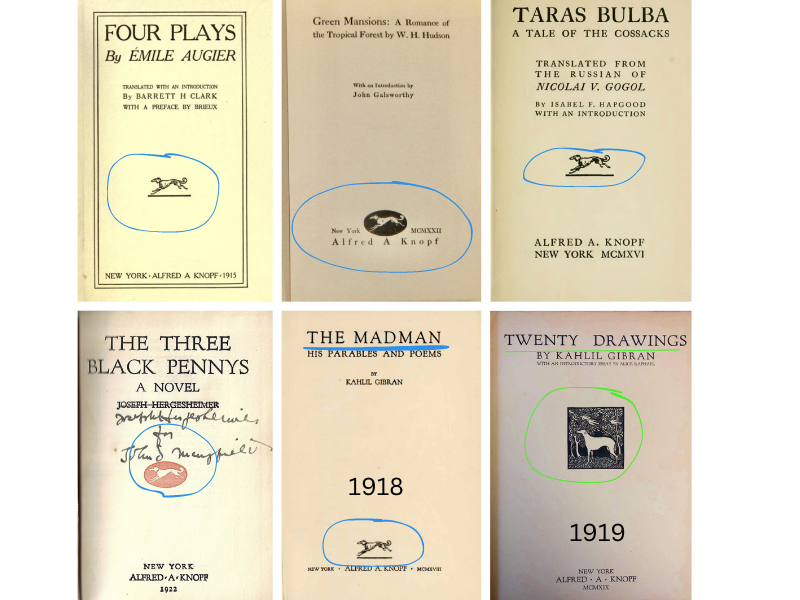

With a little digging and some help from our friends at Knopf–DoubleDay and the ever helpful archivist at the Harry Ramson Center in Texas University, we can now reveal that Gibran’s own illustration of the publishers insignia, was in fact uniquely attributed to him, who not only was the first to be afforded this privilege in his publication of Twenty Drawings (1919); a few short years after Knopf was founded, but as it turns out, no other author in the history of the publishing firm, was afforded the same honor since.

With a little digging and some help from our friends at Knopf–DoubleDay and the ever helpful archivist at the Harry Ramson Center in Texas University, we can now reveal that Gibran’s own illustration of the publishers insignia, was in fact uniquely attributed to him, who not only was the first to be afforded this privilege in his publication of Twenty Drawings (1919); a few short years after Knopf was founded, but as it turns out, no other author in the history of the publishing firm, was afforded the same honor since.

According to the Harry Ramson Center there is near to 150 recorded Borzoi designs in thier library and most were all but designed by the publisher, (or contract designers) and not the authors, this makes Gibran’s Borzoi a one-off! and if that wasn’t a grand compliment, it also turns out he was the first to ever design and illustrate his own book covers; another first in the history of one of the most successful publishing companies in the world, now owned by Penguin-Random House.

Knopf v’s Wolf.

Alfred and wife Blanche nee Wolf, who co-founded the publishing company with Alfred was a bitter spouse. Blanche Wolf often considered the ‘soul of the company’ in a recent memoir by Laura Claridge THE LADY WITH THE BORZOI states that she was not afforded the solemn promise in 1916 made by her then courting husband Alfred, when he promised, that her maiden name ‘Wolf’ would be associated with the publishing firm. Coming from a well to do publishing family herself, and known as a superb editor, visionary for new authors, a chic dresser and dog lover, she is also credited with choosing and designing the Borzoi; the Russian wolfhound imprint marking all of Knopf titles and which the firm is to date associated with. It is not at all surprising that the memoir also reveals and credits her, (and not Alfred) as the one who discovered Kahlil Gibran.

“the books that kept Knopf afloat through the years were The Prophet, Kahlil Gibran’s collection of uplifting spiritual koans, Dashiell Hammett’s detective novels, and Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking – all brought in primarily by Blanche.”

(Joanna Scutts / April 2016, New Republic)

The memoir also touches on Alfred Knopf's lack of confidence with Gibran's poetry and its unlikley readership. Considering the disappointing sales of Gibran's initial Knopf publication, "The Madman," in 1918 the ambitous new publisher might have began questioning whether signing the poet was a worth it. It's possible that his decision was influenced by his wife Blanche as well as other Knopf employees/writers of that time, such as Witter Bynner and Claude Bragdon, who were all mutual friends of Gibran.

The extent of the gamble and uncertainty surrounding the signing is captured in a recent exclusive email I received from Robert Gottlieb, the former editor-in-chief and ex-president of A.A. Knopf from 1968 to 1987, where he discusses The Prophet and Alfred Knopf's doubts.

According to Robert, during his tenure, he never had any direct contact with anyone from "Gibran-land," as he puts it. He does recall, however, that at the "peak of the Gibranmania" craze, they were selling an impressive "400,000 copies" of The Prophet annually.

What makes this achievement even more remarkable is that the book had "never been advertised" and was believed to have been acquired based on a ‘tip’ for a mere "couple of hundred dollars". A tip that surely paid huge dividends and elevated Knopf to become the publishing giant it is today.

Observing the evolution of Gibran's Borzoi colophon following his initial Knopf publication, The Madman, in 1918, resembled the colophons of other authors during that period. However, with the release of his second Knopf book, Twenty Drawings, in 1919, Gibran introduced his own interpretation of the Borzoi, which subsequently appeared in all his future Gibran-Knopf publications. Unlike the dynamic 'dashing' version commonly found on Knopf books, Gibran's rendition depicted a serene stationary creature with its tail gently pointed downwards, nestled among trees and gazing at the birds soaring above.

The precise origins of how this came about remain obscure, leaving behind unanswered questions for a later time. Regrettably, an office relocation in 1945 accelerated the destruction of numerous older files, leaving scant remnants of the firm's pre-1945 correspondence. However, it does seem that Gibran's Borzoi was the first of its kind crafted by an author. Book designers, like Boris Artzybasheff, employed by Knopf was credited for some designs, but most were essentially conceived by the publisher.

Though existing research does not definitively confirm Gibran as the absolute first, an exploration of other knopf published works during the period between 1915 and 1919 strongly indicates his status as one of the earliest. Most of the initial authors mentioned in our research were either deceased during this timeframe or not exclusively associated with Knopf, as their works were simply republished under the Knopf label. Therefore, it is reasonable to assert that the initial ten books published by Knopf in 1915 predominantly comprised of Russian translations sourced from "London Sheets," making it highly unlikely for these authors to have individually designed their own Borzoi. However, as subsequent years witnessed the publication of an additional 29 books in 1916 and another 37 in 1918, further investigation into these books and authors is necessary to validate the claim of Gibran's pioneering status.

Initial publications

Revealing just how and why this came to pass, our answer lies in between the books of Madman and 1919's publication of Twenty Drawings, where the two significant changes were added.

When it comes to the writing and printing of his works, Gibran was notoriously picky. As careful researchers in this topic, we uncovered various distinguishing characteristics and even anomalies in his writing. We are well aware of the multilingual author's great desperation, as he constantly attended to the minutiae of typography, possibly in order to bridge a hole that existed in both his original and adoptive countries. This characteristic is highlighted when reading his diary entries and correspondences with his benefactor and editor, Mary Elizabeth Haskell, which serve as witness to his steadfast drive to endow each letter and word with an indelible essence. “carved upon it a face that no one can forget."

Gibran's careful temperament was undoubtedly appealing to Knopf, whose aim stretched beyond simply establishing a distinguished list of authors. Alfred Knopf had a unique obsession with the aesthetics of trade books, ensuring that every release had vivid dust covers, flawless bindings, and visually appealing typography. The presence of renowned book designer Claude Bragdon during the firm's first year, as well as following contributions by Elmer Adler and W. A. Dwiggins in the 1920s, demonstrate Knopf's dedication to fine design. Other renowned designers who worked on Knopf's illustrious books included Warren Chappell, Guy Fleming, Carl Hertzog, Bruce Rogers, Rudolph Ruzicka, George Salter, and Vincent Torre.

If that wasn’t enough of a challenge, he often struggled with converting his Arabic words and thought process into an equivalent English prose.

“English still fetters me. I don't think without looking for words. In Arabic I can always say what I want to say”

In another letter to Mary, Gibran expresses his need to direct the publisher’s stenographer …

“I have to learn each thing for myself, my own way. You probably think I'm finicky because I make this stenographer's copy so fussily. But you don't know what I go through later if I don't put in every comma and make every letter and mark unmistakable”

Another major factor in Gibran’s need to direct his own style of writing and moreover Bookmaking was undoubtedly linked to the fortuitous mentorship he had with Fred Holland Day. (FHD)

Fred Holland Day was a Publisher, Photographer and supporter of the Avant Guard, who nurtured the young painter’s early education, but most likely exposed him to the prestigious craft of, publishing, and bookmaking, which Day was highly noted for. This kind of exposure and learning was yet another factor that would have sparked Gibran’s fascination with the art of designing his own Borzoi.

Biographers Jean and Kahlil ‘George’ Gibran offer an insight into the driving force of FHD; how along, with his team of Harvard graduates led by Bookmaker, Herbert Copeland strived to make the publishing firm ‘Copeland and Day’ one of the most respected, reflecting the highest standard of its time.

It was run from an "aesthetic little office" at 69 Cornhill, a location famous for its bookstallish associations. From the outset, there was nothing of the playful dilettante about this venture. Copeland and Day became a serious and successful publishing house, quickly respected for introducing "a higher standard of integrity in craftmanship and in commercial standing as well as in the character of the literature issued." … the ninety-eight books that the firm issued in its five and a half years of existence pioneered the way for modern typography and bookmaking in America.

It was to be not only an expression of the most advanced thought of the time … but as well a model of perfect typography and printer's art. We had special handmade paper prepared for us, and a new and beautiful fount of type."

Besides hosting Gibran’s first ever public exhibit in 1904, it was FHD who first nurtured-molded the young Syrian Lebanese Artist with lifelong skills and knowledge that would have a profound and lasting effect, and consequently assist in his rise towards his own success as a writer/painting.

“The young Kahlil was to graft these initial and most important artistic influences onto his own” … their essences would be remembered and emulated by the young artist …As a result of what Fred Holland Day bequeathed to him”

By the year 1898 imbued with plenty of self-confidence and encouragement by his Patron, Gibran was beginning to develop his own style and technique and was permitted by his patron to work on his own illustrations, that would eventually grace some of Copeland and Day’s publications.

There is no doubting what this accomplishment would have done for Gibran, to think, it was only a three years earlier the 12 year old and his desolate family landed in Boston, from the remote and poor village of Bcherre, only now to be illustrating alongside other Copland and Day commissioned illustrators such as Will Bradley, Ethel Reed, and John Sloan.

One last clue pertaining to Gibran’s schooling at Copeland and Day came from a newspaper review about the firm published in the Boston Daily Advertiser. Apr. 27, 1892.

“indiscriminate idol-smashing… The mission … to promote a love for art and to contend for spiritual rather than material good. … a wish to reinstate U in such words as 'honor', to substitute Roman numerals for Arabic, and to spell certain words with capital letters”

This review reflected some anomalies discovered and was the subject of many discussion amongst scholars – in particular Jean Pierre Dahdah’s observation of the capitalization of certain word that perhaps didn’t need to be.

And the wonderful discover by Phillippe Marysseal who noticed the correction of certain words between the 1st print in 1923 and the 12th print in 1925 – "sleeping mother to sleepless mother" and which we previously published under the title of “And you, vast sea,...”

.

After a century of publication and readership, one certainty remains: the prophet persists in unveiling its mysteries, encompassing both the words within its text and the souls who forged it, in realms spiritual and metaphysical.

In wrapping up this article, I recall a delightful Lebanese Arabic expression, 'a term of affection' exchanged during anniversaries or birthdays: 3bal Miya! This phrase roughly signifies "may you reach the age of 100" As we reflect on Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet and its remarkable centenary, I feel a deep sense of privilege and honor to recount fragments of its remarkable journey. And now, let us extend our well wishes once more, aspiring that it endures for another 100 years!