by Francesco Medici

© Copyright Francesco Medici All Rights Reserved 2019

On the night of 11 November 1904, a devastating fire completely gutted the Harcourt Studios, located on 23 Irvington Street, Boston. The building was shared by many of the city’s most notable artists, including Edmund C. Tarbell (1862-1938), Frank W. Benson (1862-1951), William P. Burpee (1846-1940), Joseph DeCamp (1858-1923), William Macgregor Paxton (1869-1941) and Fred Holland Day (1864-1933). [1]

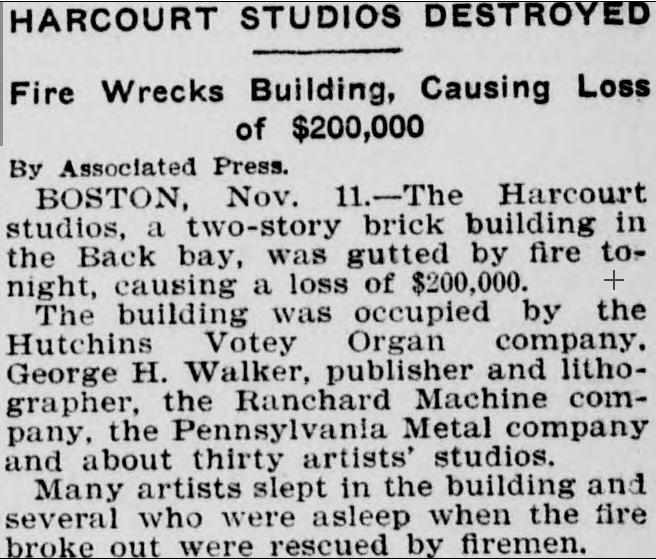

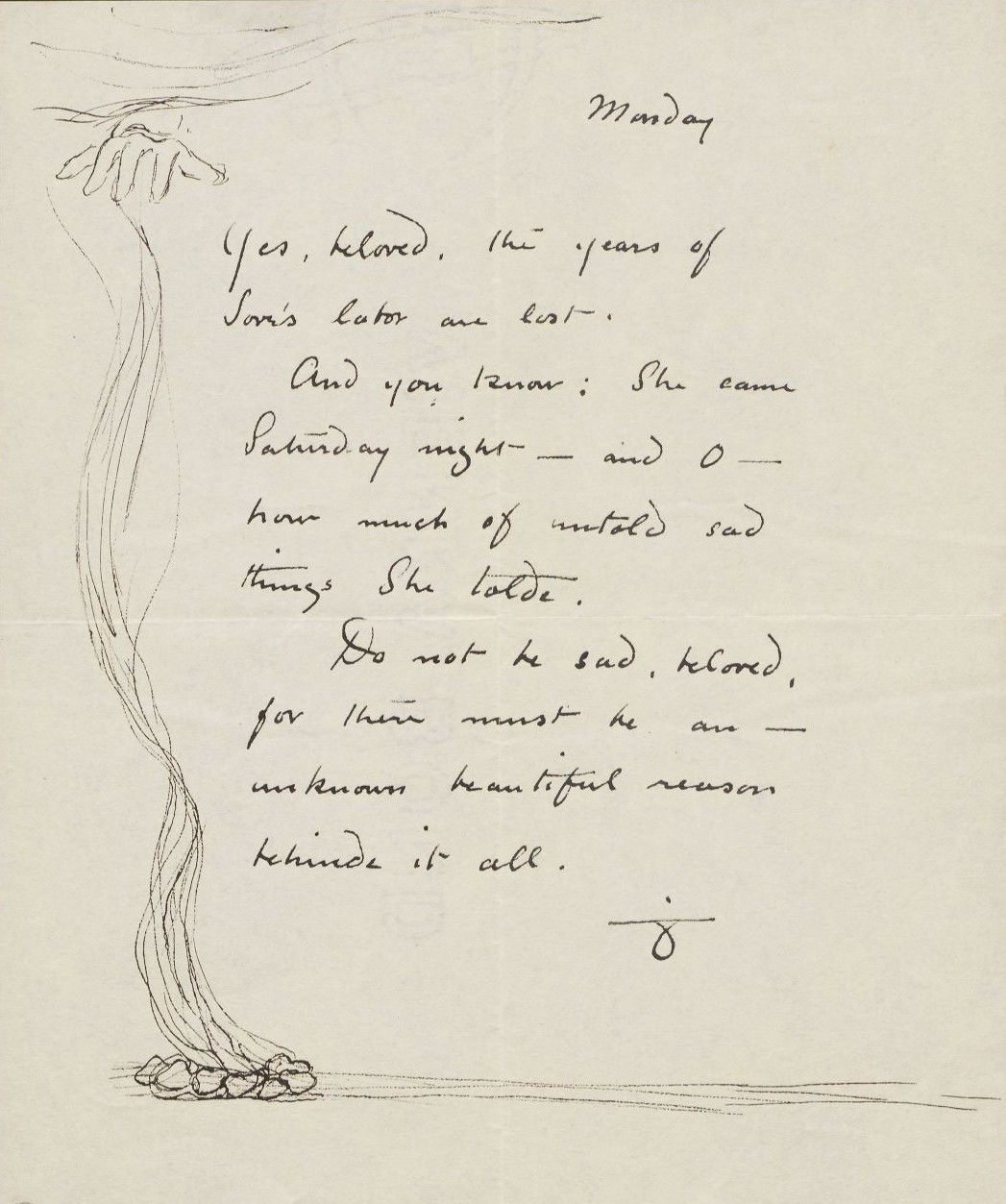

Unfortunately Gibran’s whole portfolio, that was in the studio of his early patron photographer and publisher Day, was destroyed. After an initial understandable disheartenment, the 21-year-old artist bore bravely the shock of the tragic event, to the point that he himself had to console his closest friends, all deeply upset by his loss. For example, in a 14 November 1904 note to poet and dramatist Josephine Peabody (1874-1922), he wrote: “Yes, beloved, the years of Love’s labor are lost. […] Do not be sad, beloved, for there must be an unknown beautiful reason behind it all.”[2] To the left of the message he made a sketch of smoke rising from coals and a hand, palm down, appearing out of a cloud to receive the smoke.

Probably we will never know precisely which and how many of his paintings and drawings ended up in smoke, but thanks to a full-page article published in the Boston Sunday Post on 27 March of that year[3] we can learn some of the titles of those artworks and their descriptions, with commentaries by noted professor of art and author Charles Elliot Norton (1827-1908), and above all admire six reproductions of them:

Said article also offers – although adding sometimes some fanciful and picturesque details – a minute description of the promising artist and poet (whose name is wrongly given as «Kahlil Gabran»), Boston’s “Little Syria” and his studio at 35 Endinboro Street:

“Kahlil Gabran is a large-eyed, olive-skinned, black haired youth […] who was born among the cedars of Lebanon. He is the son of an Arab sheik and has been educated both in the ancient wisdom of the East and in the Christian teaching of the modern West, as it is exemplified in Beirut. He draws with the simplest sort of crayons, but little removed from black and white, but at what a wonderful distance is this difference! And he draws with an unearthly purity of conception and

imagination. […] If you wander into Edinboro Street you will find it a narrow, smelly thoroughfare, with here and there little Syrians sitting on the doorsteps. If you know where to go, that is, to Gabran’s home, you will find yourself in an atmosphere that will surprise and amaze you. Up the stairs you go and into the little room. It is nude of all the things that generally go to make up an artist’s studio, but there is an atmosphere that truly reminds one of the times when artists worked, trying to make something for the good of mankind. In the room there are books that have been left him or given him by those who have in some one or another way found out his genius or that he has bought with an ever-unfailing taste for the good. There is Maeterlinck, Dante, Petrarch and many another old spiritualist dreamer, or what the average man is apt to call a dreamer, in the little bookcase that he has. And there is Barrett Wendell’s book on English composition. The subject of young Gabran’s chief work, that upon which he is now laboring, is, as nearly as it can be expressed in English, ‘The Souls of Men, Death and the Gods’.”

* This article is based on an excerpt from the paper “Tracing Gibran’s Footsteps: Unpublished and Rare Material,” in “Gibran in the 21th Century: Lebanon’s Message to the World,” edited by H. Zoghaib and M. Rihani, Beirut: Center for Lebanese Heritage, LAU, 2018, pp. 93-145.

[1] Cf. Harcourt Studios Destroyed: Fire Wrecks Building, Causing Loss of $200,000, Los Angeles Herald, No 42, 12 November 1904, p. 9: “Boston, Nov. 11. – The Harcourt studios, a two-story brick building in the Back Bay, was gutted by fire tonight, causing a loss of $200,000. The building was occupied by the Hutchins Votey Organ company. George H. Walker, publisher and lithographer, the Ranchard Machine company, the Pennsylvania Metal company and about thirty artists' studios. Many artists slept in the building and several who were asleep when the fire broke out were rescued by firemen.”

[2] Cf. Salim Mujais, Letters of Kahlil Gibran to Josephine Peabody, Beirut: Kutub, 2009, p. 184.

[3] Percy Dakyn, “Young Arab Artist of Boston, Whose Beautiful Creations are a Source of Wonder,” Boston Sunday Post, March 27, 1904, p. 29.

[4] The drawing is currently kept safe in the Telfair Museum, Savannah, Georgia, USA (gift of Mary Haskell Minis).