-

-

-

-

Search

-

-

0

-

Shopping Cart

xProducts:0Cart Empty

-

by Joseph Nahas

edited by Francesco Medici and Glen Kalem

One day, instead of eating our lunch at the restaurant, Gibran and I prepared our own sandwiches and walked over to Battery Park. There we saw a blind man sitting on a bench, running his fingers over a white page covered with dots protruding through embossing. The man’s lips moved as if he were whispering to himself, as his fingers moved over the white sheet. As we passed by the blind man, Gibran remarked, “Let’s sit on the adjoining bench, eat our sandwiches quietly while watching this man with ‘seeing fingers.’” We sat down eating, while our eyes were fixed on the blind man, watching the expressions on his face, smiling now, frowning then, as his fingers deftly moved over one line after another, page after page. Soon, the sandwiches were consumed and Gibran turned to me and whispered, “Believe me, the mind of this blind man is more perceptive than many normally visional persons whose eyes glare at the sun without blinking. Let us stop and have a few words with him before returning to work [at the office of Al-Mohajer (The Emigrant)].”

As we stood up, the blind man lifted his head and said, “Good afternoon, gentlemen, I trust that your lunch was satisfying. Am I wrong in thinking that one of you wishes to speak with me? You see, with the loss of my eyesight I was compensated with the blessing of oversensitivity in hearing. I heard you come by, sit on the adjoining bench – even heard you munch your sandwiches.” Gibran cleared his throat and said, “We tried to be as quiet as possible, being fascinated with witnessing the law of compensation at work! I, with my colleague, wish to compliment you on your amazing talent. Would you attribute some of it to ‘’extrasensory perception’?” The blind man replied, “I really don’t know if ESP in this case is a factor, but didn’t you mention the law of compensation? ... I am more inclined to believe it to be a factor in my case. Don’t you agree with me?”... Gibran replied, “I most certainly do.”

As we stood up, the blind man lifted his head and said, “Good afternoon, gentlemen, I trust that your lunch was satisfying. Am I wrong in thinking that one of you wishes to speak with me? You see, with the loss of my eyesight I was compensated with the blessing of oversensitivity in hearing. I heard you come by, sit on the adjoining bench – even heard you munch your sandwiches.” Gibran cleared his throat and said, “We tried to be as quiet as possible, being fascinated with witnessing the law of compensation at work! I, with my colleague, wish to compliment you on your amazing talent. Would you attribute some of it to ‘’extrasensory perception’?” The blind man replied, “I really don’t know if ESP in this case is a factor, but didn’t you mention the law of compensation? ... I am more inclined to believe it to be a factor in my case. Don’t you agree with me?”... Gibran replied, “I most certainly do.”

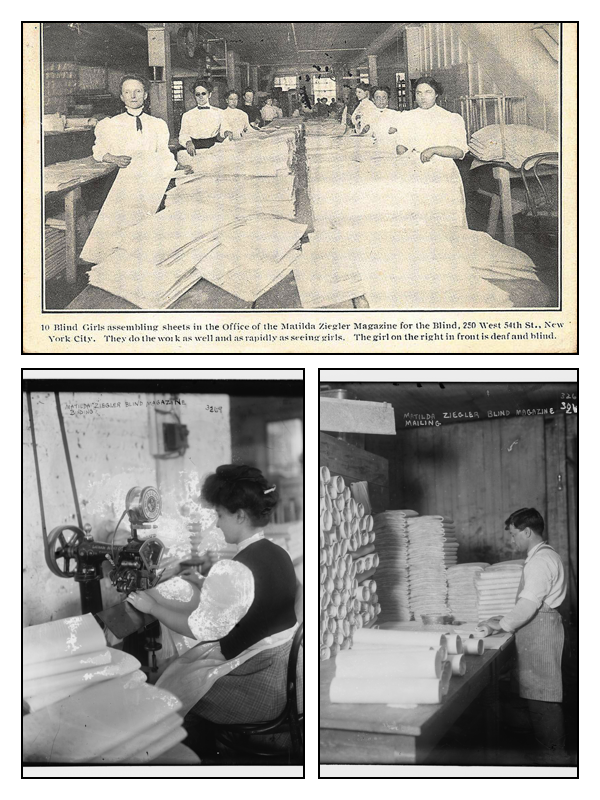

I then spoke, asking our blind friend what he was reading. He replied, “I am reading a magazine for the blind, issued by the Matilda Ziegler Magazine for the Blind, here in New York.” I looked at my wristwatch, saw it was time to be at work, and so indicated to Gibran, as I caught his eye. Gibran then said to our blind friend, “Sorry to deny ourselves the pleasurable privilege of visiting longer with you, but we must be back at work. We sincerely do hope to meet with you again.” The blind man said, “I understand, I understand.” Back at Al-Mohajer, Gibran said, “Wouldn’t it be interesting to see how that magazine for the blind operates?” I replied, “Why not plan on going there when time permits?”

That time came a few days later. We consulted the phone book for the address of the magazine, and boarded the Ninth Avenue elevated to 53rd Street, then to our destination. The offices and production area of the Matilda Ziegler Magazine were located on the second floor of the building, so we walked up the stairs and entered the office. As we entered the office, a comely young lady radiating smiles left her typewriter, walked up to us and said, “I am Bertie Anker. What can I do for you?” I was the first to reply by introducing Gibran, then myself, explaining that we both worked in a publishing house, that we met a sightless man reading “your” magazine, which aroused our curiosity. Gibran then added, “We wanted to see the work of the humanitarian agency which put sight into the fingertips of those whose eyes were denied by nature or accident the blessing of vision.” Miss Anker then introduced us to her sister, who was in charge of the office, then to a Mr. Kehoe, who was operating an oversize typewriter. This machine used very thin brass plates instead of paper sheets, and the keys had the regular letters of the alphabet as well as a combination of dots underneath each, representing the letter for which it stands. There was no typewriter ribbon. Mr. Kehoe explained that when a key is struck, it would automatically make the point indentation in the brass plate; thus words are embossed as you would type-print them on an ordinary sheet of paper. Every brass plate, he pointed out, is the same size as a magazine page. After the brass plates have been indented with the point system, they are sent to the production room for the embossing process.

Gibran remarked, “How wondrous is the law of compensation which works in diverse ways to offset some of the handicaps inflicted on the unfortunates... The cruel and greedy may be many, but the world will not be totally lost with the presence of people like these, dedicated to right the wrongs of circumstances and nature. Ministering to the needy and the handicapped is an assurance that we will not witness another fate as befell Sodom and Gomorah.”

Gibran remarked, “How wondrous is the law of compensation which works in diverse ways to offset some of the handicaps inflicted on the unfortunates... The cruel and greedy may be many, but the world will not be totally lost with the presence of people like these, dedicated to right the wrongs of circumstances and nature. Ministering to the needy and the handicapped is an assurance that we will not witness another fate as befell Sodom and Gomorah.”

Miss Anker then pointed to a girl using a regular typewriter, and said, “This is Henrietta Weiss, sister of the great magician Harry Houdini, whose real name is Weiss, same as his sisters’s.” Miss Weiss, looked up, blushed, and said, “Pleased to meet you.” She seemed to be shy; her glasses were exceedingly thick, indicating limited eyesight. Gibran whispered, “The dimness of sight was brushed aside by this courageous soul! Mark you, while history gives credit and glory to so-called heroes distinguishing themselves in wars of destruction, it is heroines such as this girl, that are the true workers in the fields of humanitism. They courageously go about, in spite of their handicaps, providing their own sustenance, while helping others in so doing.”

I asked Miss Anker if it were permissible to see how the magazine is “published.” She assured me that there was no objection, and that a Mr. Phillips, foreman of the production room, would be happy to show us around. She than used a phone near the production room door to call Mr. Phillips. He promptly came and, after introductions, she excused herself, returning to the office and her work. Mr. Phillips was of medium build, blond, slightly bald, and wore glasses. He seems delighted with our interest to see the production end of the operation, and took pains to explain the various steps in it.

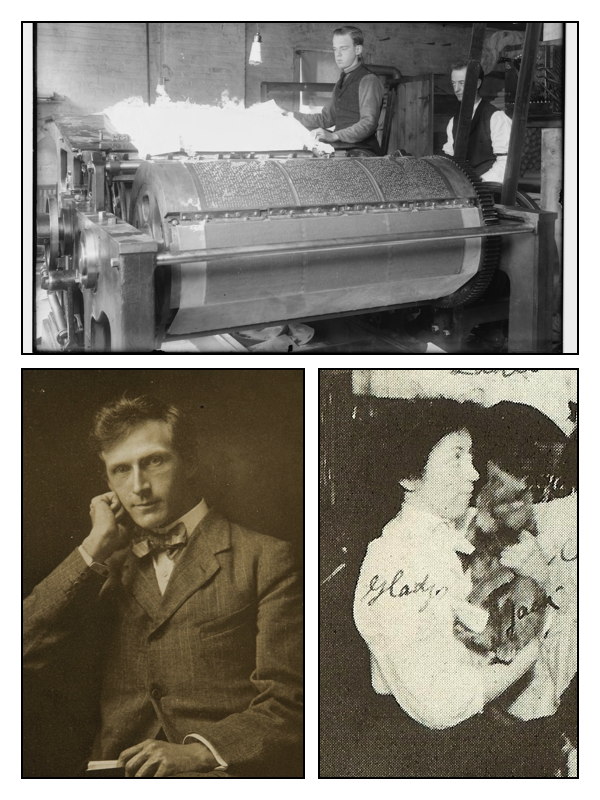

The first step, he said, is to prepare the stock (meaning the paper) for embossing by dampening it. The second step is to attach the indented brass sheets to the drum of the cylinder press. The third step is to feed the dampened paper sheets, as you would into any regular cylinder printing press.

The fourth step is to pick up the embossed sheets of paper and hang them on wires stretched along the bottom of three walls. The fifth step is to light the gas burners in the oven, shut its doors securely, and allow the paper sheets to “bake” – a sort of a hardening process. Phillips said that the magazine is “printed” in two types: one is called Braille; the second is known as the American Point System, which is a simplified form of Braille. Gibran told Phillips that while in Paris, he saw quite a number of blind persons reading magazines similar to the Matilda Ziegler Magazine, but never did he get the chance to see how they were produced. Feeling that we had taken up too much of Mr. Phillips’ time, we thanked him for his kind explanation, and proceeded to leave.

Reentering the office on our way out, we met the manager of the magazine establishment, Mr. Walter G. Holmes, who introduced us to a man standing by his side, a Mr. Anthony Fiala, explorer on the staff of Roald Amundsen, discoverer of the South Pole. Holmes was about the same height as Gibran, slender, but wiry, sporting well-groomed, mustachios – unlike those of Gibran, which drooped. Fiala was tall, lithe, and erect. We exchanged pleasantries and, as we were about to leave, Gibran, in a moderate tone of voice, addressed Holmes, saying, “During my art study in Paris, I had occasions to visit the cathedral of Notre Dame and, were I of a materialistic thought, and taste, I could have been fascinated with the material and artistic wealth it contained, but judged by spiritual and humanitarian standard of values, it is no better a temple to the Omniscient Creator than this unpretentious one of yours. There, they say, ‘It was erected for the glory of God’; here, your work is dedicated to His true glory, in exemplifying His love – His compassion.” Holmes was so pleased with Gibran’s comment and compliment that he repeatedly shook his hand vigorously.

Reentering the office on our way out, we met the manager of the magazine establishment, Mr. Walter G. Holmes, who introduced us to a man standing by his side, a Mr. Anthony Fiala, explorer on the staff of Roald Amundsen, discoverer of the South Pole. Holmes was about the same height as Gibran, slender, but wiry, sporting well-groomed, mustachios – unlike those of Gibran, which drooped. Fiala was tall, lithe, and erect. We exchanged pleasantries and, as we were about to leave, Gibran, in a moderate tone of voice, addressed Holmes, saying, “During my art study in Paris, I had occasions to visit the cathedral of Notre Dame and, were I of a materialistic thought, and taste, I could have been fascinated with the material and artistic wealth it contained, but judged by spiritual and humanitarian standard of values, it is no better a temple to the Omniscient Creator than this unpretentious one of yours. There, they say, ‘It was erected for the glory of God’; here, your work is dedicated to His true glory, in exemplifying His love – His compassion.” Holmes was so pleased with Gibran’s comment and compliment that he repeatedly shook his hand vigorously.

On the way back Gibran seemed very deep in thought until we almost ended our journey on the elevated train. He then looked at me and said, “We must explore it.” I asked, “Explore what?” He replied, “Such a help to blind readers in the Arabic language. What a blessing it would be for them to learn, and be able to read in Arabic, as the Matilda Ziegler Magazine offers in English.” I replied that for all we know, there could be such publications in existence, but if not, it should not be such an impossible task to convert the Arabic alphabet characters to such a point system as that of Braille.

By then the train had reached our station. We walked down to Battery Park, where we selected a bench and sat down to continue our conversation. Gibran asked, “Am I wrong in saying that you once said to have had worked on adapting the Arabic script alphabet for use on the Linotype?” “Not Linotype, but the Intertype,” I replied.

“What is the difference between the two?” Gibran asked. I proceeded to explain that both are typesetting machines, and that the Linotype was invented by a man named Mergenthaler, and that it was first on the market. I continued, saying that a Mr. Soper, superintendent of the Intertype plant located in Brooklyn Heights, came to see me at the publishing house, and asked if I would help them adapt the Arabic alphabet for use in conjunction with their machine, and I agreed that I would.

Najeeb Diab, publisher of an Arabic newspaper, Meraat-ul-Gharb (Mirror of the West), whose offices were located at 93 Washington Street, Manhattan, was kind enough to supply me with a full set of type to experiment with. When at last I thought my efforts were crowned with success, we discovered that another, Salim Sarkis, of Cairo, Egypt, had been working on a similar project, and that he had, by a matter of few days, applied for letters of patent. The Intertype people were satisfied with the improvement over the basic patent of Sarkis, and thanked me for my efforts with a remuneration check. Gibran commented, “It was a worthwhile effort – and you might supplement it by doing some research in the field of opening the blind eyes of Arabic readers by giving them a point reading system such as the Braille.”

Najeeb Diab, publisher of an Arabic newspaper, Meraat-ul-Gharb (Mirror of the West), whose offices were located at 93 Washington Street, Manhattan, was kind enough to supply me with a full set of type to experiment with. When at last I thought my efforts were crowned with success, we discovered that another, Salim Sarkis, of Cairo, Egypt, had been working on a similar project, and that he had, by a matter of few days, applied for letters of patent. The Intertype people were satisfied with the improvement over the basic patent of Sarkis, and thanked me for my efforts with a remuneration check. Gibran commented, “It was a worthwhile effort – and you might supplement it by doing some research in the field of opening the blind eyes of Arabic readers by giving them a point reading system such as the Braille.”

Soon after, we entered the First World War, and parted company, except for two or three occasional meetings after that war ended, and then I was neck-deep in the more lucrative industrial field.

(excerpt from: Joseph Nahas, “Seventy-Eight and Still Musing: Observations and Reflections. With Personal Reminiscences of Gibran as I Knew Him,” Hicksville, New York: Exposition Press, 1974, pp. 42-47)